Welcome to the 21st Century, on April 26, 2013, a One Hundred Year Old Murder “Cold Case” Mystery Is About to Be Solved by the Official Legal Record of the Leo Frank Trial Brief of Evidence, 1913

Welcome, Forensic Times Travelers of the Imagination. We are taking you backward down the time web to Atlanta, Georgia, during one of the hottest summers of the early 20th century, the summer of 1913. Three days before Leo Frank is to deliver his unsworn speech to the jury, you check into the Piedmont Hotel with a pocket full of St. Gauden’s $20 Gold Pieces. You will need to call the bellboy and have him order you a tailor to make you a few days of period suits and leisurewear. Do a little research, but $100 tip to the right person should guarantee you a seat at the front journalist table.

The July Term, 1913

Something unusual happened during the month long Leo Frank trial, known as the People of the State of Georgia vs. Leo M. Frank, officiated within the Fulton County Superior Courthouse between July 28 and August 21, 1913. Some might postulate that Mr. Leo Max Frank inadvertently revealed the solution to the Georgian Confederate Memorial Day – Saturday, April 26, 1913 – Little Mary Anne Phagan “Whodunit” murder mystery!

Main Event at the Leo Frank Trial During the Afternoon Session

When Leo Max Frank mounted the witness stand on Monday afternoon, August 18, 1913, at 2:15 p.m., he delivered orally his unsworn, four-hour, pre-written statement to the judge and jury that he had mentally prepared for 3.5 months.

Leo Frank Trial Became the Undisputed Epic Trial of Early 20th Century Southern History

They sat in the grandstand seats of the most spectacular murder trial in the annals of Georgian legal jurisprudence. Dug in and nestled deep within the ass-breaking church pews and various other seating arrangements of the courtroom were nearly 250 jam-packed public spectators, defense and prosecution witnesses, family members, attorneys, journalists, government officials, and staff of various types.

Battle in the Arena

In the center, with their backs to the audience and inside the gladiator arena, were the most important principals seated in ladder-back chairs. They were the State of Georgia’s prosecution team made up of three members, out of which two were gladiators, the Solicitor General Hugh M. Dorsey and Frank Arthur Hooper, vs. eight Leo Frank defense dream team counselors, out of which two were gladiators, good old boy network and seasoned attorneys Luther Zeigler Rosser (who was known as the bludgeon of the wealthy, according to Oney, 2009) and the dapper Reuben Rose Arnold, who together were considered some of the best legal minds in the State of Georgia. They squared off before the thirteen-man tribunal of the presiding judge, the Honorable Leonard Strickland Roan, sitting behind a tall clack rostrum in a high-backed leather chair, separated by the witness stand from the petit jury, who were sworn to decide the life or death fate of Mr. Leo Max Frank.

Stenographers

Crouched and sandwiched between the judge’s bench and witness chair, sitting on the lip of the foot rail attached to the judge’s high-top counter rostrum, was a stenographer squatting low adjacent to the witness and capturing the examinations, in shorthand on legal cap paper, and they were changed regularly in relays.

Encompassing the four major defense and prosecution counselors were an entourage of uniformed police, detectives, and undercover armed security; government staff; and magistrates.

Leo M. Frank Trial for Southerners Was the Most Sensational “Trial of the Century”

The first day of the Leo Frank trial began on Monday morning, July 28, 1913, and led to successive days of tilts, intimations, and scandalous revelations. However, the most interesting day of the trial would occur three weeks deep when Leo Frank sat down in the witness stand on Monday afternoon, August 18, 1913, at 2:15 p.m., to begin a three and a half hour speech to the judge and jury — with one brief intermission halfway through at 4:35 p.m. (before the speech continued onward in time just before the usual adjournment at 6:00 p.m.). No further witnesses were called that day, and the jury could sleep on Leo Frank’s loquacious prepared speech without oath.

The Moment Everyone Was Waiting for in ALL the State of Georgia and South

What Leo Frank had to say to the court became the spine-tingling climax of the most notorious criminal trial in U.S. history, and it was the moment everyone in Georgia, especially Atlanta, had waited for on pins and needles for the first three weeks during the month-long trial.

The presiding judge, Leonard S. Roan, would explain to the jury the unique circumstances and rules concerning the unsworn statement Leo M. Frank would make.

Leo Frank Mounted the Witness Stand

At 2:14 p.m. on August 18, 1913, Leo Frank was called to the witness stand. Leo Frank stood up and stepped forward a few paces, and he then stepped up. When he swiveled around and sat down, the atmosphere in the courtroom changed into a spellbound hush as 250 people closed ranks, leaned forward into peaceful gasping silence. Reuben Rose Arnold had informed Leo Frank if he needed any papers he could come up and retrieve them anytime as needed.

Something Unusual Happened to the Mood

Everyone present was more than just speechless — they were literally breathless — transfixed — sitting on the edges of their seats anticipating every word that came from the mouth of Mr. Leo M. Frank.

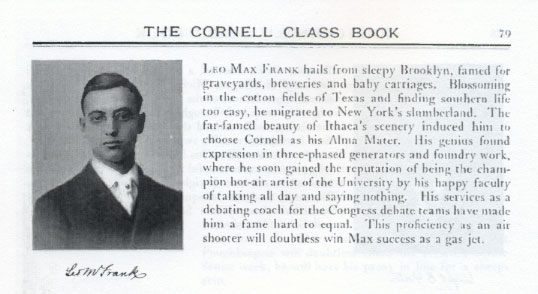

However, listening to Leo Frank, who might have seemed to be manifesting hysteria (Oney, 2003), became challenging at times because he would literally, unbeknownst to the audience, live up to his long-winded and loquacious reputation as Max the successful “gas jet” — it was the reputation Leo Frank had first earned during his four college years at Cornell University, most eloquently captured in his Cornell Senior Year Book roasting (Cornell Senior Year Book, 1906, p. 79).

