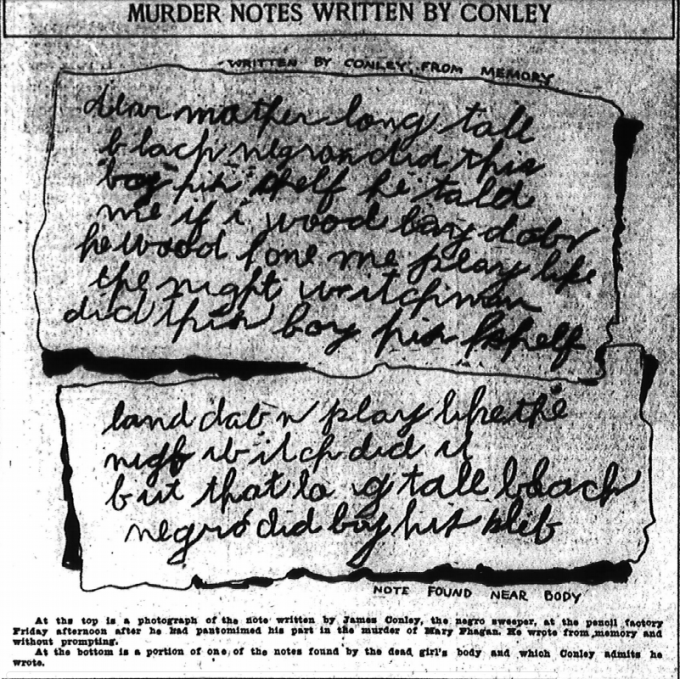

At the top is a photograph of the note written by James Conley, the negro sweeper, at the factory Friday afternoon after he had pantomimed his part in the murder of Mary Phagan. He wrote from memory and without prompting. At the bottom is a portion of one of the notes found by the dead girl’s body and which Conley admits he wrote.

Another in our series of new transcriptions of contemporary articles on the Leo Frank case.

Atlanta Journal

Sunday, June 1st, 1913

The Weak Points in the Negro’s Story Are Shown in One Analysis and the Points That Would Seem to Add to Its Reasonableness Are Weighed in the Other.

Below are given analyses of the negro, James Conley’s latest statement or confession from two viewpoints. In one analysis the negro’s statement is weighed with the idea that Conley has not told the whole truth, that he is endeavoring to hide his own responsibility in an accusation of Mr. Frank, who is innocent of the crime, is the victim of a chain of circumstances which link his name with suspicion. In the other analysis Conley’s confession is discussed from the standpoint of the man who regards it as being truthful and its points are argued from that partisan angle. The Journal presents these discussions without any wish to influence any reader to either view but simply for whatever news value they may have in throwing light on the case.

Conley’s Story Is Unreasonable from This Viewpoint

Those who have all along argued that Superintendent Leo M. Frank could not have had any hand in the murder of Mary Phagan, the pencil factory girl, whose body was found in the factory basement on Sunday morning, April 27, are, since the confessions of James Conley, the negro sweeper, more than ever convinced that Frank is innocent.

They now hold to the theory that the negro not only took the girl’s body to the factory basement and wrote the notes found beside it, as he says in his confession, but that he, and he alone, committed the murder.

Calling attention to the fact that Frank is an educated, gentle and refined man, and one whose past record and reputation are such as to win the respect and loyalty of his friends and acquaintances, all of whom still believe in him, despite certain unfortunate circumstances which militate against him, they make the flat assertion that Frank, being the man he is, could not have committed the brutal crime charged to him by the grand jury.

After asserting this proposition, those who believe in Frank’s innocence and the negro’s guilt undertake to analyze the evidence adduced at the coroner’s inquest and the negro Conley’s affidavit of confession. In doing this they seek to substantiate the statement made by Frank at the inquest and to point out the improbabilities and weakness of the negro’s story.

Frank’s Clear Statement.

Emphasis is laid upon the remarkably clear and unwavering detailed statement of Frank at the inquest, when for three hours he was put through a rapid fire cross-examination by the coroner, who was prompted by the solicitor general. Without hesitation, and without once entangling himself, it is claimed, Frank answered every question concerning even the most minute incidents in which he figured on Saturday, April 26, the day of the murder.

