Another in our series of new transcriptions of contemporary articles on the Leo Frank case.

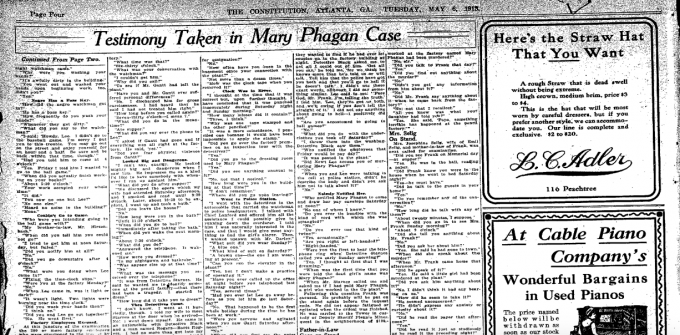

Atlanta Constitution

Tuesday, May 6th, 1913

Lemmie Quinn, Foreman of the Department in Which the Little Girl Worked, Was in His Office Just a Few Minutes After She Received Her Pay on the Day of the Murder, He Tells the Coroner’s Jury at Inquest on Monday Afternoon.

LEO FRANK INNOCENT NEW WITNESS TELLS ATLANTA DETECTIVES

Quinn Declares That Officers Accused Him of Being Bribed to Come to the Aid of Superintendent — Frank Is on Stand for Four Hours Answering Coroner’s Questions—Body of Mary Phagan Exhumed and Stomach Will Be Examined.

The Mary Phagan murder mystery assumed a new aspect yesterday afternoon, when Leo M. Frank, the suspected factory superintendent, introduced a third man in the baffling mystery, who the witness stated, called to see him after the girl had drawn her pay and departed.

Frank was testifying before the coroner’s inquest when he startled his audience with the declaration that he was visited by Lemmie Quinn, a pencil plant foreman, less than 10 minutes after the girl of the tragedy had entered the building Saturday.

Quinn immediately was summoned before Chief Lanford and Harry Scott, of the Pinkertons. He corroborated Frank’s story in detail. After being quizzed for an hour or more, he was permitted to return to his home at 31-B Pulliam street.

Foreman of Girls’ Department.

Quinn was foreman of the department in which the victim worked. He had known her ever since she first was employed with the concern. A stormy scene is said to have ensued during the interrogation to which he was subjected at headquarters. To a reporter for The Constitution, he last night declared that Scott and Solicitor Dorsey charged him with having accepted a bribe from Frank’s counsel for the story he was telling of the visit to the factory.

He says he retorted to the charge:

“Show me the man that says I took a bribe, and I’ll whip him on the spot.”

Quinn was seen last night by a reporter for The Constitution when he returned to his home from police headquarters. When asked if Frank’s statement were true, he said:

“Yes. It’s true. I left my house Saturday morning about 11:45 o’clock. On the way uptown, I stopped into Wolfsheimer’s and bought an order of fancy groceries. I stopped at another place and bought a cigar.

“Then I went to the factory. I wanted to see Frank and tell him ‘Howdy do.’ I knew he would be in the place. He is always there on Saturdays. It was about 12:15 or 12:20 when I arrived at the building. I saw no one in front or as I went upstairs to the office.

“Frank was at his desk. He appeared very busy. I stepped in and said: ‘Well, I see your work even on holidays. You can’t keep me from coming around the building on Saturdays either. How do you feel?’

“He said he was feeling good. He didn’t appear agitated or nervous. I didn’t want to disturb him, so I left. I wasn’t in the plant for more than 2 minutes. As I came downstairs on the way out, I saw someone in the rear of the first floor—a person whom I would have no grounds whatever to suspect.”

Won’t Tell Name Now.

“No! I won’t divulge his name. I’ll tell the detectives in time. I’m glad Frank told the coroner of my visit. It was I who refreshed his memory of the incident. He apparently had forgotten it. I have not been keeping it secret. I told the detective Saturday of the visit.

“I have known Mr. Frank for years, and I know he is not guilty.”

Frank’s story on the stand was to the effect that within ten minutes after Mary Phagan had departed with her pay envelope, Quinn, who is foreman of the tipping department, dropped into the superintendent’s office to say “Howdy do.”

“I had not thought of it until reminded of the incident,” he told the jury. “My memory was refreshed. I recollected it clearly. This is the first time I have made it known.”

The foreman, Frank stated, came into the building about 12:30 noon during Memorial day. “How do you do?” he is quoted with having said. “I see you work even on holidays. Well, you can’t keep me away from the factory on off days either.” He remained less than two minutes, according to Frank. IN BUILDING ONLY 2 MINUTES ……

Quinn declared to The Constitution that he was in the building about two minutes. He said that he did not see Mary Phagan.

