Another in our series of new transcriptions of contemporary articles on the Leo Frank case.

Another in our series of new transcriptions of contemporary articles on the Leo Frank case.

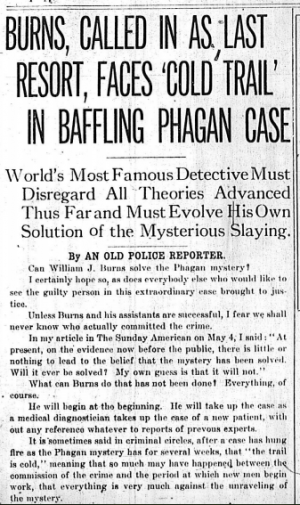

Atlanta Georgian

Sunday, May 18th, 1913

World’s Most Famous Detective Must Disregard All Theories Advanced Thus Far and Must Evolve His Own Solution of the Mysterious Slaying.

By AN OLD POLICE REPORTER.

Can William J. Burns solve the Phagan mystery?

I certainly hope so, as does everybody else who would like to see the guilty person in this extraordinary case brought to justice.

Unless Burns and his assistants are successful, I fear we shall never know who actually committed the crime.

In my article in The Sunday American on May 4, I said: “At present, on the evidence now before the public, there is little or nothing to lead to the belief that the mystery has been solved. Will it ever be solved? My own guess is that it will not.”

What can Burns do that has not been done? Everything, of course.

He will begin at the beginning. He will take up the case as a medical diagnostician takes up the case of a new patient, with out any reference whatever to reports of previous experts.

It is sometimes said in criminal circles, after a case has hung fire as the Phagan mystery has for several weeks, that “the trail is cold,” meaning that so much may have happened between the commission of the crime and the period at which new men begin work, that everything is very much against the unraveling of the mystery.

This is not necessarily true, however. A cold trail is sometimes the best of all.

Mediocre detectives, like mediocre medical men, often get very fixed ideas and refuse to see new angles, new loopholes, new clews, or to examine new theories.

Very good medical men have pronounced patients incurable, or suffering from this, that, or the other disease, when a real expert brought into the case has gone at the matter from a radically different point of view, told them the true source of trouble, and remedied the evil.

WILL DISREGARD OTHER THEORIES.

If Burns does take up the Phagan case, he will not consider any of the testimony or evidence collected so far until he has first studied out the location of the crime, and from the moment the body was found, he will follow every clew, old or new, on his own line of investigation, without any reference to what may have been developed by the city detectives or at the Coroner’s inquest.

After he has built up his own Frankenstein, he will take the reports of the various detectives, compare them with his own, and from these two reports he may be able to construct an entirely new and different case.

It does not follow that because nothing very positive has yet been discovered the mystery may not be solved; or, if it is not solved within the next few weeks, that it will not be solved within a year, or two years to come.

Burns is a relentless man. He knows no fear. No pull or power can influence him. He never forgives nor forgets. He never lets up. His horizon is broad; His imagination is strong; it is possible that some slight clew, overlooked by our city detectives, may start him on a line of investigation that will solve the mystery. I hope so—yet I am doubtful.

I have talked with Thomas B. Felder, the Atlanta attorney, about the Phagan case and Burns’ proposed connection with it.

Felder has been employed to help bring the murderer of Mary Phagan to justice. He is one of the most intelligent lawyers in Georgia, level-headed, cool, incisive and acutely inquiring.

He has no large fee at stake, but he evidently is profoundly interested in the problem submitted to him.

Felder takes great pride in achievement. He delights to do things, to “put over” unusual and extraordinarily difficult undertakings.

FELDER STAKES REPUTATION.

I think he feels that he must not fall in locating the slayer of Mary Phagan. I believe he has staked a large measure of his professional reputation for astuteness and effectiveness against the seeming improbability of the Phagan case being cleared up.

Burns’ name was brought into this case at Felder’s suggestion.

To my mind, that proves two things. First, that Felder feels he must win at any cost; second, that he feels the chances are against him.

It is in just such emergencies, however, that both Felder and Burns work at their best. The commonplace interests neither; the bizarre, the grotesque, the elusive and the mysterious challenge both to their most intelligent effort.

Felder believes in Burns. He knows Burns’ history, from start to its present status. He recites case after case—scores of them—in which Burns has triumphed over the apparently impossible.

Like that master detective of fiction, Sherlock Holmes, a case either interests Burns immediately or not at all. He either brushes it aside or he grasps it vigorously.

Unlike Holmes, however, Burns never injects morphia hypodermically into his circulation, nor does he play dreamy and severely classical music on a violin now and then.

I understand he is rather fond of playing the pianola, and that he will pause occasionally to hear a phonograph grind out one of George M. Cohan’s rattlety-bang pieces, particularly if it is something or other about the “grand old rag,” star-spangled and glee-o-rious.

Such simple diversions as listening to a phonograph or a pianola, moreover, are to my mind more convincing of mental alertness than hypodermics of morphia.

For the purpose of a fictitious detective creation, habitual injections of morphia are more picturesque by way of accounting for subsequent extraordinary mental agility, perhaps, than pianola recitals; but in this everyday world pianola recitals undoubtedly have brought about many more results that are substantial and practically logical in the detection of crime.

