Another in our series of new transcriptions of contemporary articles on the Leo Frank case.

Atlanta Georgian

Thursday, May 29th, 1913

Swears Frank Told Him Girl Had Hit Her Head Against Something.

The Georgian in it second Extra published exclusively the first REAL confession of James Conley, the negro sweeper at the National Pencil Factory, regarding the part he played in the Mary Phagan mystery.

The Georgian has dealt in no haphazard guesses as to the negro Conley’s testimony to the police and in giving prominence to his statements desires to say that it must not be taken as final until it is examined at the trial of Frank.

Atlanta, Ga., April 29, 1913.

On Saturday, April 26, 1913, when I come back to the pencil factory with Mr. Frank I waited for him downstairs like he told me, and when he whistled for me I went up stairs and he asked me if I wanted to make some money right quick, and I told him yes, sir, and he told me that he had picked up a girl back there and had let her fall, and that her head hit against something—he didn’t’ know what it was—and for me to move her and I hollered and told him the girl was dead.

And he told me to pick her up and bring her to the elevator, and I told him I didn’t have nothing to pick her up with, and he told me to go and look by the cotton box there and get a piece of cloth and I got a big wide piece of cloth and come back there to the men’s toilet, where she was, and tied her, and I taken her and brought her up there to a little dressing room, carrying her on my right shoulder, and she got too heavy for me and she [s]lipped off my shoulder and fell on the floor right there at the dressing room and I hollered for Mr. Frank to come there and help me; that she was too heavy for me, and Mr. Frank come down there and told me to “pick her up, dam fool,” and he run down there to me and he was excited, and he picked her up by the feet. Her feet and head were sticking out of the cloth, and by him being so nervous he let her feet fall, and then we brought her onto the elevator, Mr. Frank carrying her by the feet and me by the shoulder, and we brought her to the elevator, and then Mr. Frank says, “Wait, let me get the key,” and he went into the office and come back and unlocked the elevator door and started the elevator down.

Says Frank Stood Guard.

Mr. Frank turned it on himself, and we went on down to the basement and Mr. Frank helped me take it off the elevator and he told me to take it back there to the sawdust pile and I picked it up and put in on my shoulder again, and Mr. Frank he went up the ladder and watched the trapdoor to see if anybody was coming, and I taken her back there and taken the cloth from around her and taken her hat and shoe which I picked up upstairs right where her body was lying and brought them down and untied the cloth and brought them back and throwed them on the trash-pile in front of the furnace and Mr. Frank was standing at the trapdoor at the head of the ladder.

He didn’t tell me where to put the things. I laid her body down with her head toward the elevator, lying on her stomach and the left side of her face was on the ground the right side of her face was up and both arms were laying down with her body by the side of her body. Mr. Frank joined me back on the first floor. I stepped on the elevator and he stepped on the elevator when it got to where he was, and he said, “Gee, that was a tiresome job,” and I told him his job was not as tiresome as mine was, because I had to tote it all the way from where she was lying to the dressing room and in the basement from the elevator to where I left her.

Frank Washed Hands, He Asserts.

Then Mr. Frank hops off the elevator before it gets even with the second floor and he makes a stumble and he hits the floor and catches with both hands and he went around to the sink to wash his hands and I went and cut off the motor and I stood and waited for Mr. Frank to come from around there washing his hands and then we went on into the office and Mr. Frank, he couldn’t hardly keep still. He was all the time moving about from one office to the other. Then he come back into the stenographer’s office and come back and told me, “Here comes Emma Clark and Corinthia Hall,” I understood him to say, and he come back and told me to come here and he opened the wardrobe and told me to get in there, and I was so slow about going he told me to hurry up, damn it, and Mr. Frank, whoever that was come into the office, they didn’t stay so very long till Mr. Frank was gone about seven or eight minutes, and I was still in the wardrobe and he never had come to let me out, and Mr. Frank come back and I said: “Goodness alive, you kept me in there a mighty long time,” and he said: “Yes, I see I did; you are sweating.” And then me and Mr. Frank sat down in a chair. Mr. Frank then took out a cigarette and he give me the box and asked me did I want to smoke, and I told him, “Yes, sir,” and I taken the box and taken out a cigarette and he handed me a box of matches and I handed him the matches back, and I handed him the cigarette box and he told me that was all right I could keep that, and that I told him he had some money in it and he told me that was all right I could keep that. Mr. Frank then asked me to write a few lines on that paper, a white scratchpad he had there and he told me what to put on there and I asked him what he was going to do with it and he told me to just go ahead and write, and then after I got through writing Mr. Frank looked at it and said it was all right, and Mr. Frank looked up at the top of the house and said, “Why should I hang? I have wealthy people in Brooklyn,” and I asked him what about me and he told me that was all right about me, for me to keep my mouth shut and he would make everything all right.