He is outraged at the treatment he alleges was accorded him by the detectives.

“They were insulting and seemed to doubt my statement,” he said. “In an insinuating manner Chief Lanford plied the question: ‘So you put yourself there about the time the Phagan girl left the factory, eh?’”

Quinn was an ardent admirer of the murdered child. He says she was one of his most industrious employees.

He is married and has one child. His connection with the National Pencil company dates back to several years. The reporter met him at his home just as he was returning from the visit to police headquarters. He was fatigued, and admitted that he was almost exhausted.

Called on Frank in Jail.

Declaring that he had made his visit to Frank on Memorial day known earlier than Monday, Quinn told the reporter that it was he who refreshed Frank’s memory of his presence in the building shortly after noon of the day on which the girl is supposed to have been slain.

“I called upon Frank at the jail,” he said. “The moment I reminded him of my visit, he recollected it. He apparently had forgotten it.”

The foreman’s wife expressed dislike for her husband to be connected in the mystery. She seemed to regret that Quinn’s name had been mentioned at the inquest, merely because of the sensation it would incur.

“Now our name will be mixed in it, too,” she lamented.

Mother Thanked Foreman.

A day or so after her daughter’s tragic end, Mrs. J. W. Coleman called Quinn to her home on Lindsay street. She expressed the gratitude felt over the kindness and favors extended the dead girl by her foreman. Mary, she said, had often told her of how she liked Quinn, and of how pleasant it was to work under him.

When Quinn saw Mary’s step-father and her mother, he told the reporter, he expressed his belief in the superintendent’s innocence.

“I told them,” he said, “that with all the sympathy I felt for Mary and her relatives, I could not believe Frank guilty. I have worked for nearly four years under him, and I do not believe he was trying to shift the burden of suspicion by dragging my name into the case.

“He has told the truth. It is impossible for him to go against facts. He is purely a victim of circumstantial evidence. Time will tell the story. They may do me an injustice by bringing me into the scandal, but I am doing it in the defense of a guiltless man.

I believe the detectives are bungling this case. Lanford told me Monday that, inasmuch as I had not talked before, he guessed he would have to hold me. I retorted that I would not be the only innocent man he would be holding in that event.”

Body of Girl Is Exhumed.

Police headquarters and everyone concerned in the mystery were surprised Monday afternoon when it was learned that the body was exhumed in Marietta. The stomach has been placed in the charge of the state board of health and an analysis for traces of drug or “dope,” which it is suspected to contain, will be made.

The reinterment was witnessed by only the corner, Dr. John W. Hurt, country physician, and Dr. H. F. Harris, of the state board. Dr. Harris will perform the examination.

The inquest began fifty minutes later several days, it is stated. However, it is also said that Dr. Harris’ report will be prepared in time to submit it before the Thursday afternoon session of the coroner’s inquest.

The inquest began fifty minutes later than the time for which it was scheduled. This was due to Coroner Donehoo’s lateness in returning from the grave at Marietta. Police headquarters was thronged with a crowd of merely curious men, women and boys. Extra squads of police were necessary to handle the immense crowd.

FRANK FIRST WITNESS

Frank was the first witness. He was followed by his father and mother-in-law, Mr. and Mrs. Emil Selig, with whom he lives at 68 East Georgia avenue.

Factory Employees Are Excused.

About midway of the inquest, Coroner Donehoo excused the pencil factory employees who were waiting to be examined. They were released, however, subject to summons, and will be called back next Thursday. More than 200 of these witnesses appeared at police headquarters. A large majority were women and girls.

Frank and the negro, Newt Lee, were brought together from the Tower in Chief Beavers’ automobile. When they were ushered into the inquest room, the coroner ordered Lee returned to the Tower until he was called. Frank took the stand at 2:30. He was released at 6:15. No one but the coroner plied questions.

Leo Frank On Stand.

The first questions to Frank were the customary formal queries relating to his occupation, age and address.

His statement and the questions he answered are as follows:

“What is your connection with the pencil company?”

“General superintendent.”

“How long have you occupied that position?”

“Since 1908.”

“In what business were you prior to that time?”

“I was abroad, buying machinery for the National Pencil company.”

“Have you lived in Atlanta all your life?”

“No.”

“Where did you reside before moving here?”

“In Brooklyn, N. Y.”

“Were you ever married before?”

“No—only once.”

“What was your Brooklyn address?”

“152 Underhill avenue.”

His Work In Brooklyn

“What business were you in there?”

“I was with the National Meter company.”

“When did you leave Brooklyn?”

“In 1907.”

“What are your duties with the National Pencil company?”

“Look after the production and filling of orders and the purchase of machinery. In short, I have general supervision of the plant.”

“What time of the morning did you get up on April 26?”

