Another in our series of new transcriptions of contemporary articles on the Leo Frank case.

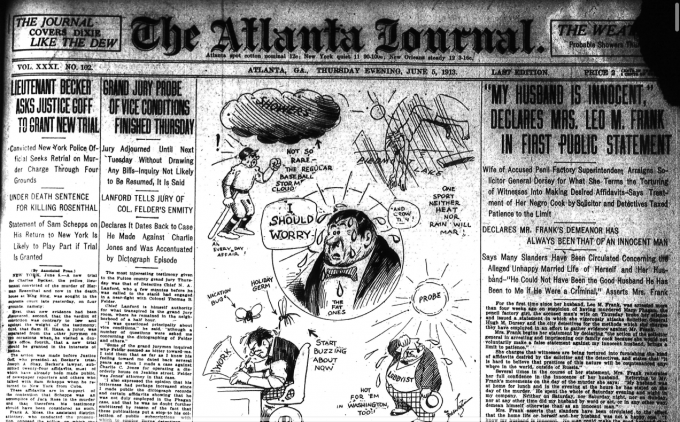

Atlanta Journal

Thursday, June 5th, 1913

Wife of Accused Pen[c]il Factory Superintendent Arraigns Solicitor General Dorsey for What She Terms the Torturing of Witnesses Into Making Desired Affidavits—Says Treatment of Her Negro Cook by Solicitor and Detectives Taxed Patience

DECLARES MR. FRANK’S DEMEANOR HAS ALWAYS BEEN THAT OF AN INNOCENT MAN

Says Many Slanders Have Been Circulated Concerning the Alleged Unhappy Married Life of Herself and Her Husband—“He Could Not Have Been the Good Husband He Has Been to Me if He Were a Criminal,” Asserts Mrs. Frank

For the first time since her husband, Leo M. Frank, was arrested more than four weeks ago on suspicion of having murdered Mary Phagan, the pencil factory girl, the accused man’s wife on Thursday broke her silence and issued a statement in which she vigorously attacks Solicitor General Hugh M. Dorsey and the city detectives for the methods which she charges they have employed in an effort to gather evidence against Mr. Frank.

Mrs. Frank begins her statement by declaring “the action of the solicitor general in arresting and imprisoning our family cook because she would not voluntarily make a false statement against my innocent husband, brings a limit to patience.”

She charges that witnesses are being tortured into furnishing the kind of affidavits desired by the solicitor and the detectives, and states that “it is hard to believe that practices of this nature will be countenanced anywhere in the world, outside of Russia.”

Several times in the course of her statement, Mrs. Frank reiterates her full confidence in the innocence of her husband. Referring to Mr. Frank’s movements on the day of the murder she says: “My husband was at home for lunch and in the evening at the hours he has stated on the day of the murder. He spent the whole of Saturday evening and night in my company. Neither on Saturday, nor Saturday night, nor on Sunday, nor at any other time did my husband by word or act, or in any other way, demean himself otherwise than as an innocent man.”

Mrs. Frank asserts that slanders have been circulated to the effect that the home life or herself and her husband was not a happy one. “I know my husband is innocent. No man could make the good husband that he has been to me and be a criminal,” she declares.

As stated above this is Mrs. Frank’s first public statement since the arrest of her husband, and it will probably be her last. Under the Georgia laws a woman is not permitted to testify for or against her husband. It was for this reason that Mrs. Frank was not summoned as a witness before the coroner’s jury:

STATEMENT IN FULL.

Mrs. Frank’s statement, which comes to The Journal in the nature of a communication, follows in full:

“Atlanta, Ga., June 3, 1913.

“Editor Atlanta Journal, Atlanta, Ga.

“Dear Sir: The action of the solicitor general in arresting and imprisoning our family cook because she would not voluntarily make a false statement against my innocent husband, brings a limit to patience. This wrong is not chargeable to a detective acting under the necessity of shielding his own reputation against attacks in newspapers, but of an intelligent, trained lawyer, whose sworn duty is as much to protect the innocent, as to punish the guilty. My information is that this solicitor has admitted that no crime is charged against this cook and that he had no legal right to have her arrested and imprisoned.

“The following statement from The Atlanta Journal undertakes to give the history of the arrest up to the time the woman was carried to the police station in the patrol wagon, weeping and shouting in a hysterical condition:

“The negress was arrested at the Selig residence shortly after noon Monday upon the order of Solicitor General Hugh M. Dorsey.

“She was carried to the solicitor’s office and that official with Detectives Campbell and Starnes examined her for more than an hour. The woman grew hysterical during the vigorous examination, and finally was led from the solicitor’s office to the police patrol, weeping and shouting: “I am going to hang and don’t know a thing about it.”

“THEY TORTURED HER.”