To say the least, Leo Frank’s infamous courtroom speech to a captivated audience was mind-numbing – that is, three hours and forty-seven minutes long mind-numbing.

To bring his major points home during his almost four-hour speech, Leo Frank had brought out original pages of his accounting books presented them to the jury and discussed them as they were entered into the exhibits section of the official brief of evidence, 1913. Leo Frank went over his quantum mechanical pencil accounting computations he had done on the afternoon of April 26, 1913, for nearly three nauseating hours. Leo Frank’s long rambling rant was meant as a means to show the jury he was far too busy to have murdered Mary Phagan on that fateful Saturday at noon nearly fifteen weeks before.

Follow Along and Get Distracted

One of the disputes at the Leo Frank trial was how long it took Leo Max to do the accounting books. Was it about 1.5 hours as some testified or about 3 hours as other witnesses had testified? Those accounting tabulation sheets utilized by Leo M. Frank are part of the defendant’s exhibits within the appendix of the Trial Brief of Evidence, 1913, and they can be reviewed intermittently while reading Leo’s unabridged trial statement. A 21st century audit of Leo Frank’s trial statement and pencil accounting exhibits reveals that a person with average intelligent and five years of accounting practice could have done everything Leo Frank claimed in about one hour. So what was Leo Frank really doing between noon and 6 p.m. on Saturday, April 26, 1913?

Time and Space Were Bridged as One Universal Presence

If ever a jury of above average men and some of the best legal minds in all of Georgia became one universal focused eye of infinite consciousness, it was in the courtroom at the Leo Frank trial, which would open a seventy-three-year chapter in United States Legal History (1913 to 1986), and the defining date was Monday, August 18, 1913, during the afternoon session, hearing the delivery of an oration by Leo Frank. And even though unsworn, it was still stenographed and entered into the official record.

Before the Apogee

The Atlanta Constitution, Journal, and Georgian newspapers had intimated and announced the sensational event beforehand. It was the most sought-after moment of the trial. People camped out at the courthouse the night before from all corners of Georgia and the South like diehard rock-star fans hoping for prime seats, and everyone who couldn’t make it to the surrounding area milled around dressed in suits without jackets, eager to know exactly what Leo M. Frank would say in response to each allegation made against him. But more importantly, they wanted to know the details concerning the whereabouts of Leo Frank and Mary Phagan on Saturday, April 26, 1913, noontime, because of an alleged curious inconsistency.

The Ultimate Question Wanting to Be Answered

The most important unanswered question in the minds of everyone at the trial on August 18, 1913, was: Where did Leo Frank go before the minutes between 12:05 p.m. and 12:10 p.m. on Saturday, April 26, 1913? Monteen Stover had testified she found Frank’s office empty during this five-minute time segment, and Leo Frank told Atlanta police he never left his office during that time. According to the police who took Frank to his office to check his accounting books on Sunday morning, April 27, 1913, Frank said that Mary arrived in his office at about 12:03 p.m. On Monday morning, April 28, 1913, Leo Frank, in the presence of his high-profile attorneys, made an unsworn deposition to the Atlanta Police in an interrogation room; Leo Frank said Mary came alone to his office, “Between 12:05 p.m. to 12:10 p.m., maybe 12:07 p.m.” And at the coroner’s inquest, Leo Frank was sworn under oath on May 5 and 8, 1913, and said Mary Phagan came to his office between 12:10 p.m. and 12:15 p.m. Would Leo Frank give a fourth version of Mary Phagan’s arrival time from the witness stand?

Two murder investigators testified that Leo Frank gave them the alibi he never left his office from high noon until after a quarter to 1:00 p.m. on Saturday, April 26, 1913. If Leo Frank’s alibi held up, then he couldn’t have killed Mary Phagan.

Everyone wanted to know how Leo Frank would respond to the contradictory testimony concerning his whereabouts within his timeline alibi.

Leo Frank was left to answer the question about his whereabouts on April 26, 1913, between 12:05 p.m. and 12:10p.m., because Monteen Stover didn’t collect her pay envelope until next Saturday, May 3, 1913. When the police stumbled upon Stover and her stepmother, they discovered the missing link in the murder alibi timeline of Frank.

Georgia Code, Section 1036: The Accused has the right to make an UNSWORN statement and refuse to be cross-examined at their trial.

“unsworn” definition: not bound by or stated on oath (www.memidex.com/unsworn).

Georgia Code, Section 1036

Leo Frank decided to make an unsworn statement and not allow examination or cross-examination.

No Commentary Allowed

The state’s prosecution team also understood that the law did not allow the Solicitor General Hugh M. Dorsey or his legal team counselors to orally interpret or comment on the fact that Leo Frank was not making a statement sworn under oath at his own murder trial and he would not be cross-examined by opposing team counselors.

The prosecution and defense respected this rule.

Monday, the 18th day of August, Leo M. Frank spoke on his own behalf, making an oral unsworn statement to the jury as allowed by Georgia Code, Section 1036; it did not permit any cross-examination without Leo Frank’s consent, and thus none occurred (Koenigsberg, 2011). Leo Frank was also allowed to use his handwritten notes and did not have to submit them as evidence or for review to the prosecution at the trial.

Leo Frank’s speech was carefully put together with months of preparation, and thus some of the answers to emerging questions and allegations made against him required articulated responses, explanations, retorts, and rebuttals to put things into proper perspective.

A Peculiar Thing About Liberty Is It Allows Dangerous Choices

What was perhaps most damaging to Leo Frank’s credibility is the fact that every witness at the trial, regardless of whether they were testifying for the defense or prosecution, were each sworn individually, and therefore spoke under oath, except for Leo Frank. Thus it didn’t matter if the law prevented the prosecution or defense from commenting on the fact Leo Frank refused cross examination, opting instead to make an unsworn statement, because the jury would read between the lines when all was said and done anyway. Making an unsworn statement does not suggest one is guilty, but it certainly would raise eyebrows.