“About 7 o’clock.”

“Was anyone with you beside your wife?”

“My mother and father-in-law.”

“Have you any children?”

“No.”

“Does anyone else live on the place at which you reside?”

“A negro washerwoman and servant.”

“What time did you leave the house on the morning of April 26?”

“Eight o’clock.”

“Who did you see?”

“Minola, the servant girl, and my wife.”

“Did you see Mr. and Mrs. Selig, your parents-in-law?”

“I don’t remember.”

“How did you leave the house?”

“Caught a trolley car. Got to the factory about 8:20, I presume.”

When He Reached Factory.

“Did you talk to anyone on the car?”

“I don’t remember.”

“Who was at the factory upon your arrival?”

“Hollway, the day watchman, and the office boy, Alonzo Mann.”

“Was the door locked?”

“No.”

“Who was in your office?”

“The office boy.”

“Did you see anyone else?”

“No.”

“How long was it before anyone came into your office?”

“About thirty minutes.”

“Who was it?”

“Several men for their pay envelopes.”

“Was Saturday, April 26, a whole or half holiday?”

“Whole holiday.”

“Were there others calling for their pay envelopes?”

“Yes. A girl named Mattie Smith came in shortly afterward.”

Frank Waited On Girl.

“Did you personally wait on them?”

“Yes.”

“Was there anyone else in the office?”

“Not that I knew of.”

“Who occupies the office with you?”

“The chief clerk, Herbert Schiff.”

“Was Schiff in the office at the time you paid Mattie Smith and those who preceded her?”

“No.”

“Who occupies the outer office adjoining yours?”

“The stenographer and office boy.”

“Was anyone in this office at the time?”

“Not that I knew of.”

“Who is your stenographer?”

“Miss Eubanks.”

“How long was it before anyone else came in?”

“Anywhere from a half hour to forty minutes. M. B. Darley, Wade Campbell and a Mr. Fullerton. They arrived about 9 o’clock.”

How Frank Spent Morning.

“Tell what you did during that part of the morning which followed 9 o’clock.”

“I went over the mail, business papers and later to the offices of the manager, Mr. Selig.”

“What time did you go there?”

“About 10 o’clock.”

“Did anyone go with you?”

“No. I went alone.”

“What did you do prior to 10 o’clock..

(This question was a repeater.)

“Various office duties, as I have already told.”

“Did you talk to anyone?”

“Yes. To Mr. Darley and Mr. Campbell.”

“Anyone else?”

“Not that I remember.”

“Did you touch the financial sheet of your concern?”

“No.”

“Can you recall anything else you did?”

“No.”

“Where did you say you went at 10 o’clock?”

“To the office of Sig Montag, the manager, at 20 Nelson street.”

“Do you remember the particular papers you handled?”

“Not exactly. A note, though, I recollect, was one ‘Rush Panama assortment boxes.’”

“What do you usually do in the morning?”

“Get up various papers over the desk and straighten out the work of my stenographer.”

“Did you speak to Hollway, the watchman?”

“Yes. But I only said ‘Good morning.’”

“Do you wear the same clothes at the factory which you wear at home?”

“Yes.”

“Did you remove your clothes when you reached the factory?”

“Only my coat. I exchanged it for one I wear at the office.”

No Personal Mail.

“Did you have any personal mail?”

“No.”

“Do you keep papers of value in the safe?”

“Yes.”

“Where is the safe?”

“In the outer office—the one adjoining my private office.”

“Can you recall the first paper you looked over?”

“No.”

“Who is your shipping clerk?”

“A Mr. Irby.”

“How long did you sit at your desk after your arrival in the morning?”

“I don’t know.”

“Did you intend going to the ball game?”

“Yes; until Saturday morning.”

“Did you work on the house order book?”

“Yes, but not until I got back from the office of the manager—No, I forgot. I did not work on it at all. Montag’s stenographer did it.”

“Who was in the office when you left for Montag’s?”

“Several persons—about six or eight in all.”

“How long were you at Montag’s?”

“Until 11 o’clock, I believe.”

“Did you telephone Miss Hall, Montag’s stenographer, that you wouldn’t need her at the pencil factory, and that she needn’t come?”

No, She Phoned Me.

“No. She telephoned me. I told her she need not come, as I did not need her.”

“When you departed for Montag’s, you’re sure you went alone?”

“Positive.”

“Didn’t Mr. Darley walk to Cruickshank’s at Alabama and Forsyth, to get a drink with you?”

“No. He did not.”

“Who was at the office when you returned?”

“Miss Hall, Montag’s stenographer, and the office boy.”

“How old is the office boy?”

“About 15 years, I presume.”

“Does he wear long or short trousers?”

“Short trousers.”