“They tortured her for four hours with the well-known third degree process, in the manner and with the result stated in the Atlanta Constitution of June 4, as follows:

“’Her husband, who was also carried to the police station at noon, was freed a short while before his wife left the prison. He was present during the third degree of four hours, under which she was placed in the afternoon. He is said to have declared, even in the presence of his wife, that she had told conflicting stories of Frank’s conduct on the tragedy date.

“’After she had been quizzed to a point of exhaustion, Secretary G. C. Febuary, attached to Chief Lanford’s office, was summoned to note her statement in full.

“’It was the longest statement made by the woman since her connection with the mystery. It will be used, probably, in the trial. The negress was calm and composed upon emerging from the examination.’”

“That the solicitor, sworn to maintain the law, should thus falsely arrest one against whom he has no charge and whom he does not even suspect, and torture her contrary to the laws, to force her to give evidence tending to swear away the life of an innocent man, is beyond belief.

INNOCENT SUFFERERS.

“Where will this end? My husband and my family and myself are the innocent sufferers now, but who will be the next to suffer? I suppose the witnesses tortured will be confined to the class who are not able to employ lawyers to relieve them from the torture in time to prevent their being forced to give false affidavits, but the lives sworn away may come from any class.

“It will be noted that the plan is to apply the torture until the desired affidavit is wrung from the sufferer. Then it ends, but not before.

“It is to be hoped that no person can be convicted of murder in any civilized country on evidence wrung from witnesses by torture. Why, then, does the solicitor continue to apply the third degree to produce testimony? How does he hope to get the jury to believe it? He can have only one hope, and that is to keep the jury from knowing the methods to which he has resorted.

“Of course, if he can torture witnesses into giving the kind of evidence he wants against my innocent husband in this case, he can torture them into giving evidence against any other man in the community in either this or any other case. I can see only one hope. And that is, to let the public know exactly what this officer of the law is doing, and trust, as I do trust, to the sense of fairness and justice of the people.

“It is not surprising that my cook should sign an affidavit to relieve herself from torture that had been applied to her for four hours, according to the Atlanta Constitution, “to a point of exhaustion.” It would be surprising if she would not, under such circumstances, give an affidavit.

“This torturing process can be used to produce testimony to be published in the newspapers to prejudice the case of anyone the solicitor sees fit to accuse. It is also valuable to prevent anyone stating facts favorable to the accused, because as soon as the solicitor finds it out, he can arrest the witness and apply the torture. It is hard to believe that practices of this nature will be countenanced anywhere in the world, outside of Russia.

CORROBORATES HUSBAND.

“My husband was at home for lunch and in the evening at the hours he has stated on the day of the murder. He spent the whole of Saturday evening and night in my company. Neither on Saturday, nor Saturday night, nor on Sunday, nor at any other time did my husband by word or act, or in any other way, demean himself otherwise than as an innocent man. He did nothing unusual and nothing to arouse the slightest suspicion. I know him to be innocent. There is no evidence against him, except that which is produced by torture. Of course, evidence of this kind can be produced against any human being in the world.

“I have been compelled to endure without fault, either on the part of my husband or myself, more than it falls to the lot of most women to bear. Slanders have been circulated in the community to the effect that my husband and myself were not happily married, and every conceivable rumor has been put afloat that would do him and me harm, with the public, in spite of the fact that all our friends are aware that these statements are false, and all his friends, and myself, know that my husband is a man actuated by lofty ideals that forbid his committing the crime that the detectives and the solicitor are seeking to fasten upon him.

“I know my husband is innocent. No man could make the good husband to a woman that he has been to me and be a criminal. All his acquaintances know he is innocent. Ask every man that knows him and see if you can find one that will believe he is guilty. If he were guilty, does it not seem reasonable that you could find some one who knows him that will say he believes him guilty?

“Being a woman, I do not understand the tricks and arts of detectives and prosecuting officers, but I do know Leo Frank and his friends know him, and I know and his friends know that he is utterly incapable of com[m]itting the crime that these detectives and this solicitor are seeking to fasten upon him. Respectfully yours,

“MRS. LEO M. FRANK.”

Dorsey Denies Having “Sweated” Negro Cook

Solicitor Dorsey, when acquainted with Mrs. Frank’s statement said:

“The McKnight affidavit was not made in my office and was not made at my direction. Minola McKnight, the negro cook of the Seligs and Franks, was not ‘sweated’ while she was in my office, nor was she ‘sweated’ anywhere else that I know. Merely she was confronted here with her husband.”

* * *

Atlanta Journal, June 5th 1913, “‘My Husband is Innocent,’ Declares Mrs. Leo M. Frank in First Public Statement,” Leo Frank case newspaper article series (Original PDF)