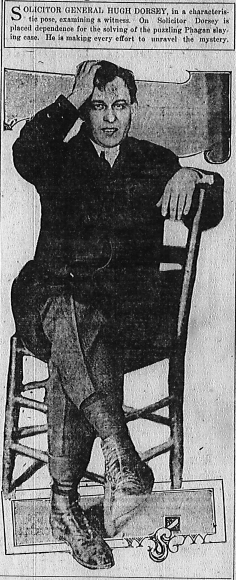

Solicitor General Hugh Dorsey, in a characteristic pose, examining a witness. On Solicitor Dorsey is placed dependence for the solving of the puzzling Phagan slaying case. He is making every effort to unravel the mystery.

Another in our series of new transcriptions of contemporary articles on the Leo Frank case.

NO REAL SOLUTION OF PHAGAN SLAYING MYSTERY

EVIDENCE AGAINST MEN NOW HELD IN BAFFLING CASE WEAK, SAYS OLD POLICE REPORTER

Atlanta Georgian

Sunday, May 11th, 1913

Detectives in Coroner’s Jury Probe Admit They Have Nothing on Which to Convict Anyone in Mysterious Tragedy of Atlanta.

TESTIMONY BROUGHT OUT NO INCRIMINATING POINTS

BY AN OLD POLICE REPORTER.

The most sensational testimony offered at the Coroner’s inquest in the Phagan case was lost sight of entirely by the newspapers.

Juror Langford asked Detective Black, who was on the witness stand: “Have you discovered any positive information as to who committed this murder?”

Detective Black replied, “No, sir, I have not!”

Coroner Donehoo asked Detective Scott of the Pinkerton force on the witness stand:

“Have you any definite information which makes you suspect any party of this crime?”

Detective Scott replied, “I would not commit myself. I am working on a chain of circumstances. Detective Black has been with me all the time on the case and he knows about the circumstances I refer to.”

As you read this over and consider it carefully, you will be impressed by the fact that the two most important detectives engaged for a period of two weeks on the Phagan case testify under oath that they have no positive information as to who committed the crime—in fact really know nothing about it at all.

I am setting down here my own thoughts and ideas, without intending the slightest disrespect to any official, and further, I believe I am at liberty to do so because of Scott’s and Black’s testimony.

MYSTERY STILL WITHOUT SOLUTION.

In The Sunday American of last week I published an article saying that the developments of the preceding week had led nowhere, and that the mystery was then as dark and deep as any mystery that ever puzzled police and detectives.

I can only repeat this statement to-day. I am not in the confidence of any of the detectives, of Solicitor Dorsey, or of Coroner Donehoo, or any of the persons engaged in the attempt to unravel the crime.

I know what the average newspaper readers knows—no more, no less. I walk about the streets a great deal, I ride on the cars and met a great many people who talk about the terrible affair, and I believe I am right in saying that the consensus of opinion now is that the police and detectives are very far indeed from solving the mystery.

In making this statement I do not wish to be understood as casting reflections upon the police or detective force. The men engaged on the case are well-meaning, but of limited experience, and they may have made mistakes.

The infallible detective, like the indispensible man, does not exist.

All detectives are not “man catchers,” and many detectives employ very stupid methods in their work. They can see the obvious things, but they lack imagination. Their minds work like a circular saw, and a knotty problem sometimes stops their minds from working entirely, just as a tangle of knots in a plank being sawed puts the saw out of business.

I pay my respects here to Coroner Donehoo in the way he has handled the case. His examinations of witnesses showed unusual intelligence. His questions were searching and he exhibited a zeal in the public welfare that must not be overlooked. But Coroner Donehoo is not a Sherlock Holmes. He performed his function under the law in a creditable manner. He really wasted hours in asking questions that might have been spared except that there was always a hope that a blind question might catch a witness off-guard and there would be an ensuing revelation.

What did the Coroner’s inquiry develop?

Take first the case of Lee. The testimony against him is that he is the only person KNOWN to have been in the pencil factory, after 6:30 o’clock in the evening until the body was discovered.