Likely damaging to Leo Frank was the cultural undercurrent of the Confederate South rooted in an “honor bound” society.

With a sworn jury upholding its sacred duty, Leo Frank’s honor and integrity were put on the line and put into question as a result of what Southerners likely perceived as his cowardly decision under Georgia Code, Section 1036. Thus greater weight would naturally be given to those witnesses who were sworn under oath and spoke against Leo Frank vs. Leo Frank’s unsworn rebuttals to their statements, allegations, and claims. It put the affair under a new lens of the sworn vs. the unsworn.

One thing is certain about Leo Frank’s unsworn speech. It was an ironic lesson in the number one rule for criminals: keep your mouth shut, because sometimes the less you say the better. Not only had Leo said things that were considered grossly incriminating, but he babbled for hours about the nanoscopic pencil accounting tabulations he had done on April 26, 1913, between 3:00 p.m. to 6:00 p.m., delivered live on August 18, 1913, to show the jury he was far too busy from from 3:00 p.m. to 6:00 p.m., to have committed the murder of little Mary Anne Phagan – but the whole thing seemed contrived.

The average Southerner in 1913 was naturally asking the question: What white man would make an unsworn statement and not allow himself to be cross-examined at his own murder trial if he were truly innocent? Especially in light of the fact that the South was culturally White Racial Separatist and two major material witnesses who spoke against Leo Frank were Negroes, both employees of the National Pencil Company, one claiming Leo Frank was acting rather peculiar and one claiming to be a murder-accessory-after-the-fact and chief accuser.

In the Atlanta of 1913, African-Americans were perceived as “second and third class citizens” and less reliable than white folks in terms of their capacity for telling the truth. In 2013 and the years beyond, the average American naturally asks, Why wouldn’t Leo Frank allow himself to be cross-examined when he was trained in the art and science of debating during his high school senior year (Pratt Institute Monthly, June, 1902) and all the way through his college years, where earned the rank of Cornell Congress debate team coach (Cornellian, 1902 through 1906, Cornell Senior Class Book, 1906, Cornell University Alumni Dossier File on Leo Frank, Retrieved 2013)?

Not One, but Two African-Americans: Newton Lee and James Conley

In fact, most Leo Frank partisan authors omit the complete unabridged trial testimony of Newt Lee and Jim Conley from their retelling of the Leo Frank case. Both the former NPCo Negro employees Newton “Newt” Lee, the night watchman, colloquially known as the night watch and misspelled as “nightwitch” in contrived death notes attempting to pin the crime on him, and James “Jim” Conley, the factory custodian, had given very titillating testimony about late afternoon whoring and moving the dead body of Phagan from the bathroom area of the metal room and dumping her in the cellar. Both Negroes had made clearly damaging statements to different degrees against Leo M. Frank. The evidence Newt Lee brought forward was circumstantial, but curiously intriguing and never adequately explained by Leo Frank then or his defenders now.

Come to Work an Hour Early

Leo Frank on Friday evening, April 25, 1913, made a request to Newt Lee that he report to work an hour early at 4:00 p.m. on Confederate Memorial Day, Saturday, April 26, 1913, the reason was that Leo Frank had made a baseball game appointment with his brother-in-law Mr. Ursenbach, a Christian man who was married to one of Lucille’s older sisters. Leo Frank would give two separate and unique reasons at different times why he canceled that bromance at 1:30 p.m., Saturday, April 26, 1913, in the Selig dining room on the wall telephone. The first reason, at one time he stated he had too much work to do, and at another time, the second reason, he was afraid of catching a cold.

Normalcy and Schedules

Newt Lee’s normal expected time at the National Pencil Company factory on Saturdays was 5:00 p.m. sharp. When Newt Lee intentionally arrived at the National Pencil Company at 4:00 p.m. on Saturday, April 26, 1913, Leo Frank had forgotten, because he was in an excited state. On that fateful afternoon, Leo Frank was unlike his normal calm, cool, and collected bossman self, who would normally say, “Newt, Step in here a minute.” Instead, Leo Frank burst out of his office bustling frenetically toward Newt Lee, who had arrived on the second floor lobby at 3:56 p.m. on Saturday, April 26, 1913. Upon greeting each other face to face, “Mr. Frank” requested that Lee go out on the town and “have a good time” for two hours and come back at 6:00 p.m.

Mr. Frank, Can I Please Sleep in the Packing Room?

Because Leo Frank asked Newt Lee to come to work one hour early, Newt Lee had lost that last nourishing hour of sleep one needs before waking up fully rejuvenated. At the second-floor lobby of the NPCo factory, Lee requested to Leo that he allow him to take a nap in the packing room (adjacent to Leo Frank’s window front office), but Leo Frank reasserted that Newt Lee needed to go out and have a good time, until finally Newt Lee acquiesced and left for two hours.

At the Frank trial, Leo would state he sent Newt Lee out of the NPCo factory for two hours because he had work to do. When Newt Lee came back the double doors halfway up the staircase were locked and never had been before on Saturday afternoon. When Newt Lee unlocked the door and went to Leo Frank’s office, he witnessed his boss bungling and nearly fumbling the time sheet, when trying to put in a new one within the punch clock for the night watchman to register. The circumstances of this incident would later reveal a deliciously racist subplot in the making of the Mary Phagan murder mystery.

Business Policy

It came out before the trial, Newt Lee was told by Leo Frank that it was a National Pencil Company policy that once the night watchman arrived at the factory he was not permitted to leave the building, under any circumstances, until he handed over the reigns of security to the day watchman. NPCo security necessitated being cautious given that poverty was rife in the South, there were fire risk hazards, and the “high-tech” machinery and equipment at the NPCo was worth a small fortune in the manufacturing heart of Atlanta, 1913. Security was a matter of survival.