And it is pointed out that the other witnesses corroborated every material statement he made.

Taking up the negro’s affidavit of confession, those who hold to the theory that he committed the murder reason as follows:

Conley’s statement that on Friday afternoon Frank told him to meet him Saturday morning about 10 o’clock at the corner of Forsyth and Nelson streets, as he wanted him to do some work, is not to be believed, because if Frank had wanted the negro for any purpose he would have told him to report at the factory.

That it is impossible to assume that Frank premeditated the murder, because he is not that kind of a man, and even if he was, he had no way of knowing that the little Phagan girl would show up at the factory Saturday.

That had he known the girl would come, and had he planned to murder her and employ the negro’s services in hiding the body, he would not have had Conley meet him at a prominent street corner, a half block from the general offices of the pencil factory.

In Hiding All Morning.

That as a matter of fact Conley never met Frank on the streets at all, but was in hiding practically all the morning in a pile of boxes beside the stairway, where he could see everything that occurred in the front part of the factory on the lower floor without being seen himself.

Conley admits he was drinking that Saturday morning and admits he was in hiding in the boxes, but says he did not come to the factory until between 10:30 and 11 o’clock, following Frank from Nelson and Forsyth streets at his (Frank’s) suggestion.

Frank did not leave the factory to go to Nelson street until about 10 o’clock. Miss Mattie Smith, an employe who came for her money Saturday morning at 9 o’clock, says she saw a negro sitting on the box at the front of the factory. She says it was either Conley or Gordon Bailey, another one of the negroes employed at the factory. She did not notice which.

Bailey’s movements have been accounted for, and he was not at the factory that Saturday morning. When Conley saw Miss Smith enter through the closed front doors he followed her in and secreted himself in the pile of boxes. He knew some of the employes would be coming for their money and he might have intended to rob some of them. He was looking for an opportunity.

Left Factory at 9:30.

Miss Smith, according to her own statement and those of several persons who were at the factory, declare she arrived about 9 a.m., and she left about 9:20, and that N. V. Darley, the manager, walked down the steps to the front door with her.

In his confession Conley says he saw Miss Smith and Darley come down and to the detectives he described the kind of dress the young woman wore. This was at 9:20 before Frank ever went over to Nelson street.

About fifteen or twenty minutes after Miss Smith’s departure Superintendent Line, of Montague Bros., and Wade Campbell, an inspector at the pencil factory, left the pencil factory. Conley says he saw them, yet this happened before Frank went to Nelson street.

A few minutes before 10 Frank, accompanied by Darley, left the factory, walked to the corner of Forsyth and Hunter streets, where they drank a soda water and separated, Frank going to Nelson street and Darley to the Montgomery moving picture theater on Peachtree street.

Frank says he arrived at Montag Bros. on Nelson street a few minutes after 10 o’clock, and his statement is corroborated by a half dozen or more persons there. Darley says he walked to the moving picture theater, going by way of Hunter to Broad, Broad to Viaduct place, along Viaduct place to Whitehall, and thence to the theater on Peachtree. He says he arrived there three or four minutes before the theater opened and that it was scheduled to open at 10 o’clock.

Conley declares he saw Darley leave and that he went away by himself. The latter states that he never returned to the factory after he went out with Frank.

Some time between 10:30 and 11 o’clock E. F. Holloway, the factory timekeeper, talked in the entrance of the factory with a peg leg negro driver for Pittsburg Plate Glass company who had brought a load of boxes. Conley says he saw the two men talking. This was while Frank was on Nelson street.

Conley tells of other persons who came in and went out again after thne [sic] hour whnen [sic] Frank returned to the factory which was a few minutes after 11 o’clock, he having hurried back because of a telephone call from Miss Hall, the stenographer, who was helping him that morning.

The negro says he did not see Mary Phagan enter the factory at 12:10 o’clock, that he had drunk a half pint of whiskey and several beers and dozed some while hidden behind the boxes. However, he recalls having seen L. A. Quinn come in, and according to the testimony at the inquest Quinn arrived at the factory about 12:15 or 12:20, within five or ten minutes after the girl.

What Mr. Frank Said.

