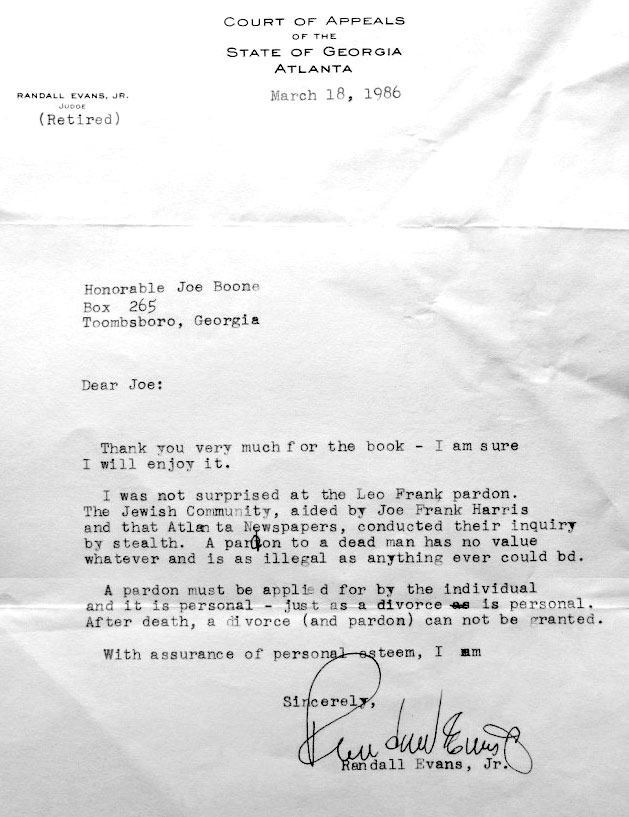

The letter written by retired judge Randall Evans Jr. was listed for sale at Ebay on Jul-29-2015.

The letter written by retired judge Randall Evans Jr. was listed for sale at Ebay on Jul-29-2015.

|

7.25″ by 10.5″ typed letterhead, with ink corrections, March 18, 1986,

one week after the pardon, signed Randall Evans, Judge (retired), Court of Appeals, State of Georgia. Purchased at Ebay on Aug-05-2015 |

By Carolyn Yeager

On May 15, 1983, retired Georgia Appeals Court Judge Randall Evans Jr. published a statement on the Leo Frank case in The Augusta Chronicle-Herald in which he claimed that the proposed posthumous pardon of Frank was “completely ridiculous” because a dead man can’t be pardoned.*

[*the actual article from the Chronicle-Herald cannot now be accessed, but it was commented on and quoted from at the time.]

Evans also said that the evidence of Frank’s guilt “was overwhelming” and described the commutation of Frank’s sentence as “the rape of the judicial process” by Govenor Slaton.

* * *

Seven months earlier in October, 1982, the State Board of Pardons and Paroles had received a formal application for a posthumous pardon for Leo Frank. The application was filed by the Anti-Defamation League, the American Jewish Committee, and the Atlanta Jewish Federation, and directed by a Lawyer’s Committee chaired by Atlanta immigration lawyer Dale M. Schwartz.

“I am not working for Leo Frank or his family,” Dale Schwartz (pictured right) stated publicly. The core of seeking a pardon for Leo Frank, he said, was an attempt to obtain an official repudiation of anti-Semitism and bigotry and to “remove a blot on Georgia history.” As such, the petitioners based their case for pardon not on the legality of the trial and conviction of Leo Frank, but on extra-legal concerns.

“I am not working for Leo Frank or his family,” Dale Schwartz (pictured right) stated publicly. The core of seeking a pardon for Leo Frank, he said, was an attempt to obtain an official repudiation of anti-Semitism and bigotry and to “remove a blot on Georgia history.” As such, the petitioners based their case for pardon not on the legality of the trial and conviction of Leo Frank, but on extra-legal concerns.