Frank testified that he found three “skips” in the clock tape Lee should have punched.

Sergeant R. J. Brown testified that Lee could not have seen the body from the place the night watchman told him he first saw it.

Sergeant L. S. Dobbs testified that Lee, without suggestion from any one, said that the words “night witch” in one of the notes found near the body of the dead girl meant “night watchman.”

F. M. Berry, assistant cashier at the Fourth National Bank, testified that the notes found near the body were in his opinion written by Lee.

Detectives told of finding a shirt with blood stains near the right shoulder in a barrel at the rear of Lee’s house. The indications were that the shirt never had been worn, however.

TESTIMONY FAVORING LEE.

Testimony favoring Lee is that he was not alone in the building until after 6:30 o’clock, and that it can not reasonably be supposed that he would have been able to lure the girl to the factory by any means after this time, or even that the girl would have been alone in that vicinity at that time. There is no evidence to account for her whereabouts between 12:10 and 6:30 o’clock.

Lee’s own testimony was that he did not know the girl and that he never saw her until he came upon the body in the basement of the factory shortly before 3 o’clock Sunday morning.

W. W. Rogers testified that Lee did not appear excited. Other officers who went to the factory Sunday morning corroborated this testimony.

These circumstances conflict with what is known of Lee’s nature. The natural course for Lee, had he been the culprit, it is argued, would have been instant flight.

The framing of the notes to divert suspicion, according to the testimony of persons familiar with the negro nature, was too subtle a plan to suggest itself to Lee’s mind.

What was developed against Frank?

The principal points brought out connecting him with the crime were:

He was the last person known to have seen Mary Phagan. By his own testimony, he saw her at 12:10 Saturday afternoon, April 26, when she appeared at the factory to get her pay. No one was able to swear she was seen after that time.

G. W. Epps, Jr., a boy friend of the Phagan girl, testified that Mary had told him Frank had waited at the door when she left the factory one day and winked at her and tried to flirt. Epps rode to town with her the day she went to the factory to get her money, and was to meet her again at 4 o’clock at Five Points. She did not appear, lending strength to the theory that she never left the factory after once going to get her pay.

FRANK’S CONDUCT WITH GIRLS.

Thomas Blackstock, a former employee, testified that he had seen Frank attempt liberties with girls in the factory.

Nellie Pettis, 9 Oliver Street, testified that Frank had made improper advances to her when she went to get her sister-in-law’s pay at the factory. She said he pulled out a box of money from a drawer and looked at her and then the money and asked: “How about it?”

Mrs. C. D. Donegan, 165 West Fourteenth Street, said she had seen Frank smile and flirt with the girls in his employ.

Nellie Wood, 8 Corput Street, testified that Frank had attempted familiarities with her in his office, and had put his hands on her and had tried to persuade her to remain with him in his office.

Frank testified that he was at the factory Saturday afternoon from 12 to 1 o’clock and from 3 to 6:30 o’clock. Harry Denham, Arthur White and White’s wife were in the factory part of the afternoon, the two men until 3:10. From 3:10 until 3:45 Frank was alone in the factory. Then Newt Lee came and was told by Frank to take the remainder of the afternoon off until 6 o’clock. From about 4 o’clock until 6, Frank again was alone in the factory, so far as the testimony showed.

Lee testified that the crime could not have been committed in the night without his knowledge, as he had gone past the lathe machine on the second floor, where the struggle is believed to have taken place, twice every half hour on his regular rounds.

Lee testified that Frank appeared greatly agitated when he met him at the door of the factory office just before 4 o’clock. He said that Frank seemed nervous and was rubbing his hands in an excited fashion.

J. M. Gantt, a former employee who happened to be in the factory at 6 o’clock, testified that Frank appeared nervous and apprehensive at this time.

UNABLE TO REACH FRANK AT 3.

Call Officer Anderson testified that he tried to telephone Frank at his home after the police had viewed the body at 3 o’clock Sunday morning, but that he could not get him.