The two-hour time table rescheduling, canceled ballgame, corporate attendance policy rule waiver, bumbling with the time sheet, the locked double doors halfway up the staircase, and suspiciously excited behavior were interpreted by the prosecution as circumstances against Leo Frank in light of the fact the “murder notes” found next to Mary Phagan’s head, physically described Newt Lee morphologically, including his height and complexion, calling him the “night witch” when he was colloquially known at the factory as the night watch. And why did Leo Frank phone Newt Lee, not once, but two more times that evening at the factory at 7:00 p.m. and 7:30 p.m.

The substance of what happened between Newt Lee (or James “Jim” Conley) and Leo Frank from April 26, 1913, onward is most often downplayed, spun, or suffers from severe omission by Leo Frank partisan authors.

From the testimony of these two Negro witnesses, we learn of one of the most diabolic intrigues calculated to entrap the innocent Negro night watchman Newt Lee because it would have been easy to convict a Negro in a White Separatist South where the ultimate crime was a black man having not only interracial sex with a white woman, but committing battery, rape, strangulation, and mutilation right out of the book Psychopathia Sexualis (available in our library).

The Jewish-Black Racist Railroading and Framing that Failed within Forty-Eight Hours

The well-calculated plot was most exquisitely formulated; it created 2 layers of Negroes between Leo Frank and being discovered as the real murderer. It wouldn’t take the police long to realize Newt Lee didn’t commit the murder, and since the death notes were written in Ebonics, it would leave the police hunting for another Negro murderer. As long as Jim Conley kept his mouth shut, he wouldn’t hang. So the whole plot rested on Jim Conley, and it took the police three weeks to crack him using the time old third-degree method (good cop vs. bad cop).

The ugly racial element of the Mary Phagan murder subplot is rarely articulated in the context of Leo Frank, a prominent white man and Asheknazi Jewish-American in the white racial separatist South, who first tried to pin the murder of Mary Phagan on an old, balding, and married Negro Newt Lee with no criminal record to boot. And when that first racist subplot failed and was abandoned, Leo Frank changed course for the last time, and a new subplot was formulated to pin the crime on Jim Conley the “accomplice after the fact”!

If the racist Jewish gambit had played out as Leo Frank had intended, their would have likely been one or two dead Negroes in the wake of this intrigue. Because Jim Conley would have had to be crazy in the mind of the Leo Frank defense to prevent the solution to the crime being revealed. Jim Conley was scared beyond comprehension knowing what white people did to Negroes who beat, raped, and strangled white females. It wasn’t that long ago, when the Atlanta race riot erupted when four white girls were raped by Negroes in September of 1907, the white response had left two white men and two dozen Negroes dead. The body count was a rather brutal, but effective method in keeping rape statistics in check.

The Accuser Becomes the Accused

The new murder theory posited by the Leo Frank defense was that Jim Conley assaulted Mary Phagan as she walked down the stairs from Leo Frank’s office. Once Phagan arrived at the NPCo lobby of the first floor, she was robbed, thrown down fourteen feet to the basement through the two foot by two foot wide scuttle hole (located at the side of the first-floor lobby elevator), then Conley went through the scuttle hole, climbing down the ladder, dragged her to the garbage dumping ground, diagonally in front of the cellar garbage incinerator, known as “the furnace,” where he allegedly raped and strangled her, finally penning the notes in the dim light of the gas jet.

The new Jim Conley murder theory was still like something right out of the book, Psychopathia Sexualis by Krafft-Ebing, 1886.

If what Newt Lee and Jim Conley said was mostly true, then the case of Mary Phagan was an interracial double murder in the making, with a battered, raped, strangled, and mutilated thirteen-year-old White girl and an innocent Negro hanged for the crime, but this grotesque racist framing was botched by a book smart Jewish intellectual with no prescience or common sense.

What was even more odd was the conversation between Leo Frank and Newt Lee, who were intentionally put alone together in a police interrogation room at the Atlanta Police Station. The experiment was to see how much Leo Frank would interact with Newt Lee and determine if any new information could be obtained.

Leo Frank scolded Newt Lee for trying to talk about the murder of Mary Phagan and said that if Newt Lee kept up that kind of talk he and Leo Frank would go straight to hell.

Who’s the Star Witness at the Leo Frank Trial?

The Jewish community has crystallized over the last century around the notion that the Negro Jim Conley was the star witness at the trial and not fourteen-year-old Monteen Stover, who ironically defended Leo Frank’s character and inadvertently broke his alibi.

Leo Frank’s Response to Monteen Stover at the Trial

What’s rather odd is why Leo Frank revisionists and partisan authors-journalists downplay the significance of Monteen Stover’s trial testimony and Leo Frank’s ineluctable rebuttal to alibi challenging testimony on August 18, 1913, at 2:34 p.m. The Governor John M. Slaton would later play down and ignore the Stover-Frank incident in his twenty-nine-page commutation order June 21, 1915.

Would There Be a Conviction for Leo Frank without Jim Conley?

A question left unanswered is why have so many Jewish authors who write about the Leo Frank case have chosen to obscure the significance of Monteen Stover by putting all the focus on Jim Conley and then claiming without Jim Conley there would have been no conviction achieved for Leo Frank.

So the real question here is this: could Leo Frank have been convicted on the testimony of Monteen Stover without the testimony of Jim Conley?

It is a question left for speculation only, because no one ever anticipated the significance of Jim Conley telling the jury on August 4, 1913, he had found Mary Phagan dead in the area of the metal room bathroom.

It was not until Leo Frank gave his response to Monteen Stover’s testimony explaining why his second-floor business office was empty on April 26, 1913, between 12:05 p.m. and 12:10 p.m. that everything came together tight and narrow.