Quinn left about 12:25. In Frank’s statement at the inquest, he said he left the factory to go to lunch about 1 o’clock; that just before leaving he walked upstairs to the fourth floor where Harry White and Arthur Denham, two machinists, were working and where Mrs. White was talking with her husband. He said he announced to them that he was going out and would lock the front doors, and that if any of them cared to get out before he returned from lunch they had better go then. Mrs. White left and Frank followed her out, locking the doors. White and Denham continued at work on the fourth floor.

Frank testified that after leaving the factory he caught a Washington street car; that he arrived at his home, 68 East Georgia avenue, about 1:20 and found his wife and Mrs. Selig his mother-in-law, dressed and ready to go to the grand opera matinee, which opened promptly at 2 o’clock; that he told them good-bye, ate lunch with Emile Selig, his father-in-law, and lay down for a few minutes; that he left home about 2 o’clock to go back to the factory; that he walked to Glenn street where he boarded a Washington street car; that on the way he met his aunt and his cousin from Athens; that after getting on the car he saw J. C. Loeb and chatted with him until the car reached the corner of Hunter and Washington streets, where it was halted by the Memorial day parade; that he left the car there and walked west on Hunter to Whitehall, stopping at the corner of Hunter and Whitehall a moment to view the parade, then proceeding north along Whitehall; that in front of M. Rich & Bros.’ store he met Miss Rebecca Carson, a forelady at the factory, to whom he spoke; that he got through the parade at the corner of Whitehall and Alabama and went into Jacobs’ pharmacy, where he purchased some cigars after which he proceeded along Alabama to Forsyth street and down Forsyth to the factory, arriving there about 3 o’clock; that he went into the office on the second floor, removed his hat and coat and walked up the fourth floor to see if White and Denham were still at work; that they were concluding their work and about ten minutes later came by the office where White obtained from him an advance of $2; that White and Denham then left.

What Conley Claims.

As against this detailed statement of Frank’s Conley says that about 1 o’clock Frank came to the top of the stairs on the second floor and whistled twice for him to come up; that when he got up the steps Frank, who appeared to be highly excited, said he had picked up a girl back in the metal room and had let her fall, her head striking against something; that Frank told him to go back there and bring her out; that he went back and found the girl lying on her face dead; that he came back and told Frank she was dead, and Frank told him to go bring her out; that he asked how he was to do it, and Frank told him to go into the cotton room and get a piece of bagging; that, while he was tieing the girl’s body in the bagging, Frank remained at the head of the stairs and watched that he started out with the girl’s body on his shoulder and, after walking for about fifty or seventy-five feet, he dropped it; that he then went back to Frank and told him it was too heavy; that Frank came and took the feet and he the head; that they carried it in this way to the elevator; that Frank went into the office and got the key to the elevator switch-box; that Frank ran the elevator to the basement and helped him get the body off; that Frank directed him to carry it back to the sawdust pile in the rear of the basement; that, while he was obeying, Frank climbed up the ladder, poked his head through the cubby hole on the first floor and kept a watchout; that after he had deposited the body in the sawdust pile he came back and ran the elevator up to the first floor, where Frank got on and rode with him on up to the second floor; that Frank went to the sink to wash his hands while he (the negro) shut off the elevator motor; that they both then went into the inner office; that soon after their arrival some one was heard approaching, and Frank put him in a wardrobe; that Frank went into the outer office to talk with the persons who had come in and was gone about seven minutes before he came back and let him out of the wardrobe; that they then sat down in the office, where Frank got him to write and talked with him for several minutes, telling him that he was a good boy and he would not forget him; that, after obtaining the notes, Frank gave him a roll of money, but took it back a little later, saying he would see him Monday; that Frank offered him a cigarette, and he found $2.50 in the cigarette box, which Frank told him he could have; that a few minutes later Frank led him out and to the stairs, and that he left and went to a nearby beer saloon.

The negro says he noticed the clock when he came back to get the cotton bagging to tie up the girl’s body, and that it was four minutes to 1. He states that he left the factory about 1:30.

Couldn’t Have Happened.

The incidents related by the negro could not have possibly been enacted within thirty minutes and, according to the testimony of witnesses, Frank was at home, eight or ten blocks away, at 1:20.