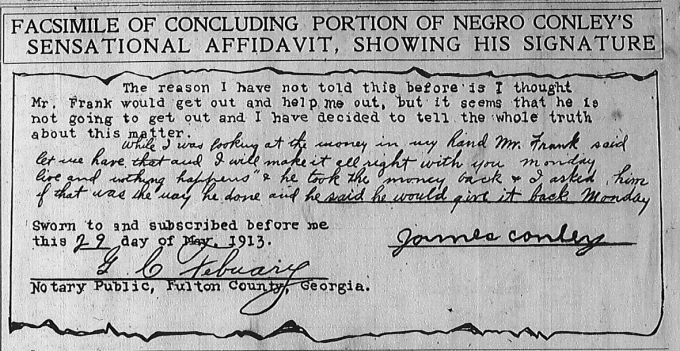

And then I asked him where was the money he said he was going to give me, and Mr. Frank said, “Here is $200,” and he handed me a big roll of greenback money and I didn’t count it. I stood there a little while looking at it in my hand and I told Mr. Frank not to take out another dollar for that watch man I owed, and he said he wouldn’t—and the rest is just like I told it before. The reason I have not told this before is I thought Mr. Frank would get out and help me out, but it seems that he is not going to get out, and I have decided to tell the whole truth about the matter.

While I was looking at the money in my hand, Mr. Frank said: “Let me have that and I will make it all right with you Monday if I live and nothing happens.” And he took the money back, and I asked him if that was the way he done, and he said he would give it back Monday.

JAMES CONLEY.

Sworn to and subscribed before me the 29th day of May, 1913.

G. C. FEBUARY,

Notary Public, Fulton County, Ga.

If the latest confession of James Conley is true, then Leo M. Frank killed Mary Phagan, and the killing was apparently accidental.

Conley swears Frank told him he had picked up a girl and let her fall, and that her head hit something. When the body of Mary Phagan was found there were deep wounds and abrasions on the skull. Conley does not say specifically whether it was all an accident. Conley says when he reached the girl she was dead.

In his confession Conley admits he himself tied a cloth about the dead girl’s head, so he could carry her to the basement at Frank’s direction. The police theory has been that the murderer of Mary Phagan accidentally knocked her against a piece of machinery, then became frightened and finished the job by strangling her with a rope. Conley makes no mention of a rope. From his story, therefore, it would appear that the deep furrows in the dead girl’s flesh giving credence to the theory of strangulation were produced by the cloth which the negro himself tied about the girl’s body. Conley insists the girl was dead when he first saw her.

Turning the Suspicion.

Frank superintended the carrying of the girl’s body to the cellar, Conley swore, displaying great nervousness. Then, when the body had been deposited on a trash pile, Frank took the negro back upstairs and laid plans for throwing suspicion on the negro.

At Frank’s direction, Conley says, he wrote the notes presumed to have been found with the body of Mary Phagan. Frank took the notes, gave the negro a cigarette, remarked, “Why should I hang?” and told him he (Frank) would see that everything would come out all right for him (Conley.)

Frank then gave the negro a roll of bills, which he said was $200. In a few minutes he took them back, promising to make it all right the following Monday morning.

Whether the killing was premeditated murder, or murder after Frank had unintentionally injured Mary Phagan, or accident pure and simple, remains to be determined.

“Betrayed Himself.”

If Conley’s confession is true, Leo M. Frank killed Mary Phagan by accident, and in nervous, half-crazed efforts to dispose of the body laid himself liable to the very charge of murder he sought to avoid.

He knew he was alone in the factory with the girl, that sensational reports would follow discovery of the body and feared his story of an accidental killing would be discounted. Therefore, he bribed the negro to help him dispose of the body—fearful lest the groundless charge of murder be made against him.

Frank told Conley—so the negro says—that he picked the girl up and let her fall, her head hitting something hard. The girl was dead, Conley says, when he first saw her, and in an effort to facilitate removal of the body he, Conley, tied a stout cloth around the head. It was this cloth, tightly drawn over the dead girl’s features, which gave rise to the theory of strangulation.

Examination disclosed a fractured skull, caused by contact with a heavy substance. This wound undoubtedly followed the dropping of the girl’s body against “something hard.”

Frank’s statements to Conley while the girl’s lifeless body was not yet cold throw no light on the dramatic scene ending in Mary Phagan’s death. Whether they were on intimate terms and he was fondling her, or whether they were struggling when he “picked her up,” is still a mystery—a mystery made all the more deeper by the absence of any details pertaining thereto in the negro’s narrative.

* * *

Atlanta Georgian, May 29th 1913, “Negro Conley’s Affidavit Lays Bare Slaying,” Leo Frank case newspaper article series (Original PDF)