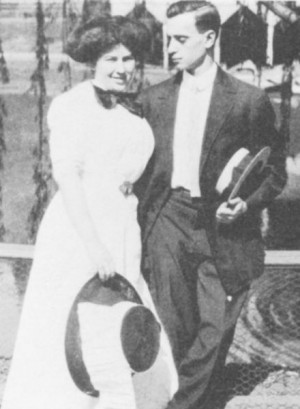

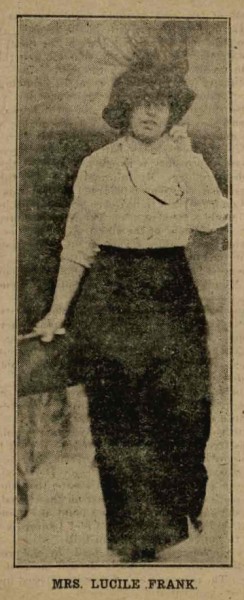

WHEN WE FIRST meet Lucille Selig Frank (pictured), she is attending the opera on April 26th, 1913 with her well-to-do friends and mother, Josephine — while, a few miles away, a young teenage girl lays freshly murdered in the factory directed by her husband, the soon-to-be-infamous Leo Max Frank.

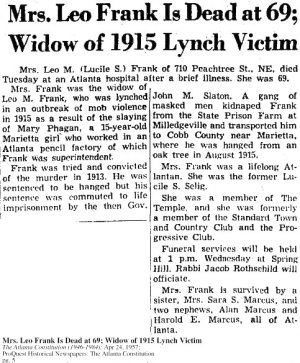

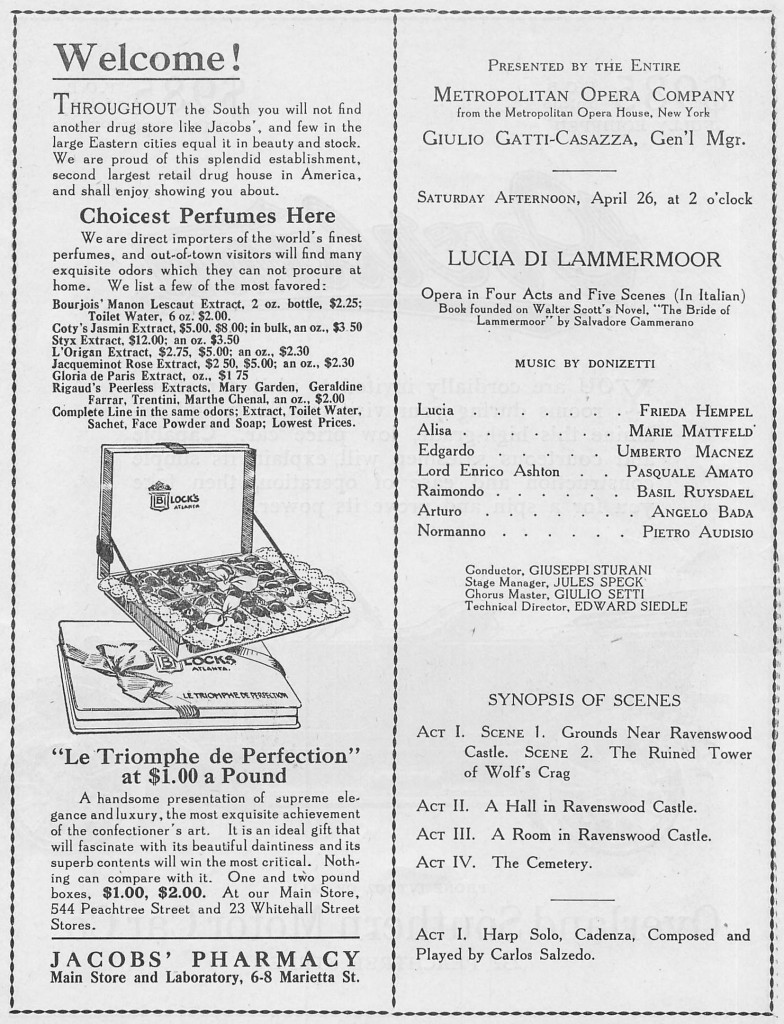

Below we see page 17 of the program for that Metropolitan Opera Company performance in Atlanta, Georgia, the very same as would have been held in Lucille’s hands that day. On the left side is an advertisement for Jacob’s Pharmacy, selling boxes of chocolates from France named Le Triomphe de Perfection.

Had there indeed been a perfect triumph that day? A coup de grace? A sex strangulation and plotted double murder in the making; one dead little Christian white girl, with one — or possibly two — African-Americans to be hanged for the crime? Or was the whole world about to turn upside down for Leo and Lucille?

As Professor Allen Koenigsberg puts it:

On Confederate Memorial Day, Saturday, April 26th, 1913, inside the palatial auditorium where the fourth annual season of the visiting New York City Metropolitan Grand Opera Company was coming to a close (NYC Metropolitan Grand Opera Programme, Atlanta, Georgia, April, 21 to 26, 1913), it was then and there, that fateful afternoon, at the last matinée of Lucia Di Lammermoor, where Frieda Hempel’s soulful voice was climbing hauntingly skyward, and while tears were showering down the eyes of Lucille Selig Frank, another script was playing out at a dingy four-story shuttered factory in the heart of downtown Atlanta. It was an event that would forever become an indelible part of U.S. legal history and mainstream popular culture. (The Leo Frank Case – open or closed?, 2013)

That evening, hours after the girl — Mary Phagan — was dead, Leo, in fact, stopped by that very same Jacob’s Pharmacy and so thoughtfully bought his wife a box of these “French” chocolates (see State’s Exhibit B, April 28th 1913). Was it a mere coincidence, and an act of loving affection? Did Leo Frank actually have a jealous quarrel with his wife on the morning of the murder, as later alleged by Albert McKnight? Was Leo Frank attempting to assuage his guilt for what might have happened at his National Pencil Company beginning at 12:02 PM?