“What did you do upon returning?”

“Assorted papers and letters for about ten minutes.”

“What did you do while Miss Hall entered the orders you had given her, as you say?”

“I don’t remember, except that I was working at my desk.”

“Is your office work systematized?”

“Yes, excepting on times during which I have no special plans. Then, I take up the most important and pressing business.”

“What else did you do?”

“I don’t remember precisely. I was at work all morning and afternoon.”

“Were you out of the office at all while Miss Hall was in the building?”

“No.”

“How long was she occupied with the orders?”

“About thirty minutes.”

“When she finished the orders, what did you do with them?”

“I put them on my desk.”

“What time did she finish and leave?”

Miss Hall Leaves Factory.

“About 12 o’clock. I recollect the time, because I heard the noon whistle blowing. She and the office boy left together.”

“Did you see any outsider in the building when you got back from Montag’s?”

“No, I think not.”

“What did you do when the stenographer and office boy left?”

“Started to work on the orders.”

“Were you entirely alone?”

“So far as I knew.”

“Do you know of anyone else who came in?”

“Yes. A little after 12 o’clock the little girl that was killed came into my office.”

“Where were you?”

“At my desk in the inner office.”

“How did she announce herself?”

“I looked up when I heard her footsteps. I think she said she wanted her pay envelope. I asked her number, and she gave it to me. I gave her the envelope with her number stamped on it.”

“What was her number?”

“I don’t remember.”

“Have you ever looked up that number?”

“Yes, but I don’t recollect it.”

“When you gave her the pay envelope what did she do?”

Has the Metal Come Yet?

“Walked out into the outer office, stopped and called back: ‘Mr. Frank, has the metal come yet?’”

“Did you make entry of her payment?”

“No.”

“Did she call back about the metal as though in after thought?”

“Yes. It was natural. She hadn’t worked since Monday because of the lack of metal.”

“What was the amount in her envelope?”

“One dollar and twenty cents.”

“Do you remember in what denomination it was given her?”

“No. I don’t.”

“She disturbed you in your work, did she not?”

“Yes.”

“How did you know she was gone?”

“As she went down stairs I heard her footfalls dying away. I also heard another voice. It was vague, but like a girl’s or woman’s. It seemed as though it came from the Forsyth street entrance.”

“Did you know her name?”

“No.”

“Do you remember how she was dressed?”

“No. I only looked at her from over the side of my desk.”

“Was her dress dark or light?”

“What little I saw appeared light.”

“How was her hair arranged?”

“I don’t remember.”

Did Not See Them.

“How about the color of her shoes and stockings?”

“I didn’t see them.”

“Did you see a parasol, purse or handkerchief?”

“No. I didn’t notice.”

“How long did it take for you to give her the envelope?”

“About two minutes. Not longer.”

“How did you identify the number on her envelope?”

“She called it out.”

“Is that the only means of identification you employ?”

“Yes, except the name is written on the envelope, I think, I’m not sure.”

“Did you hear anyone else in the building at the time Mary Phagan was present?”

“Nothing but the voice downstairs as she went down the steps.”

“How long were you at the office after she had departed?”

“I stayed there.”

“Did anything else happen?”

“Yes; within five to ten minutes after the Phagan girl had left an employee named Lemmie Quinn, foreman of the tipping department, came into my office. He said: ‘I see you’re busy, but you can’t keep me away even on holidays.’ He stayed only a short time. This is the first time I recollected the incident.”

“What were you doing then?”

Where Did Quinn Go?

“Copying orders. It was about 12:35 o’clock, ten minutes after Mary Phagan had left.”

“Where did Quinn go?”

“I don’t know.”

“Had the metal come when Mary Phagan was in your office?”

“No. I don’t think it has come even yet.”

“How does it come to the plant?”

“By drayman.”

“Would you know if it had arrived?”

“Yes; I certainly would.”

“Where is it put—in what part of the building?”

“In the rear of the office floor.”

“Did you send Mary Phagan back to see if the metal had come?”

“No, I did not.”

“Now, tell the jury once more of Mary Phagan’s visit.”

(The witness was required to repeat the story of the girl’s appearance in his office at 12 o’clock to procure her pay envelope. The recital was without variance from the original statement.)

“How did you fix the time? You say it was about 5 minutes after 12?”

“It seemed that late.”

“Were you out of the office from the time the noon whistles blew until Quinn came in?”

“No.”

“How long had Mary Phagan worked at the pencil factory?”

“I don’t know; I really don’t.”

“Was she in Quinn’s department?”

“Yes.”

“Was she under him—was he her boss?”

“Yes.”

Was Not in Overalls.

“How was Quinn dressed?”

“I think he wore a straw hat?”

“Does he wear different clothes in the factory to what he wears at home and on the street?”