What is more plausible and more probable is that Conley, from his hiding place, saw Mary Phagan enter the factory, and peering up the steps saw her go from the office back to the metal room in the extreme rear of the building, three or four hundred feet away (it being assumed that she went back to her dressing room for something or to the women’s lavatory. He noticed she carried a silver mesh bag and probably slipped up the stairs and followed her back with the purpose of robbing her. The negro closed the big doors leading to the metal room and accosted the girl, knocking her in the head. He then tore the ruffle from her underskirt and knotted it around her neck and when he went after the bagging to tie around the body he obtained the cord which he also tied around her neck.

Conley evidently hid in the metal room until Frank went to lunch when he brought out his grewsome burden to the elevator. The front office door is seldom locked so he had no difficulty in obtaining the key to the elevator switch, and having been accustomed to operating the elevator he ran it down to the basement without trouble.

The negro must have dragged the body by the cord from the elevator to the sawdust bin in the rear, for on the day after the crime there was a plain trail indicating that something had been dragged from the elevator to the sawdust bin and when the body was examined Sunday morning by the officers the eyes and mouth were full of dirt, the face was scratched, the dress and one of the stockings was torn and there was an abrasion on the left leg which appeared to have been scrapped against something.

Wrote the Notes.

After leaving the body the negro ran the elevator back to the second floor and went into the opened outer office where he wrote the notes and where there is always lying around the kind of pencil pads upon which the notes were written. He then took the notes, climbed down the ladder into the basement and laid them beside the body, after which he pulled the staple on the rear door and made his escape. The front doors were locked while Frank was at lunch and this was the only way he could get out. Evidence at the inquest showed that the staple had been drawn from the rear door.

It is hard to believe that Frank if guilty would have shared his secret with anyone, much less a negro, and even had he done so he would have most likely made more explanations than are given by the negro.

With the negro in possession of his secret Frank would without doubt have let him retain the roll of bills and almost anything else he wanted. That portion of the negro’s story about Frank slipping him $2.50 in a cigarette box seems too silly to believe. Had he been guilty and desired to give the negro something he would have done so openly.

Little if any credence can be attached to the negro’s declaration that Frank kept murmuring “why should I hang, when I have got rich kinfolks,” and the same is true of the negro’s allegation that Frank explained the dictation of the notes by saying he was going to send them to his mother.

The negro had written the notes and he knew they were designed to fix the crime on some other negro. He couldn’t, as he says, have believed they were wanted merely as a sample of his handwriting. If Frank were guilty and had taken the negro in his confidence, as the latter claims, it goes without saying that Frank would have made some effort to see him and get him out of the way after suspicion began to point at him (Frank).

Things to Be Explained.

Then, too, the negro must explain why it was that on the Monday following the crime he remarked to Herbert Schiff, the assistant superintendent, that he would give a million dollars if he was a white man so that he wouldn’t be bothered. He must also explain why he was washing his shirt on the day that he was arrested. The statement that he had only one shirt and wanted to be presentable at the inquest to which he had been summoned, will not suffice.

The above represents the theory of those who believe that the negro has not told the whole truth, but is trying to save himself by putting the crime on Frank.

Conley’s Story Stands Test in This Analysis

There are several strong points in the detailed confession of the negro sweeper, James Conley, in the opinion of those who accept the negro’s last affidavit.

All students of the mystery are disposed to admit that Mary Phagan met her death on the second floor of the pencil factory. Whether Conley killed her or whether Frank killed her, the negro would hardly imagine and fit together such details as he has fitted together and enacted, describing vividly the scenes on the second floor. Then, too, there was the tell-tale evidence of blood on the floor there and hair on a mashines [sic] sharp point. Whoever killed Mary Phagan killed her on the second floor of the pencil factory, it seems probable.

If the negro killed her, why should he have cared to move the body?

Would it not have cast a suspicion at once upon others in the factory, if the body had been left where negroes ordinarily would not be bold? Would it have incriminated the negro workers, if found there, as it did once when it was found in the basement?

Some one other than the negro might have been interested in getting the body, damning accusation of a crime done on the second floor, away from that floor.