April 26 and its Aftermath:

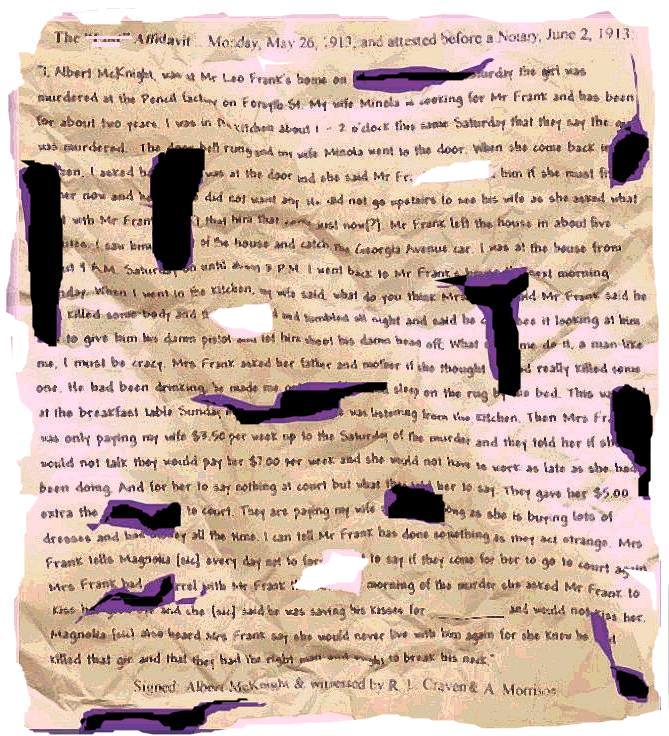

The affidavits by Minola McKnight, the Franks’ Negro servant, and Albert McKnight (Minola’s husband), leave us asking: What really happened at the Selig residence (the Franks lived with Lucille’s parents) on the morning, afternoon, and evening of Confederate Memorial Day, Saturday, April 26, 1913? (See Albert McKnight Affidavit, 1913 and State’s Exhibit J, June 3rd 1913.) Did Leo Frank buy those chocolates to help renew the favor of his wife in a troubled marriage — a wife whose support he would soon need? Did the Franks offer money and gifts to Minola in return for silence on certain matters? Did Leo Frank ask for a gun in order to shoot himself because he had just killed a girl? Did Lucille say to her husband that she “would never live with him again”?

Meet the Parents of Lucille Selig (Mrs. Leo M. Frank): a “Match Made in Heaven”?

Emil Selig and Josephine Cohen: In a coincidence of fate, both of Lucille’s parents were born on the same day and month, June 10th, but 13 years apart. Emil and Josephine had three daughters, Sarah Selig Marcus (1883 – 1957), Rosalind Selig Ursenbach (1884 – 1938), and Lucille Selig Frank (1888 – 1957).

Lucille Selig, an Atlanta native, was born in February of 1888, the youngest of three daughters, and her eldest sister was the only member of her immediate family bearing children. Sarah Selig Marcus and her German-Jewish immigrant husband Alexander E. Marcus (1873 – 1926) had two children, Harold and Alan, who, interestingly enough, years later revealed that Lucille wanted to be cremated and have her ashes spread at a park in Atlanta. Rosalind, who was married to Charles Ursenbach, a Christian Gentile, had a date with Leo Frank to see the baseball game on Confederate Memorial Day, Saturday, April 26, 1913, in the early afternoon — but Leo Frank canceled the get-together at about 1:30 PM, before the game started, while seated in the dining room of the Selig residence. Leo Frank would later give two different reasons, at two separate times, as to why he canceled the appointment: 1) because he had too much work to do; and 2) because he was afraid of catching a cold due to the inclement weather.

Lucille’s Father: Emil

Lucille’s father Emil Selig (June 10, 1849 – March 30, 1914) was the oldest of the four sons of Samsohn Selig and Sara Loeb. Emil worked as a salesman for the West Disinfecting Co., a maker of soaps and industrial cleaning supplies. Before that, he was a liquor salesman. The modest two-story-plus-basement Selig residence, at 68 East Georgia Avenue, was not owned by Emil and Josephine, but rented. Emil died on March 30, 1914 without leaving a will, according to the records office in Atlanta (Koenigsberg, 2013). His widow and three married daughters were thus his heirs in the normal course of events. Emil Selig’s final resting place is in the Jewish section of historic Oakland Cemetery in Atlanta, Block 279, Lot 58, Grave 3. From the perspective of the viewer, his grave is located at the right-hand side of Josephine Cohen Selig, his beloved wife.

Lucille’s Mother: Josephine Cohen

Lucille’s mother was Mrs. Josephine Cohen Selig (June 10, 1862 – January 27, 1933), daughter of Jonas Loeb Cohen (1823 – 1885) and Regina Abraham Cohen (1839 – 1918). Lucille’s maternal grandfather, Levi Cohen, was a religious pioneer who helped found the first synagogue in Georgia. Josephine was like most married women of privilege from good families in the South; she was a pampered housewife with an African-American servant to help with the duties of the home. The Selig family home benefited from the employment of 20-year-old Magnolia “Minola” McKnight, who served as their daytime cook and maid for two years, from 1911 to 1913. Minola took care of the laundry, housecleaning, and cooking for the Seligs during her work days that usually began at 6:30 AM and ended at 6:30 PM, allowing Josephine and Lucille more time for family matters, socializing, playing cards, attending cultural events, and enjoying Jewish society life. After her death in 1933, Josephine was buried next to her beloved husband Emil.