“I presume so. He was not in his overalls Saturday.”

“Has he access to the entire factory building?”

“Yes.”

“How old is he?”

“About twenty-five years, I would judge.”

“Is he married?”

“Yes.”

“How long has he been with the pencil company?”

“About four years, I understand.”

“What time did you finish work Saturday afternoon?”

“About 1 o’clock.”

“You are sure, now that you had not left the office from the time Miss Hall, the stenographer, had departed until you started away for lunch?”

Only Time I Left.

“I am positive. The only time I left was when I went upstairs to tell the two mechanics and the wife of one who were on the top floor, that I was ready to go and would have to lock up the building. I came back downstairs and picked up my coat.”

“How did you know they were upstairs?”

“The day watchman had told me.”

“How long did you stay there?”

“No longer than two minutes.”

“What time did you leave the place?”

“A trifle after 1 o’clock.”

“Doesn’t the day watchman usually stay at the plant until the arrival of the night watchman?”

“Yes, except on Saturday afternoons, when we close down for half holiday.”

“Do you know Walter Fry?”

“Yes. He’s a negro, the oldest employee in the factory.”

“Who pays him off?”

“The chief clerk, Mr. Schiff.”

“What did he do there Saturday?”

“I didn’t see him.”

Duties of Fry.

“Was Fry away from work upon your authority?”

“No.”

“What are his duties?”

“He sweeps and cleans glue from the floors on the glue room.”

“What time is he supposed to do this?”

“In the afternoons.”

“When you left the building, where did you go?”

“I went up Forsyth street to Alabama, up Alabama to Broad, where I caught a street car home.”

“Where did you get off?”

“At Georgia avenue on Washington street. I went directly home, arriving there about 1:20 o’clock.”

“How long were you at home?”

“Well, I ate dinner in about twenty minutes.”

“Was there any interruption to the meal?”

“No.”

“What did you do upon finishing?”

“I think I smoked a cigarette and lay down for a short nap.”

“What time did you wake?”

“I didn’t go good to sleep.”

“Have you been working strenuously?”

“I had been concentrating my mind on the work at the office. It was rather fatiguing, I’ll admit.”

“What time did you leave your home?”

“About 1:50 o’clock.”

“Where did you go?”

“To Washington street and Georgia avenue. I met a cousin, Jerome Michael, and talked with him until the 2 o’clock hour came.”

“Did you meet anyone whom you knew on the car?”

“Yes, another cousin, Cohen Loeb.”

“Where did you get off?”

“At the corner of Washington and Hunter street. The cars were blocked by the memorial parade.”

“Did you see anyone you knew?”

Watched Part of Parade.

“No. I walked to Hunter and Whitehall streets and watched part of the parade. Then, I walked to Rich’s store where I passed Miss Rebecca Carson, one of our foreladies. Then, I went to Brown and Allen’s, at the corner of Whitehall and Alabama streets and across to Jacob’s, where I bought four cigars and a pack of cigarettes.”

“Do you customarily smoke cigars or cigarettes?”

“Cigars, usually.”

“What did you do upon leaving Jacob’s?”

“Went straight to the pencil factory.”

“What time was it that you arrived there?”

“About 2:50 o’clock.”

“Did you unlock the door?”

“Yes. I unlocked the outer and inner doors, relocked the outer door and left the inner door open.”

“When you passed the clock in front of your office, what time was it?”

“I didn’t notice. It must have been about 3 o’clock. I pulled off my coat and went upstairs to tell the mechanics that I had returned. They already were preparing to leave.”

Then Mechanics Leave.

“How long was it before they came downstairs?”

“Only a few minutes. They entered my office about five minutes after 3 o’clock.”

“How long before you went downstairs?”

“Three minutes, or four—maybe five. I went down to lock the door.”

“You were left alone in the building?”

“So far as I knew.”

“What did you do?”

“Worked on the books.”

“When you went to lock the door, did you see the girl?”

“No.”

“How long did you work on the books?”

“Until about 4 o’clock, or 4:15. I had gone to wash my hands when the night watchman came.”

“Why were you washing your hands?”

“It’s awfully dirty in the building.”

“You went out and washed your hands upon beginning work, too, didn’t you?”

“Yes.”

Negro Has a Pass Key.

“How did the negro watchman get in?”

“He has a pass key.”

“How frequently do you wash your hands?”

“Whenever they get dirty.”

“What did you say to the watchman?”

“I said: ‘Howdy, Lee. I didn’t go to the baseball game. I’m sorry I put you to this trouble. You may go out on the street and enjoy yourself for an hour and a half. Be sure and be back within that time, though.”

“Had you told him to come at 4 o’clock?”

“Yes. Friday I told him I wanted to go to the ball game.”