W. W. Rogers, former county policeman, who carried the officers in his automobile to the scene of the murder and later to get Frank, testified that Frank, when he saw the officers, began to ask them if “anything had happened at the factory?” and if the night watchman had “found anything” when nothing had been told him at that time as to the tragedy.

Rogers said he saw Frank remove the time slip from the time clock which Lee had punched. Rogers said that there were no “skips” on it, but that it was punched regularly every half hour from 6:30 in the evening until 2:30 the next morning. It was shortly after 2:30 o’clock that Lee told the officers he had found the body. The time slip which later was turned over to Chief Lanford by Frank had three “skips” in it.

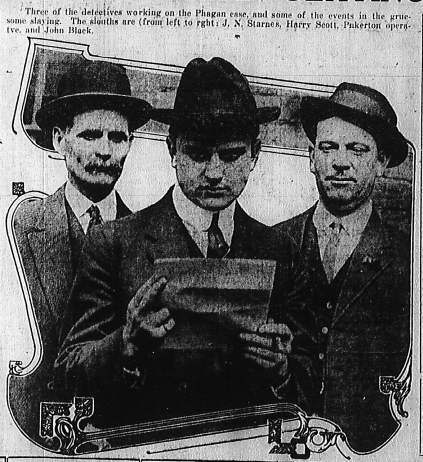

Three of the detectives working on the Phagan case, and some of the events in the gruesome slaying. The sleuths are (from left to right: J. N. Starnes, Harry Scott, Pinkerton operative, and John Black.

Lee testified that Frank had told him the Sunday the body was found that the clock was punched all right and later contradicted himself by saying there were three “skips” in it, and that it “looked queer.”

Lee testified that Frank had told him in a private conference that “they would both go to hell” if Lee maintained his present attitude.

Harry Scott, Pinkeron detective, bore out Lee on this point.

I am inclined to classify this as negative testimony.

Frank is reached and held through a process of elimination.

Testimony pointing toward the innocence of Frank was that of Frank himself.

He said that he had not known Mary Phagan by name before her murder; that he recalled paying her at 12:10 Saturday afternoon, but that she left his office at once and he heard her footsteps dying away as though she had left the building. He said he remained at the factory until 1 o’clock in the afternoon and then went to his home for luncheon, returning about 3 o’clock. He said that he was entirely alone from 4 o’clock until 6, and that he arrived home at 7 in the evening, where he remained. He declared he knew nothing of the tragedy until the following morning. He said that he dreamed during the night that some one was ringing the telephone, but that he did not fully awaken. In this manner he explained his failure to answer the telephone.

Harry Denham, one of the men in the factory Saturday afternoon until 3:10 o’clock, testified that Frank did not appear nervous or agitated when he saw him.

F. M. Berry, assistant cashier of the Fourth National Bank, testified that the notes found by the side of Mary Phagan did not appear to be in the handwriting of Frank.

Lemmie Quinn testified that he was in the office of Frank Saturday afternoon between 12:15 and 12:30, and that he did not see Mary Phagan in the office or anywhere else in the building.

Mr. and Mrs. Emil Selig, Frank’s parents-in-law, corroborated the story of Frank’s movements during the day.

Quinn and other men in the factory testified that they never had seen Frank many any improper advances toward the girls, but that on the contrary he had been most courteous when he had any personal dealings with them, which was not frequently.

Miss Corinthia Hall, one of the employees, said she never had observed Frank attempt any liberties with any of the girls.

Herbert Schiff, chief clerk in the factory, testified that the work which Frank accomplished Saturday afternoon on the financial sheet would have taken any expert five or six hours.

EVIDENCE IS NOT CONVINCING.

I ask would YOU consider this very convincing in the case of either man?

I do not.

But after the Coroner’s inquest the case assumes a new form. The whole matter now rests in the hands of Solicitor Dorsey. I have never met him. All that I heard about him is in his favor. But he has never shown any unusual skill as a detective. He knows criminal law, and he will proceed along the regular lines of bringing the whole matter to the attention of the Grand Jury, and indicting both Frank and Lee. Then will come the trial.