Marian J. Frank and Otto Stern Marry in Brooklyn

In New York City in January, 1910, Leo Frank’s little sister Marian J. Frank became Marian J. Stern, after marrying Otto Stern. Stern was a Jewish immigrant who had come from Germany in 1898 and became successful in the cigar business. Leo Frank, being older by a couple of years than his sister, naturally felt the underlying social pressures of the time — and knew he was long overdue to marry. But Leo already had his own marriage plans underway by 1910: He was fortunate enough to have been introduced to Miss Lucille Selig shortly after he had relocated to Atlanta in August of 1908; he began seriously courting Lucille in 1909 and by 1910 they were engaged to be married.

Marriage for Life: In 1910, the Cultural Norm

Marriage was a completely different concept in the early 20th century compared to what it is today. Life expectancy was shorter, and longstanding traditions from antiquity established deeply-ingrained social norms that ensured that most people remained married for life — even if the marriages were unhappy or simply failed. Marital problems were often either “worked through” or swept under the rug — but rarely did people officially end their marriages. The stigma of embarrassment and shame attached to divorce was all too real. There were divorces in the early 20th century, but they were very few and far between in comparison to recent years.

Happier times: 25-year-old Leo Frank, courting the 21-year-old Lucille Selig at Grant Park, Atlanta, Ga., July 17th, 1909. Exactly six years later to the day, while sleeping soundly on a prison dormitory cot at the State Penitentiary in Milledgeville, Georgia, Leo Frank would be “shanked” (one knife-thrust to his jugular) just before midnight. The weapon was a seven-inch butcher knife wielded by a fellow inmate, William Creen. Leo Frank barely survived the assault. One month later he was dead at the hands of a lynching party.

“Opposites Attract”: Miss Lucille Selig and Mr. Leo M. Frank

The marriage between Leo and Lucille appears to be more political and arranged than anything else. The marriage enabled an ambitious Leo Frank to position himself for ascending up through the ranks of Jewish social status and power in the New South.

If even a few of the allegations involving Frank’s sexual impropriety (that would come out at his trial and again afterward during appeals) — about what Frank was doing at the factory behind Lucille’s back — were true, then their marriage could not be described as happy by any stretch of the imagination. There was a veneer of happiness and proper social appearances, but under that veneer things were likely very different. Lucille was living inside the facade of a “fairytale marriage” with a husband who took her — and their marital vows — for granted, if the allegations of philandering turned out to be even partly true. But there are some clear indications she might have come to terms with these facts by 1954 — and perhaps years earlier. At least three years before she passed away.

Lucille Selig Frank (February, 1888 – April 23, 1957) was very much different from Leo Max Frank (1884 – 1915). Lucille “Lucy” Selig was part of the socially active and highly assimilated German-Jewish community of Georgia. Somewhat overweight, what she lacked in looks she made up for in personality. She was considered very much Southern and “sassy.” Despite being from a well-to-do and prominent Jewish family, she was very provincial compared to Leo Frank. In fact, as any New Yorker will tell you, and Leo Frank was a New Yorker, everyone from outside of “the city” is to some extent provincial and unsophisticated.

Leo Frank: an Atypical Man

On April 27th, 1913, at 29 years of age, Leo Frank was not the typical boring engineer or gruff, intellectual manager one might have expected of a man who worked long days and 60-hour weeks, tabulating accounting sheets and wearing the many hats required to successfully operate a factory.

Despite his spidery appearance, he was reasonably physically fit after years of tennis and basketball at Cornell (1902-1906). To assert that he needed help carrying a dead body, as Jim Conley stated, is reasonable. But to claim that he hadn’t the strength to strangle an unconscious thirteen-year-old girl with a rope, as some polemicists have argued, is absurd.

In September, 1912, Leo Frank became the president of the elite 500-member Gate City Lodge of the Jewish fraternal order B’nai B’rith. Leo Frank was not the “nebbish” or “Nervous Nelly” often conjured up in descriptions of him by his partisans and critics alike. He was an odd-looking man, but was not especially petite or weak.

Leo Frank was a confident leader and active socialite at college, afterwards serving in high-ranking positions in Southern Jewish society life. Moreover, Frank was quite the “man’s man”: one who drank, smoked, partied, and, if the allegations are true, enjoyed a bit of philandering on the side whenever he so desired — even on the Sabbath.

Leo Frank was cosmopolitan, well traveled, and, in addition to English, could speak basic German, Hebrew, and Yiddish. To top it all off, Frank was educated to be part of the elite of industrial leaders: the well educated Ivy-Leaguer of privilege who had more than just the opportunity to study at Cornell, one of the best schools in the United States — but who also, after college, took an educational “sabbatical” overseas, being trained in Germany for his future work as factory head and part-owner.

The Odd Couple: Leo and Lucille

The Odd Couple: Leo and Lucille

After her marriage, Lucille appeared to gain significant weight, perhaps due in no small part to the traditional Southern cooking of her family’s personal cook, Minola. Lucille was what the Yiddish-speakers of New York would call zaftig and what young people today might call “extra thick.” But she was said to wear her weight well for the most part, though her adoption of a very short haircut created an androgynous look. Her contemporary photos show a rather unflattering evolution before and during the Leo Frank trial, though in her much later years, long after Leo Frank’s death, she shed much of that weight — while, understandably, acquiring a hard, worn expression.

Some contemporary observers allege that Leo Frank got bored with Lucille early in the marriage. Frank’s factory was flooded with an ever-changing lineup of svelte former farm girls, working-class teenage child laborers who were blossoming much faster than their upper-class counterparts. These working class girls often matured physically ahead of their time, unlike the daughters of middle class and wealthy families, whose patriarchs could ensure their daughters wouldn’t have to give up school to work long hours in dingy mills and factories for a number of pennies an hour. Child laborers generally earned less than ten cents an hour during the early decades of the 20th century, some as little as one penny an hour.