All of which may be more or less a seeming digression from the point primarily in mind—and yet it is well enough to remember that Burns is a human being, an actual person, famous in fact and not in fiction, and that Sherlock Holmes merely is a highly interesting creature of the wonderful brain of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, novelist and short story writer.

In digging into Burns’ remarkable history as an unraveler of criminal mysteries, Felder found one case in New Jersey almost exactly paralleling the case of Mary Phagan in Atlanta.

There a 16-year-old girl was found at the head of a “blind alley” in Jersey City, her throat cut from ear to ear, and her body rudely concealed. Local detectives worked on the case for months; suspects were rounded up, and it was shown that thus and so “might have” committed the crime. But nothing came of these investigations and suspicions.

After a time, public interest in the case began to lull, and when it had all but died out Burns was called in.

The case interested him. He undertook its solution, in his own way and after his own fashion.

In an astonishingly short period of time Burns had fixed the crime upon a degenerate youth in Jersey City, therefore utterly unsuspected by the police.

Burns had seized upon a little bit of a circumstance, entirely overlooked by others who had preceded him, and, finding himself on the right trail, rapidly pursued it to its inevitable end.

There wasn’t much of a fee in it for Burns, but his interest had been whetted by the baffling phases of the case, and when once the Burns interest is whetted it is rapacious.

Again, Felder cites the case of Wilberforce Martin, a rich cotton broker of Memphis, Tenn.

Martin disappeared in London, supposedly with a large amount of money on his person. The flower of Scotland Yard was put on the case, and every effort to locate Martin was exhausted.

Finally, the Scotland Yard detectives, being unable to locate Martin anywhere on the face of the earth, proceeded to locate him somewhere beneath the surface thereof, and they reported that Martin unquestionably had been sandbagged, robbed, and thrown into the Thames, and that his friends, if they desired to recover his body, might do so by dragging the river between such and such points.

Dragging failed to disclose a deceased Martin, however, and so, after a while, Burns was called into the case.

FOUND MARTIN—BUT NOT DEAD.

He went at it in his own way, and pretty soon he said that Martin was not at the bottom of the Thames, never had been there, and, furthermore, never had been sandbagged or robbed.

A few days later Burns turned up Martin, safe and sound, in a little Swiss village, where, for reasons of his own, he had elected to conceal himself for a time.

Naturally Scotland Yard was much chagrined, but there was Martin, alive and kicking, so what could Scotland Yard do but acknowledge its comparative stupidly beside the prowess of Burns.

And that, I think, surely would have delighted Sherlock Holmes, and good Dr. Watson, were there any such persons in reality!

Then, of course, there is the famous and recent case of the Los Angeles dynamiters. That story is so well known, and Burns’ remarkable work in connection with it is so familiar to the public that detail recital of it here would be out of place.

It took him a long time to ferret out the truth of that, but he did it, nevertheless.

That’s Burns, all over—he is untiring and relentless.

It will be seen, therefore, that Mr. Felder’s supreme confidence in Detective Burns is now without reason. Burns is a remarkable man—remarkable for his common sense, his businesslike methods, his attention to the seemingly unimportant and inconsequential, his knowledge of men and their ordinary trend of though, his wide and diversified experience, and his absolutely unalterable determination and persistence.

Maybe Burns can and will solve the Phagan mystery. No person not a party to the crime, or a similar crime or crimes, will fail to hope and pray that he may. Good men and good women stand ready to finance his undertaking to the limit. That much seems assured.

If Burns can not find the slayer of the little girl, who can? I am sure I can not imagine.

CREDIT ALL HIS IF HE WINS.

Burns is not infallible. He has encountered mysteries he could not fathom—mysteries, perhaps, beyond the fathoming of human beings. But he has been most amazingly successful where the crème de la crème of the world’s detective talent has failed.

Unquestionably, he will come into the Phagan case, if he does come, because it appeals to him, because it challenges his genius and his most aggressive ingenuity.

Like an expert surgeon who glories in the successful performance of delicate operations, so Burns glories in solving the most delicate and intricate problems, in unveiling the most obscure mysteries.

The Phagan case will afford Burns a great opportunity further to clinch his right to the title of the world’s greatest detective.

He will fight it out alone and in his own way. He will be accorded the same treatment that other detectives have been accorded in investigating the case.

State, county and city officers will co-operate with him in exactly the same degree, if he wishes, that they co-operated with the other detective talent, local and otherwise, heretofore exploited in the case. That much—no more and no less.

If Burns wins, the credit will be his—if he loses, the loss of prestige and the shame of failure will fall upon Burns’ broad shoulders.

That, however, is the way he likes it to be. He has been placed in that position so many times, and there are so many detectives, real and near, gone to their rewards unwept, unhonored and unsung, and Burns so decidedly and so emphatically still is Burns that—well, it looks as if the right man is to take the job in hand at last.

I sincerely hope so, anyway.

* * *

Atlanta Georgian, May 18th 1913, “Burns, Called In As Last Resort, Faces ‘Cold Trail’ in Baffling Phagan Case,” Leo Frank case newspaper article series (Original PDF)