Illogical would have been any initiative on his part to remove the body. Would it have been reasonable still to suppose that the negro, of his own accord, would have faced the momentary risk of exposure entailed by carrying the body out from concealment at the rear, to the front, where anyone might come in or go out and seem, and so to the basement either by stairs and ladder or by elevator—all to accomplish the directly opposite of what the negro’s logical desire would have been?

If the negro had killed the girl in the cellar, for example, would it not have been natural on his part to want to lay her body at some such place, say, at the door of the factory office?

But wouldn’t he have left the body wherever it lay, and fled?

Yes he moved it. And he returned to work Monday morning.

Realism of Statement.

The strength of the negro’s statements is in their realism. Their weakness consists in the fact that they have emerged from a mesh of lies. The negro lied flatly at first. Why? Self-preservation. He knew nothing of law, and instinct to save his own neck made him swear that he knew absolutely nothing about the murder—that, and perhaps, also, the hope of reward for silence. Had his ignorance been less, he might have made a clean statement early in the investigation. But he lied. Afterward he told a partial truth. The detectives knew at once that there was more than he had told, and they urged him to reveal the rest. He revealed more, acknowledge that he had lied. They knew he still was lying, and they dug for more. Then they opened up the vein of information that they sought.

The minute the negro admitted he knew anything at all about the crime he was in for the whole story. It seems reasonable that his mentality is too low for him to create the fiction of a yarn which would fool the detectives—who have every phase of the case in mind or at ready command. Could any person—even one of the detectives—fabricate a story that would fit in with all the known circumstances of this or any other real case?

There remain crudities in the negro’s story. It is improbable, seemingly, that Frank should exclaim, “Why should I hang!” to the negro. Yet he may have said that in effect, without melodrama. It is improbable that Frank premeditated the crime, if he did commit it, and summoned the negro to the factory in advance. Yet that might be merely a tissue of the original falsehood which the negro has been trying to harmonize with his present story. Perhaps the negro went to the factory for some natural purpose that took him to the basement, and found the dark corner behind the elevator a good place to rest and snooze when he came out. It is improbable that Frank deliberately called the negro in to help dispose of the body. But could it have been possible that he was looking around to see if the coast was clear before he started with the body, when his eyes met those of the astonished negro beside the elevator, and he realized that an accessory had been forced upon him? Then there is the possibility that his lack of strength to lift the body made help necessary. He is a slight man; the negro is stout.

Accounting for Mistakes.

Perhaps there are mistakes in the sequence of the negro’s story. Yet that might be natural. It is a most difficult task to remember what you have done in exact sequence. Try it. What did you do day before yesterday? What did you do yesterday—act by act, minute by minute?

Exact sequence might be immaterial. The thing is, if a lie is being told out of the whole cloth, even a plausible semblance of sequel is impossible. That is one absolute test that a lie cannot stand. A man may say he rode to town at noon on a trolley car. He heard the noon whistles blow, he swears. Yet it may be proved on the contrary that all cars were stopped for two hours, from 11 to 1 o’clock, on that very day. That is an illustration.

On the face of things it can be argued, then, that the negro is lying, now with regard to the larger facts. His tale is constructed too admirably, it is woven too subtly with corroborated fact, it can claimed to be the product of his imagination—or that of any very intelligent person, either.

There is the wardrobe, for instance. Would anyone have imagined such a superfluous incident as that, swearing he hid in the wardrobe in the office when somebody called Frank?

There is another point, the crocus sack that was used to wrap the girl’s body in. It is entirely superfluous. No blood-stained crocus sack was found on the trash pile where Conley says he threw it, in the basement; yet the girl’s hat and one shoe and her ribbon were found there. The mention of crocus sack injected something entirely new into the known case. Conley does not even suggest an explanation of why no one noticed it. It was there on the trash pile, that’s all he knows. Nor does he explain the girl’s parasol being found at the bottom of the elevator shaft. The last time he saw it, it was on the floor near where he picked up her body. In short, there are things which Conley does not attempt to explain. He does not presume to illuminate every point. If he did, would his story be so credible?

The negro told a story in detail and swore to it. Several hours later he repeated that story—and acted it—at the factory; and his repetition corresponded with the original.