Is Power the Ultimate Aphrodisiac?

Leo Frank’s critics emphasize his wily behavior and his attempts to sexually lure the young girls in his employ. But the reality was probably less one-sided than that, as any man in a position of status and rank can tell you: The law of power and attraction applies at all times and in all places — thus there was likely no shortage of willing participants in whatever sexual endeavors Leo Max Frank was inclined to explore.

Child Prostitution

And it was more than just the endless stream of poverty-stricken and blossoming, hormonal teenage girls funneling into the factory each day that provided inspiration. A simple phone call to Leo’s favorite madam, Nina Formby, could bring any number of illicit delights. Formby was a mamasan running a child brothel in Atlanta’s Red Light District on Mechanic Street, which was conveniently located only a few blocks north of Frank’s National Pencil Company factory. It is a sad fact of life that Frank, seated at the helm of his company, could order the new “catch of the day” whenever he so desired and have young teen and even pre-teen prostitutes delivered by foot to his office for lunch, or after work, or on Saturdays, and no one would notice any difference, since the factory was always brimming with young girls coming to and fro. Many of the girls who ended up in the child brothels of Atlanta had been former child laborers ground down in the industrial factories and mills of which the National Pencil Company was one. Some of these girls — like Daisy Hopkins, who was a former National Pencil Company employee — might have made that lifestyle decision by choice alone, but we may be sure a large number were entirely victims, and at a tragically early age. Prostitution of all kinds, including the White slave trade was an unfortunate part of the growing pains of late 19th century and early 20th century Atlanta, with politicians on the take, often looking the other way. Cosmetic efforts were often made to stem the tide of this illicit trade and its decline would not come until severe criminal penalties were put in place by the government.

Pioneering Family

The Seligs were a notable family that had historically helped to establish religious culture for Southern Jewry. A pioneering member of the family created a successful chemical company (see below).

Mr. Simon Selig was the nephew of Emil and founded the Selig Chemical Company that later became one of the premier businesses in Atlanta involved in the “manufacture and sale of home-cleaning products (soaps, dispensers, disinfectants, and other cleaning agents), insecticides, and other consumer goods” (Pioneer Neon Supply Co., Artery web site, accessed 2012).

A Southern Belle Named Lucille Selig

Lucille was educated in Atlanta’s public school system. Lucille did not attend college once her education ended with the completion of high school (c. 1906), which was quite normal for both men and women of the period, especially women. It was not until the latter half of the 20th century that female enrollment at the university level surged upward.

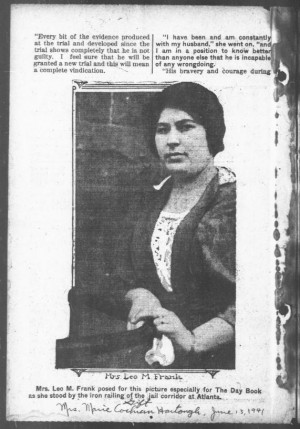

Leo Frank’s Defenders On the Image of Lucille Selig:

Leo Frank partisans sometimes paint a two-dimensional picture of Lucille, portraying her as a woman who believed in the innocence of her husband from the inception of his travails — and until the end of her life. Lucille did become vocally indignant — throwing a tantrum and bursting into tears — when the prosecutor, Hugh Dorsey, insinuated at trial that her husband was philandering at the factory. At least publicly she refused to believe it. But something very unusual happened later to suggest she may have known the uncomfortable truth and wasn’t the oblivious housewife after all. Lucille was, without dispute, a fiercely loyal wife when all is said and done; and she might have been provincial — but she was not a naive Stepford wife.

There may have been a time, early on, when Lucille entirely refused to believe the accusations concerning Leo Frank’s marital unfaithfulness, although even that is far from certain: Her loyalty may have been more tribally- and practically-based than it was founded on a personal conviction of the heart. Whatever her former beliefs, 21st-century research has uncovered indications of her true attitude in her will of 1954, indicating her wish to be cremated, and her subsequent verbal instructions for the dispersal of her ashes — which specified that her remains not be interred next to Leo Frank’s.

The Notarized Last Will and Testament of Lucille Selig Frank Acquired

In 1954, three years before Lucille passed away, something very profound and emotionally liberating occurred that would forever be remembered as a defining moment in the life of this martyred figure. An unofficial document in the hands of Lucille was made legal and official. It was signed ‘Lucille S. Frank’, witnessed, notarized, and registered with the local government of Atlanta, Georgia — and that document from 1954 has survived to the early 21st century.

Unmistakable Implications

In Lucille’s short ‘Last Will and Testament’ notarized, registered, and currently present (2013) within the local government registry office of Atlanta, Lucille disbursed a number of her personal items — a few of which seem conspicuously absent from the list — to friends and family, but more importantly she specifically requested cremation. (Mrs. Lucille S. Frank, Signatory, The Last Will and Testament of Lucille Selig Frank, 1954, accessed 2012). What happened to Lucille and Leo’s wedding album? What happened to Leo’s wedding ring that he bequeathed to her during the last moments of his life?

From the perspective of the Jewish community, Lucille’s quiet yet controversial 1957 cremation was rather unusual. For a faithful, proud, and practicing Jewish woman from a prominent and historically significant Jewish family to go against the traditional practice of burial next to one’s deceased spouse — or at the very least requesting to have her ashes buried or spread near her husband — was distinctly odd.