“When did you actually finish working on your books?”

“About 5:30 o’clock.”

“Your work occupied your whole time.”

“It did.”

“You saw no one but Lee?”

“No one else.”

“Heard no noises in the building?”

“None.”

Couldn’t Go to Game.

“Who were you intending going to the ball game with?”

“My brother-in-law, Mr. Hirzenbach.”

“When did you tell him you could not go?”

“I tried to get him at noon Saturday, but failed.”

“Did you notify him at all?”

“No.”

“Did you go downstairs after 4 o’clock?”

“No.”

“What were you doing when Lee came in?”

“Fixing the time-clock slips.”

“Were you at the factory Monday?”

“No.”

“When Lee came in, was it light or dark?”

“It wasn’t light. Two lights were burning near the time clock.”

“Did you wash your hands then?”

“I think so.”

“Did you and Lee go out together?”

“No. He went first.”

Factory Employees Excused.

At this juncture of the examination the 200 or more factory employees who were summoned to the inquest by Coroner Donehoo were notified that they were excused for the day, but were subject to further summons. They had been sitting in the assembly hall. It was later than 4 o’clock when they left police headquarters.

“What time did he get downstairs?”

“Shortly after 6 o’clock.”

“Did you follow him?”

“Yes; I went downstairs to lock the door.”

“What did you see, if anything?”

“I saw Newt Lee talking to J. M. Gantt, a former employee of the pencil factory. Lee said: ‘Mr. Gantt wants to get his shoes.’ I asked him what shoes. Gantt said either black or tan, I forget which color. He saw that I didn’t like the idea of letting him in the building. He said, ‘You can go with me, or let the watchman go.’ ‘Lee can go,’ I told him. They went in together, Lee locking the door behind him.”

“What did you then do?”

“I went down Alabama street to Whitehall to Jacobs’ where I bought a drink and box of candy.”

“Did you talk with anyone there?”

“Yes. I held a short conversation with the young lady at the candy counter. Following that, I went directly home, arriving there about 6:35 o’clock.”

Went to His Home.

“Who was at home?”

“My father-in-law and Minola, the negro servant.”

“How long before your wife arrived?”

“She came about 6:30 o’clock.”

“Were you inside your home at the time she returned?”

“Yes.”

“What were you doing?”

“Telephoning.”

“Telephoning who?”

“The night watchman at the factory.”

“What time was that?”

“Six-thirty o’clock.”

“What was your conversation with the watchman?”

“I couldn’t get him.”

“Why did you call?”

“To see if Mr. Gantt had left the plant.”

“Have you and Mr. Gantt ever suffered personal differences?”

“No. I discharged him for gross carelessness. I had heard that he said I had not treated him right.”

“How long before you called again?”

“Seven-thirty o’clock—I mean 7.”

“What did you do in the meantime?”

“Ate supper.”

“What did you say over the phone to Lee?”

“I asked if Gantt had gone and if everything was all right at the factory. He said, ‘yes.’”

“Did you fear physical violence from Gantt?”

Looked Big and Dangerous.

“I can’t say, exactly. He looked mighty big and dangerous when I saw him. He impresses me as a kind I’d like to have somebody with whenever I run up against him.”

“What did you do after supper?”

“We discussed the opera which my wife had attended Saturday afternoon, and I smoked and read until 9:30 o’clock. Later, about 10:30 to be explicit, I went up and took a bath.”

“Did you leave the house?”

“No.”

“How long were you in the bath?”

“Until 11:30 o’clock.”

“When did you go to bed?”

“Immediately after taking the bath.”

“When did you wake the next morning?”

“About 7:30 o’clock.”

“What did you do?”

“Answered the telephone. It wakened me.”

“How were you dressed?”

“In my nightgown and bathrobe.”

“Was anyone else up at that time?”

“No.”

“What was the message you received over the telephone?”

“It was from Detective Starnes. He said he wanted me to identify someone at the pencil factory—that there had been a tragedy. I started to dress.”

“How long did it take you to dress?”

Then Detectives Come.

“I don’t know. I went at it hurriedly, though. I told my wife to meet Starnes at the door when he arrived—No! I went down myself. He came in an automobile with Detective Black and a man named Rogers—Boots Rogers. I had no more than got into my top shirt and sox when they arrived.”

“Who spoke first—you or they?”

“I don’t remember. I dressed and jumped into the machine. We went to Bloomfield’s, the undertaker, and I went in and saw the ‘poor little thing.’ I said: ‘That is the girl I paid off yesterday afternoon.”

“Describe her, will you?”

“She was bruised and cut about the face—a horrible sight. I saw a piece of wrapping cord around her throat and a strip of cloth.”

“In what department in the pencil factory is used the cord that was around her throat?”