Tom Watson solved this issue about “no conviction without Conley” in the September 1915 issue of his Watson’s Magazine, but perhaps it’s time for a 21st century (2013) explanation to make it clear why the Georgia Supreme Court ruled more than a century ago that the evidence and testimony of the Frank trial sustained Leo’s conviction.

Closing Arguments and the Significance of August 18, 1913, Between 2:00 p.m. and 6:00 p.m.

August 18, 1913, was considered a big day – the crescendo of the trial – because during the final days of the People vs. Leo M. Frank trial, which ended on August 21, 1913, the four days of closing arguments (August 21st, 22nd, 23rd, 25th, 1913, no 24th because it was Sunday) commenced with Luther Zeigler Rosser, Frank Arthur Hooper, Reuben Rose Arnold, and Hugh Manson Dorsey.

More importantly, the timing of Leo Frank’s August 18, 1913, four hour long unsworn trial statement was significant, because it was near the tail end of his own contentious murder trial (July 28 to August 21) and exactly one week before the jury would render its unanimous verdict at 3:56 p.m. on Monday afternoon, August 25, 1913, Judgment Day.

Leo Frank Got the Last Word at the Trial

And five minutes before the end of the trial on August 21, Leo Frank spoke once more on his own behalf unsworn for five minutes, disavowing the former employees making various claims, such as he knew Mary Phagan by name, and other allegations he went into the dressing room for presumably “immoral purposes” with one of the foreladies.

Did the Jury Make the Right Decision? Now It’s Time for You to Be the Jury!

What happened on August 18, 1913, brings one forth to the single most important unanswered question over the last century by researchers, scholars, academics, southerners, northerners, lawyers, judges, courtroom staff, historians, revisionists, partisans, journalists, and most secondary source authors concerning the Leo Frank trial:

What Just Happened Here?

After mounting the witness stand on Monday, the 18th of August 1913 in the afternoon, did Leo Frank divulge what amounted to an unmistakable murder confession? Or was it just delicious irony?

Did Leo Frank possibly suggest that he might have been inside the place and at the time the murder might have occurred? (See: Brief of Evidence, 1913, pages 185 and 186 of the official trial record, Leo Frank’s response to Monteen Stover’s testimony)

To new independent scholars, observers, and researchers interested in the Leo Frank Case: Only the official stenographed Leo Frank trial testimony transcribed into the 1913 Brief of Evidence, the 2D and 3D National Pencil Company floor diagrams (State’s Exhibit A and Defense Exhibit 61), Leo Frank’s Monday, April 28, 1913, statement to the police, known as State’s Exhibit B and an honest-open mind without self-deception, answer the August 18, 1913, Leo Frank murder trial confession question definitively.

Are You Ready?

Commonsense and being able to read between the lines can answer all of these questions henceforth and definitively.

Does the so-called admission that amounted to Leo Frank Murder Confession #3 sustain Leo Frank Murder Confession #1 to Jim Conley and Leo Frank Murder Confession #2 to Lucille Selig Frank (State’s Exhibit J, 1913), and finally was there a fourth Leo Frank murder confession made outside of the official court records? Let’s find out.

Leo Frank Murder Confession Number Three

The “Leo Frank Murder Trial Confession” allegedly occurred on August 18, 1913, between 2:00 p.m. and 6:00 p.m., which some postulate, was the third of three known Leo Frank murder confessions revealed by the official trial record, exhibits, and evidence, which became an integral part of the brief of evidence, 1913. The fourth Leo Frank murder confession is outside the official record, but where is this evidence?

3

The third Leo Frank murder trial confession made on August 18, 1913, at 2:34 p.m. was interpreted, threaded, and articulated by the two state’s prosecution team lawyers, the Solicitor General Hugh Manson Dorsey for the Atlanta Circuit and Special Assistant Solicitor Frank Arthur Hooper, together, both of these men as part of their closing arguments (Closing Arguments Leo Frank Case, American State Trials, Volume 10, 1918, John D. Lawson LLD; August 22, 23, & 25, 1913, Arguments of Hugh M. Dorsey, published in 1914) put the solution to the Mary Phagan murder mystery in language the jury could understand, but could they have been mistaken about Leo Frank’s guilt?

Was There a Fourth Leo Frank Murder Confession outside the Three Leo Frank Murder Confessions Located within the Official Record? Yes.

Leo Frank during an interview concerning seventeen questions and answers published by the Atlanta Constitution on March 9, 1914, would reaffirm the Leo Frank August 18, 1913, 2:34 p.m., newfangled admission (AJC, March, 9, 1914).

Tom Watson’s Inferno

Firebrand attorney Tom Watson in 1914, 1915, 1916, and 1917, through his newspaper, The Jeffersonian, and his Watson’s Magazine (August and September, 1915), does a superb job of articulating that Leo Frank’s possible solution to the Mary Phagan murder is provided, without Jim Conley’s testimony in the September Issue (The Official Record in the Case of Leo Frank, A Jew Pervert, Watson’s Magazine, 1915).

13 to 0?

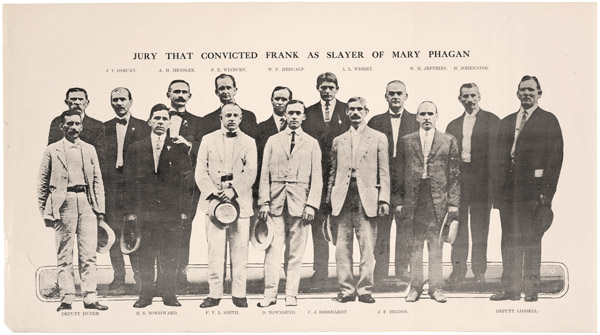

Some would postulate the Leo M. Frank trial admission was ultimately interpreted and acknowledged as incriminating, because unanimously the empaneled thirteen-man-collective-mind, made up of the presiding Honorable Judge Leonard Strickland Roan and the petite trial jury of twelve white men, together voted unanimously 13 to 0 against the defendant, not only giving him a verdict of guilty, but unanimously they voted again 13 to 0 for “without mercy” in sentencing Leo Frank to death. Not one, but two decisions were made unanimously.