Were her wishes, thus expressed, an honest and candid verdict against the innocence of Leo Frank? The very clear living request she gave to her family before she died (see statement of A. Marcus, Features, Oney, 2004), specifically asking them to spread her ashes in a local Atlanta park, meant clearly that Lucille did not want her ashes spread at the Mount Carmel Cemetery near her husband, hundreds of miles away, or buried there next to him. Did Lucille’s wishes speak volumes? Is Lucille even today speaking to us as the only jurywoman worthy enough to pass judgment, in a not-so-silent ballot?

The End of the Dog and Pony Show:

Widowed in 1915, Lucille Selig Frank was no ordinary “jurist peer” called to pass impartial judgment. She was much more intimate than that: She was the truly loyal wife of Leo Frank, a woman who stood by her husband unshakably and without absence through the whole humiliating ordeal, beginning two weeks after his arrest, including all his court appearances, and through every twist and turn of the defense’s strategy from 1913 to 1915 and beyond. That she could wish her remains to be placed far, far away from those of her late husband is a powerfully moving act. (It took Lucille two weeks to begin her stalwart defense of Leo, during which time she refused to even visit him in jail. Could this be a sign of the deep emotional turmoil his acts of infidelity and violence had caused?)

Lucille might not have known all the details about what happened at the National Pencil Company after twelve noon on April 26, 1913, but — if the June 3, 1913 affidavit of Magnolia McKnight, known as State’s Exhibit J, and the corroborating affidavit of Minola’s husband Albert, can be believed — she probably knew that Leo Frank had tried to seduce young Mary Phagan and had then killed her to protect his status and reputation. Imagine the magnitude of suppressed pain, grief, and suffering Lucille endured after learning from Leo’s own lips what really happened that fateful noon hour while she was at the Opera House. Imagine what it was like for the rest of her life having to publicly pretend otherwise. It’s certainly not a burden most people could fathom, much less endure.

Lucille was also very much involved in Leo Frank’s appeals. After his trial ended with a guilty verdict, another little girl came forward who claimed that Leo Frank had raped her, causing her to became pregnant; this little girl reported that after Leo Frank seduced her, he descended between her legs and sadistically plunged his teeth into the tenderest tissues adjacent to her vagina (Leo Frank Georgia Supreme Court Records, 1913, 1914). The child was permanently scarified, not just physically, but mentally. She and Leo’s alleged child were whisked way to a Christian home in Ohio for unwed teen mothers, which was the normal course of events in those times and circumstances. There can be no denying that such revelations were impossible for Lucille to miss or ignore: She acted as stenographer and secretary for her husband, managing and organizing his appeals petitions between 1913 and 1915.

One Theory: Leo Frank’s Guilt Does Not Require Mary Phagan’s Innocence

Recently, some researchers have entertained the hitherto unthinkable possibility that Mary Phagan was willingly engaging in a tryst or series of trysts with Leo Frank before she was killed. Could this idea have occurred to Lucille and her circle of friends, and could it have figured in her attitude toward her husband and his defense?

If we accept Leo Frank’s guilt, as an increasing number of 21st century scholars do, Frank either coaxed Mary Phagan into the factory’s metal room — or together Leo and Mary had established a pre-planned meeting in the metal room at noon. Was there an affair between them? In 1913, both the prosecution and defense closed off that possible permutation. Such a controversial theory was culturally unthinkable for most people in 1913 Atlanta: a church-going 13-year-old girl in a Christian conservative society having an affair with a married Jewish man; even though, back in those days, girls were permitted to marry at 15, and such was not uncommon — as census records reveal (see: www.ancestry.com).

Though not proven, we can now finally entertain the theory that Mary Phagan had planned to meet for a tryst with Leo Frank — one that took a turn for the worse in the metal room. But why? It seems unlikely that Leo Frank had a prearranged meeting with a completely different girl that day (Jim Conley says Leo asked him to be a lookout) and would then assault Mary Phagan, when Frank was expected to go to lunch and then a ball game that day in the afternoon with his brother-in-law Charles Ursenbach.

In the prosecution’s 1913 theory of the case, it is obvious why Leo Frank had to kill Mary Phagan — to silence her and prevent her from telling the authorities and her family members what happened in the metal room. But why would Leo Frank kill Mary Phagan if they had a prearranged assignation? According to researcher Gail Gleason’s sub-variation of the prearranged assignation permutation, Mary Phagan might have backed out or changed her mind — causing Leo Frank, a man who could not take no for an answer, to possibly lash out violently (Gail Gleason, Leo Frank Case Yahoo Discussion Group, 2012). Or, I might ask, did Leo Frank insist on sex, when Mary’s interests had not gone so far? In Frank case scholar Allen Koenigsberg’s variation of the prearranged meeting theory there is a wide array of speculation: Was Mary pregnant? Did she want out of the relationship? Did she extort money or favors from Leo Frank? Had she threatened to tell his wife Lucille? (Koenigsberg, 2013). As we travel back down the time web of the imagination to 1913 Atlanta, we must be fearless. We must not quail at the idea that Frank is guilty, as do some Jewish interest groups — nor at the idea that Mary Phagan may have had an interest in her boss, as many Christian conservatives and Southerners consider unthinkable. What seems certain to me is that Lucille Frank considered all these possibilities.

After his death, Leo Frank was embalmed and returned in a pine box by train to Manhattan’s Penn Station and then by hearse to his family home at 152 Underhill Avenue, Brooklyn, NY, for a final open black casket service. His grave may be found at Mount Carmel Cemetery, Section 1, 83-45 Cypress Hills Street, Glendale NY 11385.