Dale Schwartz is the type of Jew who would and did tell the editor of Israel Today in a 1984 interview,

“It was determined that Georgia would perhaps recognize the type of posthumous pardon which did not merely grant ‘forgiveness’ for a crime committed in the past, but rather would ask the defendant to forgive the state for having wrongfully convicted him.”

One of the lawyers working with Schwartz was Charles Wittenstein (pictured right), who was on the staff of the American Jewish Committee, and later the Anti-Defamation League for 20 years (1974-94), in Atlanta.

Said Bill Nigut, the ADL’s southeast regional director:

Said Bill Nigut, the ADL’s southeast regional director:

“There are a number of civil rights issues that he worked on that we point to with a lot of pride and that the entire national organization looks at as being significant achievements. One of them is that Charles was one of the ADL staffers who worked to obtain a posthumous pardon for Leo Frank.”

“The fact that Charles was the key to getting the pardon is something that means a great deal to the Anti-Defamation League.”

The Anti-Defamation League’s National Director from1979 to 1987 Nathan Perlmutter wrote on the subject: “From a broad point of view, the Frank pardon is of no consequence. An innocent Jew was lynched by a mob inflamed by anti-Semitism. It has never happened before or since in the United States.”

They keep pushing the false assumption that Frank was innocent, when all appeals to retry him were found without merit, all the way up to the Georgia, and even U.S., Supreme Courts.

* * *

On March 18, 1986, about a week after the qualified pardon was issued, the following letter was written by former Judge Randall Evans Jr. (pictured left) to Joe Boone of Toomsboro, Georgia (see facsimile above):

Honorable Joe Boone

Toomsboro, GeorgiaI was not surprised at the Leo Frank pardon. The Jewish community, aided by Joe Frank Harris and that [sic] Atlanta newspapers, conducted their inquiry by stealth. A pardon to a dead man has no value whatever and is as illegal as anything ever could bd [sic].

A pardon must be applied for by the individual and it is personal – just as a divorce is personal. After death, a divorce (and pardon) cannot be granted.

Signed Randall Evans Jr.

Can a dead man be pardoned?

It doesn’t seem to be spelled out clearly in the law, However, it appears to be understood in the negative. I found an item on pardons on a webpage about sermons. This sermon-idea included these relevant words:

An item in the May 2, 1985, Kansas City Times reminds us of a story you may be able to use in an evangelistic message. The item had to do with the attempt by some fans of O. Henry, the short-story writer, to get a pardon for their hero, who was convicted in 1898 of embezzling $784.08 from the bank where he was employed. But you cannot give a pardon to a dead man. A pardon can only be given to someone who can accept it.

Back in 1830 George Wilson was convicted of robbing the U.S. Mail and was sentenced to be hanged. President Andrew Jackson issued a pardon for Wilson, but he refused to accept it. The matter went to Chief Justice [John] Marshall, who concluded that Wilson would have to be executed. “A pardon is a slip of paper,” wrote Marshall, “the value of which is determined by the acceptance of the person to be pardoned. If it is refused, it is no pardon. George Wilson must be hanged.”

The clear meaning here from the Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court is that the person to be pardoned must first request a pardon, and then personally accept it. This follows that a pardon cannot be given to a dead man who not only has not personally asked for it, but who cannot accept or decline it.

For we must remember, it is generally assumed that acceptance of a pardon is an implicit acknowledgment of guilt, for one cannot be pardoned unless one has committed an offense. That is the reason a pardon might be rejected.

* * *

In 1943, Georgia decided to do away with the controversy of the Govenor granting pardons, and created a 5-member State Board of Pardons and Paroles by constitutional amendment. The Board is the primary authority in Georgia assigned the power to grant pardons, paroles, and other forms of clemency. Georgia is one of only three states whose governor does not have the authority to grant clemency (as Slaton did for Leo Frank in 1915) although he retains indirect influence by virtue of his power to appoint Board members.