If Detectives Scott and Black are reported accurately in their testimony, as quoted at the beginning of this article, then the prosecution in my opinion has very little upon which to base a successful trial of either of the men now held for the crime. Lee came through the cross-questioning without any discredit at all. The points made against Frank are not of much importance. They may foreshadow something big. They were, of course, sufficient to warrant the Coroner’s Jury in holding him for the Grand Jury.

An indictment by the Grand Jury does not mean that a person is guilty. Far from it.

CRIME SHOULD BE UNRAVELED.

I hope Solicitor Dorsey will be able to unravel the great mystery, and that he will have evidence enough to convince—not only a jury of twelve men, but the entire community as well, of the guilt or innocence of whatever persons, Frank, Lee or others who may yet be caught in the net, of the murder of the innocent little girl.

An indictment by the Grand Jury is a very important legal document. It must be air tight, and held together by such a strong chain of evidence that it can not be broken anywhere. It has to run the whole gauntlet of the law. An imperfect indictment falls of its own weight.

For the battle really begins—not before a Coroner’s Jury, but in the court room, where the law and the facts have precedence over everything else.

When the prosecution in the Phagan case goes into court, it will be faced by one of the best lawyers in the South.

Luther Z. Rosser, big of frame, big of intellect, big in the knowledge of the law and schooled in all the intricacies of its machinery, will be at the opposing counsel’s table, making a battle for his client, turning evidence with his shield from the lance of Mr. Dorsey, sifting every piece of evidence for the jury, challenging every inch of the law to the judge.

And I am told, that he is skillful with the use of the broad sword as he is deft with the rapier.

I am writing thus freely, for the reason that the two detectives, quoted at the beginning of this article, in their testimony gave me the right to discuss the matter in the columns of the newspapers as I am doing.

PRECEDENT HAS NOT YET BEEN VIOLATED.

This is no violation of precedent. It is not for the purpose of establishing the guilt or innocence of any person. It is solely because I am trying to set down what I believe to be the thoughts running through the minds of the average man and woman.

Frank and Lee may be guilty, but it would require a great deal more evidence than has been published in the newspapers to convince me of it.

It may be that Mr. Dorsey has a mass of evidence to present to the jury when it confronts the accused in open court, and overwhelm the defense with sensation after sensation and buttressed fact after buttressed fact.

I do not know whether this is so or not. I give my own opinion for what it is worth. What the detectives and police now have against Frank and Lee at this moment is apparently worthless.

Any day or any hour may bring forth new suspects and the real criminals.

I can not help but sympathize with Frank in being held as he is on the very slight evidence presented against him. At the moment, it would seem as though he were a victim of circumstance and that he would have to take the consequences that follow being the superintendent of the factory and the last person who is said to have seen Mary Phagan alive. And consequences, as George Eliot said, are unpitying.

FRANK’S PAST IN HIS FAVOR.

I said in my article in last Sunday’s American that what is known of Frank’s past is in his favor. I reiterate that. He is a college graduate, a man of culture, has traveled considerably, and stands well among his friends.

Public Opinion that first condemned Lee, then Frank, then both of them, then was ready summarily to dispose of them without waiting for the process of the law, is calmer to-day and anxious for the facts.

I do not mean by this that I believe Public Opinion would acquit Frank without a trial, for the belief prevails that not all of the evidence has been made public. But Public Opinion is willing to “play fair” and hear the facts.

I hope Solicitor Dorsey will continue his investigation while he is weaving his web around Frank and Lee. It may be that they are not guilty. It may be that some other person or persons committed the ghastly deed. It is worth while for our alert prosecutor to watch in all directions for the criminals.

And it may be well for our citizens to keep their minds open and receptive, not acquitting or condemning anybody, no matter of what color, race or creed, until all the facts are known.

We can afford to be patient—even with THE LAW.

The great professor Drummond once asked a little girl to a Glasgow Sunday school for a definition of patience. She replied: “To wait a-wheel, an dinna get weary, to keep yer mouth shut and yer eyes open!”

* * *

Atlanta Georgian, May 11th 1913, “Weak Evidence Against Men in Phagan Slaying,” Leo Frank case newspaper article series (Original PDF)