The Judge Leonard Strickland Roan Gave the Jury Two Options “With” or “Without Mercy”

If there was any doubt of Leo M. Frank’s guilt, the 12-man jury and Judge Leonard Strickland Roan could have sentenced Leo rank to life in prison, instead of sentencing him to death by hanging. When the Jury unanimously sentenced Leo Frank to death by hanging after deciding on a verdict of guilt, the Judge Leonard Strickland Roan, had the legal option to downgrade the jury’s death sentence, and only give Leo Frank life in prison – that is if Roan disagreed with the judgment – but Roan agreed with their collective verdict and recommendation without mercy.

The Jewish community and Leo Frank revisionist authors have suggested Judge Leonard Strickland Roan doubted the verdict of Leo Frank in one of his appeasing comments made orally to his former law partner Luther Rosser, but if Roan actually doubted the verdict, he could have given Leo Frank a new trial.

You Are Hereby Sentenced to Be executed by Hanging on April 17, 1914, Happy Birthday

Certainty of Leo Frank’s guilt was so strong after reviewing his trial testimony for months that he was ultimately re-sentenced by judge’s orders to die on his thirtieth birthday, April 17, 1914. Only absolute mathematical certainty of guilt warrants such a cruel sentencing date by a judge.

What Were the First Two of Four Leo Frank Murder Confessions?

Leo Frank Murder Confession Number One: The Jim Conley Affair

Question #1: Was the first Leo Frank murder confession delivered to James “Jim” Conley (James Conley, Brief of Evidence, August, 4, 5, 6, 1913) at the factory on Confederate Memorial Day, Saturday, April 26, 1913? Or is Jim Conley lying about Leo M. Frank confessing to him about murdering Mary Phagan (BOE, Leo Frank Trial Statement, August 18, 1913)?

It took the police weeks of interrogation and three affidavits to get Jim Conley to finally tell the ugly truth of what happened on that infamous day, but did he tell everything?

See: James Conley, Affidavits, May, 1913 and Trial Testimony, Brief of Evidence, August, 1913.

Brief of Evidence Testimony of Jim Conley: http://www.leofrank.org/jim-conley-august-4-5-6/

Leo Frank Murder Confession Number Two: The Minola McKnight Affair

Question #2: Was the second Leo Frank murder confession given that same Saturday, April 26, 1913, to Lucille Selig Frank, in the late evening, once the married couple was inside their bedroom on the second floor at the Selig residence of 68 East Georgia Avenue, Atlanta, GA?

See: Minola Mcknight, State’s Exhibit J, June 3, 1913 and also the cremation request in the 1954 Notarized Last Will and Testament of Lucille Selig Frank, she passed away from a broken heart on April 23, 1957.

Leo Frank’s wife requested to be cremated, instead of buried next to her husband in the empty grave plot #1 (official real estate location id: 1-E-41-1035-01) reserved for her at the Mount Carmel Cemetery. Does this tend to sustain Minola Mcknight’s State’s exhibit J (see: BOE, State’s Exhibit J, June 3, 1913)?

How about Lucille’s request to have her ashes spread in a park in Atlanta (Oney, 2003), instead of buried or spread near her husband in the Mount Carmel Cemetery, does that sustain States Exhibit J?

Three Total Leo Frank Murder Confessions?

Question #3: To answer the question of whether or not the surviving records indicate Leo Frank made three separate murder confessions, one should start with deeply evaluating the third Leo Frank murder confession, which was given by Leo M. Frank on Monday, August 18, 1913, at his capital murder trial to the Judge and Jury.

See: Leo Frank’s Trial Testimony and his Response to Monteen Stover’s Testimony: Leo Frank Trial Statement, August 18, 1913 and Leo M. Frank Brief of Evidence, Murder Trial Testimony and Affidavits, 1913. After comparing Monteen Stover’s testimony to Leo Frank’s trial statement, see if you can figure out the solution to the Mary Phagan murder mystery. If you need a little bit of help, read the Atlanta Constitution Issue March 9, 1914 (Leo Frank Answers List of Questions Bearing on Points Made Against Him, March 9, 1914).

Start with Leo M. Frank Murder Confession #3 before we review Leo M. Frank Murder Confession #2 and #1.

Does the March 9, 1914, Atlanta Constitution Leo Frank interview article count as Leo Frank murder confession #4? Are there really four Leo Frank murder confessions? Start with #3.

Monteen Stover vs. James “Jim” Conley

For the last century, people who take the side of Leo Frank and the ditto head position of the Jewish community since 1913 to present and “Frankites” (Leo Frank Tribal Cult Members) assert as a united front that Jim Conley was the star witness who largely convicted Leo M. Frank. Monteen Stover is downplayed, spun, or omitted with a self-deception that requires psychological evaluation.

Was Jim Conley really the star witness, or was it Monteen Stover?

Why do Frankites avoid talking about State’s Exhibit A and B, comparing them against the trial testimony of Monteen Stover and Leo M. Frank’s trial statement response to her testimony that he delivered on August 18, 1913?

What does the depth of the official record reveal?

Can the 318 page Leo Frank Brief of Evidence be distilled down to reveal Leo Frank’s guilt or his railroading?

The Depth of the Leo Frank Trial Reduced to Its Nexus

Twenty-first-century Leo Frank scholars who have read and studied more than 3,000 pages of the surviving official records in the case understand everything can be reduced to the “Trinity” (no religious reference applies here).