Lucille returned to Atlanta after her painful and cathartic sojourn to Brooklyn. In Georgia she was for a time part-owner of a dress shop and became sporadically active in the work of the Temple and other Jewish philanthropic institutions. Lucille Frank, perhaps in part due to her harrowing involvement in this grisly case, never remarried. She died at the age of 69 of heart disease, which one observer called “a metaphor for a broken heart, the heart of a woman who once genuinely loved her husband and may have still felt love for him when she died.” In the later years of her life, her weight management issues seemed to disappear, as one photo clearly shows. Perhaps her weight problems were related to a painfully dysfunctional marriage and, under the surface, Lucille had always been a beautiful woman in spirit.

Difficult Choices

Wives and Mothers

We can not hold a “black or white,” right or wrong, lens up to loyal mothers and wives who stand by their sons and husbands; we cannot judge them as though in a court of law. We must see what Lucille S. Frank did in the context of familial and Jewish group loyalty — and that is a context of subtle shades and variations of gray. The Leo Frank Case is very much about reading between the lines. Even if, deep down, such women know of their loved one’s guilt, their acts cannot be condemned. Lucille did what she had to do.

Even though cosmetically she had to put on the mask of pretense and appearance — pretending publicly her husband Leo Frank was not guilty of the murder, or of any infidelities — on some level it was probably difficult for Lucille to trick herself into not believing the nineteen employees who came forward and suggested Frank was a sexual predator and pedophile who engaged in numerous illicit assignations and who tacitly facilitated the assignations of others. Some witnesses stated Leo Frank was regularly whoring on the Sabbath and trying to “turnout” many young girls at the factory. If Lucille and Leo had an unsatisfying or almost nonexistent sex life, she knew of it, even if no one else did — and, if so, she probably suspected what happened on those days when her husband was “working late” at his factory or “working late on the weekends”.

Leo and Lucille Frank never had children and, except for one unsubstantiated rumor, there was no hint of any pregnancy. As 21st century dispassionate explorers we might speculate: Was she naturally sterile, or was Leo no longer interested, or both? If the rumors were true about Leo Frank seeking out daliances with Atlanta’s prostitutes, in an age where there were no antibiotics, could he have given his once-virgin wife one of the many commonly known STDs or the silent sterilizer Chlamydia? And surely what was most shaming is that there was evidence discovered in 1914, during Frank’s appeals, that he inseminated one of his former factory child laborers, a naive young teen who became pregnant and was shipped off to a home for unwed mothers in Ohio, something that — no matter how much she repressed it — would have mortified Lucille.

Atmosphere of Permissiveness?

When a distraught Mr. Coleman went to the Bijou Theater on the fateful evening of April 26, 1913, desperately looking for his missing 13-year-old stepdaughter Mary Phagan, he stumbled upon National Pencil Company foreman Mr. N.V. Darley with Opie Dickerson, a teenage girl who worked at the factory. Their presence suggests an important question: What was an older married man with children, a high official at the factory and Leo Frank’s friend and associate, doing entertaining a young girl at the movies on a Saturday night? It added to the sense that there was a culture of social and sexual permissiveness at the National Pencil Company that by 1913 standards — and even by our own — was highly unacceptable.

An Unbearably Heavy Burden

What made Lucille a truly amazing wife is that she still stood by her husband during the whole ordeal, despite the embarrassing scandal and collateral damage to the National Pencil Company, the Selig Family, her friends, the B’nai B’rith, the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation, and the Jewish community as a whole. An intense focal point of shame caused by the notoriety of such a heinous murder was put indirectly upon Lucille. The accusation that a pattern of sexual harassment, and finally rape, preceded the strangulation of thirteen-year-old Mary Phagan must have affected Lucille deeply, whatever she believed in her heart about it, as did the evidence presented at the trial portraying Frank as a sexually aggressive rake “testing the waters” to see which girls in his employ might potentially be willing to engage in “extracurricular activities.” Also no doubt hurtful were the reports from the factory’s roustabout, Jim Conley, that Leo Frank was regularly cheating on his wife at the factory with Atlantan prostitutes on various Saturdays — and Conley’s recounting of two incidents in which he accidentally walked in on Leo Frank engaging in oral sex with two different Atlanta prostitutes at two different times.

All of this was a great deal to bear for Lucille — it would have been impossible for a lesser woman — despite the support she received from her family, friends, and associates.

The 1913 Pregnancy and Miscarriage of Lucille Selig Frank

Both Steve Oney (October 7, 2003) and Elaine Marie Alpin (March, 2010) suggest Lucille Frank was pregnant in 1913 and later miscarried. Oney (2003), in an oblique reference, claims:

“Seven decades later, Katie Butler, a former factory employee in her 80s, would tell her physician that she and Lucille were both pregnant during the early winter of 1913, but that Lucille had suffered a miscarriage.” (p. 85).

Presuming conjugal visits were not permitted, Oney’s inclusion suggests Lucille miscarried about seven to eight months into her pregnancy, since we must presume Leo inseminated Lucy before he was arrested at 11:30 AM on Tuesday, April 29, 1913.

Presuming conjugal visits were permitted — a vanishingly unlikely presumption for those times — and regardless of how far Lucille was along, there is no real evidence to suggest the pregnancy claim is true. It cannot be independently verified by any reliable sources and none of the voluminous surviving correspondence between Lucille and Leo, or their associates, makes even the slightest hints or subtle suggestions of a pregnancy, or condolences over a miscarriage. The surviving correspondence between Leo Frank and others during his imprisonment until Monday, August 16, 1915, is a massive series of letters that spans more than two years, the bulk of which is archived and preserved at several different university and public Jewish historical collections from Ohio (the American Jewish Archives), Massachusetts (Brandeis University), to Georgia (several institutions).