The negro Jim Conley may be capable of a crime like this. But it is unreasonable to condemn him therefore. It would be equally unreasonable to accuse anybody of any crime of which he is capable. That is not the standard by which Jim Conley must be judged.

It is right here that the great difficult comes in about believing Jim Conley’s story. Leo M. Frank’s most intimate friends believe him incapable of any crime, much less of such an atrocious deed as the murder of Mary Phagan. If the negro sweeper’s accusation is to be accepted, it follows that Frank is possessed of what science knows as a dual personality. The personality that his friends know would never have harmed the little girl. The personality that the negro Conley paints is something fearful.

The ascribe the crime to Frank implies necessarily, too, that he planned his own escape from it, deliberately, astutely, cunningly. Yet if he committed the crime, the rest would have been nothing but logical. Why not clear his own skirts by directing suspicion elsewhere? Why not employ notes, get some one else to write them, shift the whole matter by a well though and artfully devised program with all details foreseen, all except that every negro employed around the factory would stand pat and none of them would run?

There is wealth of realism in the negro Conley’s statement, his “confession,” or explanation, or whatever one has a mind to call it.

He added something entirely new to the case when he said he found the body away around at the back near the women’s lavatory. No one had suspected that it lay there at any time. There had been nothing at all even to suggest that.

Several Things Explained.

There is his story about the body getting heavy and slipping from his shoulder and falling heavily to the floor just as he reached the dressing room. That explains what has been regarded as blood, found on the floor there. It explains the bruises on Mary Phagan’s dead face, caused by the face hitting on the floor after she was dead. There is the vivid detail about the elevator bar being up, so that he and Frank didn’t have to stoop when they put her body on the elevator floor; about Frank standing astride the body’s limbs when he ran the elevator down, its feet being close to the corner where the rope runs; about Frank climbing the ladder and standing at the top of it with his head through the trap door on guard while the negro took the body back through the gloom.

Incidentally, the negro has not stated that he put the notes beside the body. If they were found there, his story implies that they must have been put there by somebody other than himself.

If the negro were lying now, why wouldn’t he tell the story differently?

There is the further realism, when he quotes Frank, at the top of the ladder: “Gee, that was a tiresome job!” and says: “And I told him his job was not as tiresome as mine was, because I had to tote it all the way from where she was lying.”

It is gratuitous, too, unless fact is involved, to recite that Frank jumped aboard the elevator before it reached the street floor level and fell against the negro, throwing his arms around the negro. It would seem to be gratuitous, again, unless it is the truth that is being told, when the negro says that Frank was so anxious to get off at the office floor that he jumped out of the elevator before it go to that level, and tripped and fell on his hands and knees.

Statement Reasonable.

Read Conley’s statement on the main facts, and you find him just as reasonable, it can be claimed. For instance, he recites that just after he had finished writing the notes at Frank’s dictation, in the office after Frank had washed his hands, “I asked him why he wanted to put that about the night watchman in the note, and he said, “That’s all right. I’ll fix that.” Then, swears the negro, Frank put both notes on his desk and put the inkstand upon them.

“And I handed him the cigarette box and he told me that was all right, I could keep that; and I told him he had some money in it and he told me that was all right, I could keep that.”

Did imagination furnish that detail in the negro’s story? Or this?

“He said, ‘Here is $200,’ and he handed me a big roll of greenback money, and I didn’t count it. I sat there a little while looking at it in my hand, and I told Mr. Frank not to take out another dollar for that watch man I owed.”

He referred evidently to weekly payments on the installment purchase of a watch. The lease of a watch betrayed later the negro’s lie that he could not write, and opened the way for the whole confession.

And if the negro were lying, would he supply the very superfluous garnishment of the incident he recites about Mr. Frank having passed close to him in the factory the next Monday morning and having whispered as he went by, “Be a good boy, now.”

The above is an analysis of the negro’s statement from the standpoint of those who regard it as reasonable and truthful and is given simply as representative of that viewpoint.

* * *

Atlanta Journal, June 1st, 1913, “Conley’s Statement Analyzed From Two Different Angles,” Leo Frank case newspaper article series (Original PDF)