The Trinity Is the Solution to the Mary Phagan Murder Mystery: Monteen Stover’s Testimony + State’s Exhibit B + Leo Frank Trial Testimony Response to Monteen Stover Suggests the Mary Phagan Murder Mystery = Solved!

If there are any doubts about this trinity, the icing on the cake is in the March 9, 1914, Atlanta Constitution issue where Leo Frank makes his fourth murder confession — the March 9, 1914, Leo Frank jail house murder confession.

That’s the tight and narrow of it, when you boil down to its essence, more than 3,000 pages of official legal documents. Everything comes down to the word of Leo Frank vs. the word of Monteen Stover, not the word of Leo Frank vs. Jim Conley.

Jim Conley was disputably an accomplice, and the testimony of an accomplice is not enough to convict under the law. But did all the evidence taken together convict Leo Frank instead?

Stitched Together…

See, the original State’s Exhibit B:

Part 1 – http://www.leofrank.org/images/georgia-supreme-court-case-files/2/0061.jpg

Part 2 – http://www.leofrank.org/images/georgia-supreme-court-case-files/2/0062.jpg

Complete Analysis of State’s Exhibit B (required reading): The full review of State’s Exhibit B

Meditate on the 2- and 3-Dimensional Floor Plan of the NPCo Second Floor. Please Review These National Pencil Company Factory Diagrams.

The National Pencil Company in Three Dimensions

Three-Dimensional floor plan of the National Pencil Company in 1913: http://www.leofrank.org/images/georgia-supreme-court-case-files/2/0060.jpg.

The Defendant Leo Frank’s Factory Diagrams Made on His Behalf

Two-Dimensional floor plan of the National Pencil Company in 1913. Defendants Exhibit 61, ground floor and second floor 2D bird’s-eye view maps of the National Pencil Company: http://www.leofrank.org/images/georgia-supreme-court-case-files/2/0125.jpg. Plat of the First and Second Floor of the National Pencil Company.

1. State’s Exhibit A (Small Image) or State’s Exhibit A (Large Image).

2. Different Version: Side view of the factory diagram showing the front half of the factory

3. Bert Green Diagram of the National Pencil Company

Indisputable Acknowledgment Number One Is Based on the Factory Diagrams: The only set of toilets on the second floor are located inside the metal room (State and Defendant Exhibits, 1913), so one has to pass through the metal room to its far corner to reach the toilets. The only toilets are physically inside the metal room.

Three Viable Possibilities

Questions:

Did Mary Phagan go to the toilets in the metal room to use the bathroom? Or did Mary Phagan go into the metal room to find out if the brass sheets had come in? Did Mary Phagan have a rendezvous with Leo Frank in the metal room?

Walk with Leo Frank across the Second Floor from His Inner Office to the Metal Room Where the Bathroom Is Located

As a response to Monteen Stover’s trial testimony, does Leo Frank in essence “unconsciously” describe himself walking from his second-floor inner office, through his adjacent outer office, into the hallway, then down the hallway, through the door, into the metal room with his “unconscious bathroom” (BOE, 1913) visit to the only bathroom on the second floor, which is located in the metal room?

The Ultimate Blunder

Observers are wondering if Leo Frank lost his mind in placing himself in the very place the prosecution spent a month trying to convince the jury where the murder of Mary Phagan had occurred and ultimately between the time frame of 12:02 p.m. and 12:19 p.m.? Observers ask this because Leo Frank told the seven-man panel lead by Coroner Paul Donehoo and the six-man jury of the coroner’s inquest that he (Leo Frank) did not use the bathroom all day long, not that he (Leo Frank) had forgotten, but that he had not gone to the bathroom at all.

The visually blind prodigious savant Coroner Paul Donehoo with his highly refined bullshit detector was incredulous as might be expected. Who doesn’t use the bathroom all day long? It was as if Leo Frank was mentally and physically trying to distance himself from that place at the far corner of the second floor in the metal room.

Why Is the Leo Frank Murder Confession Question Important?

The importance of asking if Leo M. Frank made what amounts to a murder confession is an honest and genuine one. Inexplicably, no one has touched this question since the two-year drama between 1913 to 1915 unraveled, and it is hoped that beyond 2013 with the centennial of the Mary Phagan murder, every contemporary writer would broach the subject of the August 18, 1913 “Leo Frank murder trial confession question” and comment on it after avoiding it for one hundred years. Alas, the likelihood is slim to none that people will finally address Leo Frank’s four separate and distinct murder confessions, because the majority of people who produce works and treatments on the Leo Frank trial are either Jews or members of the Cult of Leo Frank, known as the Frankites, which includes Gentiles.

The Bottom Line: Can the “Question” Be Answered by the Official Record?

We will address and articulate the most significant murder confession among Leo Frank’s four murder confessions here and now, in full, and hope the word gets out. Leo Frank made an unmistakable murder confession on August 18, 1913 at his own capital murder trial that he strangled Mary Phagan in the metal room on April 26, 1913, based on a commonsense interpretation of the official record, 1913.

The Leo Frank Murder Confession vs. Leo Frank Was Scapegoated

The Leo Frank confession question is one that has puzzled scholars for more than a century and fair-minded observers are wondering why Leo Frank partisans, the Jewish community, Jewish writers and film producers, and other Leo Frank activists keep dodging and avoiding the Leo Frank murder confession question that his testimony suggests since it was first delivered Monday afternoon on August 18, 1913, between 2:00 p.m. and 6:00 p.m.

Anti-Gentile Blood Libel Smear Campaign

From the Southerner perspective, instead of discussing the Leo Frank confession question, Jews and Leo Frank partisans unilaterally resort to defaming the descendants of European-Americans with what amounts to unsubstantiated anti-Gentile blood libel, false accusations of conspiracy and scapegoatery. Some anti-Semitic Southerners think Jews are trying to instigate another civil war between Jews and Gentiles, because the bigoted anti-Gentile smears still continue unabated to this very day.