The Two Week Gap

After Leo Frank’s arrest on Tuesday morning, April 29, 1913, at 11:30 AM — his last day of freedom — his wife Lucille delayed an inordinate amount of time before visiting him. Lucille Selig Frank did not visit him in jail until Monday, May 12, 1913 (The Frank Case, Atlanta Publishing Company, 1913). Leo Frank’s detractors cited this 13-day visitation lapse as proof that his wife knew he was less than totally innocent. After the controversial June 3rd, 1913, Minola McKnight affair unfolded, in which the Selig’s cook and maid, dropped an insider’s bombshell at the Atlanta police station — saying Frank confessed to Lucille and asked her for a gun with which to commit suicide — that suspicion approached higher certainty. (see: Brief of Evidence, Minola McKnight’s, State’s Exhibit J, June 3 1913 and Albert McKnight’s Affidavit in the Leo Frank Georgia Supreme Court records, 1913, 1914).

On August 18, 1913, between 2:15 PM and 6:00 PM, during Leo Frank’s statement to the Fulton County Superior Court, he would respond to this “dastardly” charge about why his wife did not visit him in the early weeks after the Mary Phagan murder investigation began. To paraphrase Frank, Lucille had to be physically restrained because she wanted so eagerly to be locked up with him in jail — but was ultimately deterred by Frank because he didn’t want her to be subjected to professional newspaper paparazzi. (Leo Frank’s Unsworn Trial Statement, Brief of Evidence, 1913). Leo Frank’s questionable response was borderline melodramatic and unconvincing, to his detractors, incredulous. For neutral observers Frank’s explanation was doubtful and cause for skepticism, it likely chipped away at Frank’s already waning credibility — because then or now, no determined couple in such circumstances, would be deterred by any phalanx of media photographers, no matter how galling, especially considering that Lucille showed no evidence of being camera-shy at any other time before or after his arrest.

The Stoic Wife was Human After All

Steve Oney Interviews Alan Marcus, Nephew of Lucille Selig

“I spent several hours up the road in St. Petersburg with Alan [Marcus] and Fanny Marcus, two Atlantans who’d retired to Florida. Alan was Lucille Frank’s nephew. He’d grown up at her knee and borne witness to the devastation that the lynching had wrought on her life and in the life of Atlanta’s Jewish community.

“Following Lucille’s death in 1957, her body was cremated. She wanted her ashes scattered in a public park, but an Atlanta ordinance forbade it. For the next six years, the ashes sat in a box at Patterson’s Funeral Home. One day, Alan received what for him was an upsetting call. The ashes needed to be disposed of. Alan didn’t know what to do.

“In the years since Lucille passed away, the Temple, the city’s reform synagogue, had been bombed [(October 12, 1958)]. This event had set Atlanta’s Jews on edge. It was no wonder that Alan [Marcus] didn’t want to attract scrutiny by conducting a public burial. For months, he carried Lucille’s remains around Atlanta in the trunk of his red Corvair. Early one morning in 1964, he and his brother drove downtown to Oakland Cemetery. There, under the cover of the gray dawn light, the two men buried this martyred figure in an unmarked plot between the headstones of her parents.” [emphasis added]

(Source: University of Georgia Features, Georgia Magazine, Steve Oney, March, 2004)

The Frank-Stern family plot where Leo Frank is buried in Mount Carmel Cemetery in New York City. The grave set aside there for Lucille Frank is empty.

In New York City, there is an empty grave site — number one in the Frank-Stern family plot, next to Leo Frank’s grave — that was set aside for Lucille Frank (confirmed by Mount Carmel Cemetery records, 2013), but she chose not to be buried there. This has been a subject quietly avoided by most Leo Frank partisans. The empty grave site reserved for Lucille speaks to us in lonely whispers — and the silence from most writers on this subject is deafening. To account for the empty grave, there was a ghoulishly undocumented rumor proposed that the reason Lucille’s ashes were not buried or spread next to Leo Frank’s remains is because the stillborn baby of Marian Frank was buried there circa 1911 — but the state law of New York and the rules of Mount Carmel Cemetery require documentation of all burials of any kind with no exceptions. It is doubtful these rules were waived. Furthermore, there is no known reference to this alleged burial in all the prolific correspondence and records of Leo or Lucille.

In 2013, when this author asked the staff of the Mount Carmel Cemetery if there was any documentation, proof, or knowledge of a child — or anyone at all — buried in grave site number one, located to the left of Leo Frank’s grave site (number two), they reported that there is no one buried there, not even a stillborn baby (Live interview, Mount Carmel Cemetery staff and review of cemetery records, 2013).

Is empty grave site number one a time-traveling echo of truth about Leo Frank from the unfortunate woman, who, by a tragic twist of destiny’s many paths, submitted to matrimony with a book-smart and intelligent man, but lacking in common sense, one possessed with a penchant for sexual immorality and pedophilia? Are we to presume that Lucille Selig, who helped Leo Frank prepare his appeals petitions, overlooked the document from a former teenage factory employee who, the girl said, Leo Frank seduced one year before he murdered Mary Phagan — a document which also stated that Leo Frank traumatized the girl after he plunged his teeth deep into the innermost flesh adjacent to her vagina? Did she overlook the testimony that Leo Frank was caught with another little girl in the woods by a police officer Mr. House? Did she believe the bribed retractions of numerous witnesses to his profligacy? If the retractions were in fact procured with money as these witnesses deposed, did she know of it? (see: Leo Frank Georgia Supreme Court Documents, 1913, 1914)

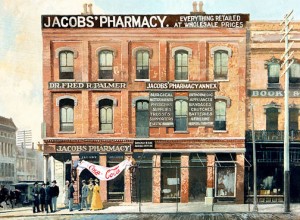

Lucille Selig Frank Obituary

Mrs. Leo Frank Is Dead at 69; Widow of 1915 Lynch Victim. The Atlanta Constitution (1946-1984); April 24, 1957; page 5.