“On the second floor for bundling pencils.”

“Is any used on the office floor?”

“Yes. Some.”

“How long were you at the undertakers?”

“Only a few minutes.”

“What did you do upon leaving?”

“Went immediately to the factory building.”

Went to the Basement.

“To which part of the building did you first go?”

“The basement with Mr. Darley, who arrived at the same time I did, and the detectives.”

“What time did you remove the tape from the watchman’s clock?”

“I don’t remember.”

“Did you examine the back door?”

“Yes, upon being told that it had been open.”

“Was it a part of the night watchman’s duty to go into the basement?”

“Yes.”

“How far was he supposed to go?”

“To the dust pan, which is situated only a few feet from the back door.”

“Were you aware that the building—or some parts of it—had been used for assignation?”

“No.”

“How often have you been in the basement since your connection with the plant?”

“Not more than a dozen times.”

“How was the clock tape when you removed it?”

Clock Was in Error.

“I thought at the time that it was correct but, upon further thought, I have concluded that it was punched inaccurately during Saturday night and Sunday morning.”

“How many misses did it contain?”

“Three, I think.”

“Why was one tape stamped and the other penciled?”

“It was a mere coincidence, I penciled one because it would have been impossible to apply the stamp.”

“Did you go over the factory premises on an inspection tour with the detectives?”

“Yes.”

“Did you go to the dressing room used by Mary Phagan?”

“Yes.”

“Did you see anything unusual in it?”

“No, not that I noticed.”

“How long were you in the building at that time?”

“I don’t remember.”

“Where did you go upon leaving?”

Went to Police Station.

“I went with the detectives in the automobile that carried the watchman to police headquarters. I talked with Chief Lanford and offered him all the assistance I could possibly give in running down the murderer. I told him I was naturally interested in the case, and that I would give most anything to find the girl’s slayer. Then, I walked uptown with Mr. Darley.”

“What suit did you wear Sunday?”

“A blue one.”

“What kind of suit on Saturday?”

“A brown one—the one I am wearing at present.”

“Can you run the elevator in the plant?”

“Yes, but I don’t make a practice of operating it.”

“Have you ever called up the office at night before you telephoned last Saturday night?”

“Yes, several times.”

“Had you ever let Lee go away before as you let him go last Saturday?”

“No. That happened to be the first whole holiday during the time he has been at work.”

“Were you nervous and agitated when you saw Gantt Saturday afternoon?”

“No.”

“When did you first see the notes found beside the dead girl’s body?”

About the Two Letters.

“In Chief Lanford’s office Tuesday, when Detective Starnes dictated them for me to copy.”

“When you began them, was the first letter a capital or small letter?”

“I don’t recollect.”

“Did you recognize the handwriting on the notes?”

“No.”

“Could you make out their composition?”

“No. Both were incoherent and illegible.”

“What was it in the dead girl’s appearance which caused you to recognize her body?”

“Her face.”

“How did you identify her as the girl to whom you gave the pay envelope last Saturday week?”

“I saw her plainly that day.”

“Wasn’t she badly bruised and cut about the face?”

“She was, badly.”

“How long have you had this blue suit which you wore Sunday?”

“Three or four months.”

“Did you ever wear it at the factory?”

“No.”

“Didn’t you tell Mr. Darley Sunday that you had on a new suit?”

“No. I merely remarked of the freshness of the suit I wore.”

“Did you change clothes Sunday morning?”

“Yes. I always change on Sundays.”

Conversation With Lee.

“How about the private conversation you had with Lee in the cell at police headquarters?”

“It was this way: The detectives asked me to talk to Lee. They said they wanted to find if he had ever let couples go in the factory building at night. Detective Black asked me to get all I could out of him. ‘Get all you can,’ he told me, ‘for we think he knows more than he’s told us or will tell. Tell him that the police have got you both and that you’ll go to hell if he doesn’t talk.’ I didn’t use those exact words, although I did say something similar. Lee said to me: ‘Fore God, Mr. Frank, I’m telling the truth.’ I told him, ‘Lee, they’ve got us both, and we’ll swing if you don’t tell the straight of it.’ I did not say anything about going to hell—I positively did not.”

“Are you accustomed to going to ball games?”

“No.”

“What did you do with the underclothes you took off Saturday?”

“I threw them into the washbag. Detective Black saw them.”

“Who notified the employees that Friday would be pay day?”

“It was posted in the plant.”

“Did Newt Lee accuse you of murdering Mary Phagan?”

“No.”

“When you and Lee were talking in the cell at police station, didn’t he describe the body and didn’t you ask him not to talk about it?”

“No.”

Nobody Notified Her.

“Who notified Mary Phagan to come and draw her pay envelope Saturday at noon?”

“No one of whom I know.”

“Do you ever tie bundles with the kind of cord with which she was strangled?”

“No.”

“Do you ever use that kind of twine?”

“Yes, occasionally.”

“Are you right or left-handed?”

“Right-handed.”

“Were you the first to hear the telephone ring when Detective Starnes called you early Sunday morning?”

“Yes. I thought at first that I was dreaming.”

“When was the first time that you were told the dead girl’s name was Mary Phagan?”

“When Mr. Starnes called me and asked me if I had paid Mary Phagan, a girl who worked in the tip plant.”

Following this question Frank was excused. He probably will be put on the stand again before the inquest ends. He did not appear fatigued or agitated when the ordeal was finished. He was carried to the Tower in custody of Deputy Sheriff Plennie Minerquest in the neighborhood of $100.-

Father-in-Law Goes on Stand.

Emil Selig, of 68 East Georgia avenue, father-in-law of the suspected superintendent, took the stand when it was deserted by Frank.

“How long has Leo Frank, your son-in-law, been married?”

“Three years.”

“Do you live with him?”

“No; he lives with me.”

“When did you first see him Saturday?”

“At dinner.”

“How long did he stay at dinner?”

“Quite a while.”

“When did you next see him?”

“At supper.”

“What did he first do upon arriving for supper?”

“Sat down at the table.”

“What did he do afterward?”

“Read in the hallway.”

“How long did you see him?”

“Until about 10 o’clock. Mr. and Mrs. Maurice Goldstein, my wife, Mrs. Ike Strauss, Mrs. Wolfsheimer and my daughter, Mrs. A. Marcus, were playing cards until 11 o’clock. Leo returned about 10 o’clock, I think.”

“Did Frank see these people?”

“I suppose he did.”

“How was he dressed?”

“In a brownish suit.”

“What time did you wake Sunday morning?”

“At 8 o’clock.”

Frank Called Up Factory.

“Did he often call up the factory upon coming home at night?”

“Yes.”

“Did Mrs. Frank tell you anything Sunday morning?”

“Yes. She said something terrible had happened.”

“Didn’t she say that a girl who worked at the factory named Mary Phagan had been murdered?”

“No, sir.”

“Did you talk to Frank that day?”

“Yes.”

“Did you find out anything about the murder?”

“No.”

“Didn’t you get any information from him about it?”

“No.”

“Did Mr. Frank say anything about it when he came back from the factory?”

“No; not that I recollect.”

“All you knew was what your daughter had told you?”

“Yes. She said, ‘Papa, something terrible has happened at the pencil factory.”

Mrs. Selig On Stand.

Mrs. Josephine Selig, wife of Emil Selig, and mother-in-law of Frank, was next called for examination.

“Did you see Frank on Memorial day—at supper?”

“Yes. He was in the hall, reading a paper.”

“Did Frank know you were in the house when he went to bed Saturday night?”

“Yes—he must have.”

“Did he talk to the guests in your home?”

“Yes.”

“Do you remember any of the conversation?”

“No.”

“How long did he talk with any of them?”

“About twenty minutes, I suppose.”

“When did you go in to see Mrs. Frank Sunday morning?”

“About 9 o’clock.”

“Did she tell you anything about Mr. Frank?”

“No.”

“Did you ask her about him?”

“Yes. She said he had gone to town.”

“When did she speak about the murder?”

“When Mr. Frank came home that afternoon.”

“Did he speak of it?”

“Yes. He said a little girl had been murdered at the plant.”

“Did you ask him anything about it?”

“No. I didn’t think it had any bearing on us.”

“How did he seem to take it?”

“He seemed unconcerned.”

“He didn’t express any anxiety or curiosity about it?”

“No.”

“Did he read the paper that afternoon?”

“Yes.”

“Did he read it just as studiously as he read it the preceding night?”

“Apparently so.”

“Did he seem to feel apprehensive?”

“No.”

“When did Frank first mention the name of the slain girl?”

“I don’t think I remember.”

The inquest was adjourned at 7:18 o’clock. It will be resumed at 9:30 Thursday morning. The two-days’ postponement is to permit detectives to garner evidence they announce available.

Following up a new theory advanced last night, detectives are said to have searched the roof of the National Pencil factory building in search of the victim’s missing pocketbook and pay-envelope, neither of which have ever been found.

Police headquarters could not verify the report at midnight. Two men with lanterns, however, were seen walking over the roof about 10 o’clock. They were noticed from The Constitution reportorial rooms. After remaining on the building for thirty minutes or longer, they disappeared through a scuttle hole.

* * *

Atlanta Constitution, May 6th 1913, “Third Man Brought into Phagan Mystery by Frank’s Evidence,” Leo Frank case newspaper article series (Original PDF)