“Lucille Selig Is Dead at 69; Widow of 1915 Lynch Victim Leo Frank”

Mrs. Leo M. (Lucile S.) Frank of 710 Peach Tree St., NE, died Tuesday, at an Atlanta hospital after a brief illness [(actually heart disease)]. She was 69. Mrs. Frank was the widow of Leo M. Frank, who was lynched in an outbreak of mob violence in 1915 as a result of the slaying of Mary Phagan, a 15-year-old [(actually 13 year old)] Marietta girl who worked in an Atlanta pencil factory of which Frank was superintendent.

Frank was tried and convicted of murder in 1913. He was sentenced to hang but his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment by then Governor John M. Slaton [(John Slaton was actually the law partner of Leo Frank’s lead trial attorney Luther Z. Rosser at the time)]. A gang of masked men kidnaped Frank from the State Prison Farm at Milledgeville and transported him to Cobb County near Marietta, where he was hanged from an oak tree in August 1915.

Mrs. Frank was a lifelong Atlantan. She was the former Lucile S. Selig.

She was a member of The Temple, and was she was formerly a member of the Standard Town and Country Club and the Progressive Club.

Funeral services will be held at 1:00 p.m. Wednesday at Spring Hill. Rabbi Jacob Rothschild will officiate.

Mrs. Frank is survived by a sister, Mrs. Sara S. Marcus, and two nephews, Alan Marcus and Harold E. Marcus of Atlanta.

Did Lucille Selig Die of a Broken Heart?

Did Lucille Selig Die of a Broken Heart?

Lucille Selig Frank died in 1957, just three short days before the 44th anniversary of the April 26, 1913 Mary Phagan bludgeoning, rape and strangulation — and Leo Frank’s likely murder confession to her on that night so long ago. There were certainly other dates equally significant, if not more so, for Lucille. One can imagine her wedding anniversary (November 30) likely elicited happy memories — and deep-seated emotional distress. Given the public notoriety and traumatic depths of the whole 120-week ordeal between the date of the arrest of her husband days after the murder and Friday, August 20, 1915 — the burial of Leo in Queens, NY — it was likely numerous anniversary dates every year were constant and painful reminders during the more than four decades of quiet suffering this unfortunate woman experienced. Let us hope that, when she made the decision not to be buried beside her husband, the spirit of Lucille Frank finally became free — free of the lies and legal wrangling, free of the deception and tricks, and free of the torment she so stoically endured for decades.

* * *

APPENDIX

References and further reading:

Information and background on the Leo Frank case:

The Leo Frank Case – open or closed? Professor Koenigsberg’s Leo Frank Discussion Group.

Thomas Watson’s historical analysis of the case

The American Mercury‘s Bradford Huie analyzes the Leo Frank case

100 Reasons Leo Frank Is Guilty

The Aborted Apotheosis of Leo Frank, part 1

The Aborted Apotheosis of Leo Frank, part 2

References:

Atlanta Journal Wedding Announcement of Leo Frank and Lucille Selig, December 1, 1910. Atlanta Journal, Thursday, December 1, 1910, Wedding Announcements Society Pages: https://leofrank.info/library/wedding-announcement/wedding-announcement-society-pages-atlanta-journal-thursday-december-1-1910.pdf

Professor Allen Koenigsberg, PhD, Brooklyn College, The Leo Frank Case Discussion Group, 2008+ http://groups.yahoo.com/group/LeoFrankCase/ (sign up required).

The Temple, Atlanta, Georgia. http://www.the-temple.org/

National Park Service of Atlanta, http://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/atlanta/text.htm. Accessed March 3, 2012.

Mount Carmel Cemetery (MCC), Grave Spot #1 (Official Real Estate location ID: 1-E-41-1035-01), Reserved for Lucille Selig Frank is empty, it is left of Leo M. Frank’s occupied Grave Spot #2 (Official Real Estate location ID: 1-E-41-1035-02). Staff office and records of the Mount Carmel Cemetery. Rachel Frank purchased the plot in 1911. No record of Marians still born child buried in the Frank-Stern plot, but the bench located at plot 7 is thought to be in remembrance for the deceased child. According to the administrator at MCC: Section 1, Block E, Path 41, Lot #1035, Grave #1 is empty based on official legal cemetery interment records, documented in writing on Cemetery letterhead.

The Notarized Last Will and Testament of Lucille Selig Frank (Signed Lucille S. Frank), Atlanta, GA, 1954, Records Archive.

And the Dead Shall Rise, by Steve Oney (recommended by the Leo Frank Research Library and Archive despite its errors, purchase on www.Amazon.com)

Georgia Magazine, ‘And the Dead Shall Rise’ by Steven Oney, (March 2004: Vol. 83, No. 2): https://leofrank.info/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/georgia-magazine-2004-and-the-dead-shall-rise-steve-oney.pdf

Emil Selig Memorial at “Find a Grave”: http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=32045801

Leo Frank Research Library and Archive Memorial for Lucille Selig Every Year:

Please light a candle every April 23, to remember Lucille Selig, this martyred figure, as Steven Oney described her.

Sleep dear Lucille Selig, sleep well, you will never be forgotten. Rest in Peace, dear soul…

Further Reading:

Pioneer Neon Company: http://www.artery.org/Selig-PioneerNeon.htm

The Selig Company Building – Pioneer Neon Company

National Register listed: 1996

Location: 330-346 Marietta Street, Atlanta, Fulton County, GA 30303

Pingback: The Biography of Leo Max Frank (Thursday, April 17, 1884 to Tuesday, August 17, 1915) and the Bludgeoning, Rape and Strangulation of Little Mary Anne Phagan on Saturday, April 26, 1913.

Pingback: 99 Years Ago: Did Leo Frank Confess? « National Vanguard