One Hundred Years of Hate in the Context of Millennial Long Tribal War, Rebuked

For one hundred years the Jewish community has been unraveling an unrelenting cultural and race war against Gentiles with the accusation of collective guilt, to wit: that collectively European-American pervasive anti-Semitic bigotry and prejudice unilaterally inspired the anti-Jewish railroading, framing, conviction, and assassination of an innocent Jew named Leo Max Frank, the B’nai B’rith president of Atlanta through the years 1913 to 1915.

Jewish-Gentile Tensions Smoldering Beyond Smears to a Final Global Conflict?

Even the average observer is wondering if these loud and lopsided century-old anti-Gentile smears made against European-Americans, coming from the Frankite side of the Leo Frank case, are part of a wider historical blame game by Jews against Gentiles. The Leo Frank case has become another example of the unforgivable instigation and antagonization of conflict by Jews against Gentiles that remains mostly unchallenged today.

5,800 Years of International Jewish Cultural Terrorism Reaching a Boiling Crescendo

For European-Americans, the Leo Frank case is not a Jewish-Gentile conflict, but a grisly murder case involving an infatuated boss who is high functioning despite some serious psychological, behavioral, and emotional problems “hidden under the surface,” who couldn’t handle rejection and felt frustrated, spurned, and thus became more aggressively persistent to the point of violent rage.

Jews are stacking up the fabricated pathological lies about the Leo Frank case, using the case as part of their wider culture war against Gentiles and Western Civilization. It is artificially turning up the heat concerning Jewish-Gentile tensions, which could lead to another boiling crescendo of World War II magnitude.

Not Even the Most Prominent Frankite Would Even Dare Broach the Subject

The Leo Frank scholar Steve Oney, the seasoned tabloid virtuoso and Jewish Frankite Cult Rock Superstar, does not even dare to address the “Leo Frank Confession Question” in his myopic, long-winded, egoist, and pretentiously biased but well written 2003 book, And the Dead Shall Rise: The Murder of Mary Phagan and the Lynching of Leo Frank.

Back to the Ignoring of the Leo Frank Confession Question by Frankites

Observers are wondering why no contemporary Frankite (Leo Frank partisan) writers have ever analyzed or offered their new spin on this very reasonable “Leo Frank Confession Question”? Why won’t they even peep a single word about it?

Answer:

It might be wasteful for any contemporary writer in the Frank partisan camp to touch the Leo Frank murder confession subject, as it would wipe out a century long racist blame game by a large and vocal segment of the Jewish community, which is ultimately a defamation campaign perpetuating the Leo Frank anti-Semitic blood libel hoax for more than one hundred years.

From the Prosecution Side of the Equation – The Age of Enlightenment: 2012 and Beyond. Thank Goodness for the Internet.

The Leo Frank anti-Semitism hoax came to its end with the centennial of the strangulation of Mary Phagan between 2013 to 2015 as the Leo Frank subject went viral and more people reviewed the primary source materials than ever before in the history of the case. It is hoped that the smears and slanders directed at Hugh M. Dorsey, Southerners, and European-Americans as a collective will eventually die off, or there is likely to be an exacerbation of fighting words and increased conflict between Jews and Gentiles between 2013 and 2015.

The Last Man to Articulate the Leo Frank Murder Confession

The last man with enough fiery brass to address this question superbly was the ginger-headed genius Tom Watson in 1915, published through his Jeffersonian Publishing Company in Watson’s Magazine 1915 issues January, March, August, September, and October and his 1914 / 1915 newspaper, The Jeffersonian (Watson, 1914 & 1915). Before Watson, Hugh Dorsey and Frank Arthur Hooper in late August 1913 both threaded and incorporated the Leo Frank murder confession as part of their long closing arguments (American State Trials Volume X 1918, “Closing Arguments of Hooper and Dorsey August 1913”).

The Best Articulation of the Leo Frank Murder Confession

Tom Watson does not get original credit for making this analysis about Leo Frank’s statement being a murder confession, but he does articulate it better and more colorfully than Mr. Hooper and Hugh M. Dorsey. True or False?

Compare the three men’s analysis by reading: Argument of Hugh M. Dorsey, followed by The Argument of Mr. Frank Hooper where they both elucidate in their final closing arguments what sounds like a near confession being made by Leo M. Frank. Compare Hugh M. Dorsey’s and Mr. Hooper’s articulations of Leo Frank’s bathroom statement together against Tom Watson’s version published August and September 1915 in Watson’s Magazine. It reveals this case centers around Monteen Stover more than it does James Conley.

Which Closing Argument Is More Convincing Neutral Observers? The Closing Argument of Dorsey or Hooper? How Does Former U.S. Senator and Attorney Tom Watson’s Post-Trial Testimony Analysis?

A POWERFUL Historically Significant Question Emerges from the Testimony of Leo Frank

One hundred years after Leo Frank gave his trial testimony on August 18, 1913, dispassionate researchers, revisionists, and neutral scholars who meticulously studied the Leo Frank case began asking a much grander scale and historically intriguing question:

How many times in United States history has the prime suspect and defendant made what amounts to a virtual confession at their own capital murder trial?

This question has never been publicly asked before until here and now.

Don’t take our word on it…

Independent Reader: Can You Solve the Leo Frank Confession Equation with the Trial Testimony?

Let’s begin with opened minds.

The Detailed Approach to the Leo Frank Murder Confession, August 18, 1913:

First

Before first independently undertaking the task and then answering the Leo Frank murder confession question, one must be familiar with several elements of the official record. One must first read Leo Frank’s State’s Exhibit B. Pay special attention and note the time Leo Frank said Mary Phagan had arrived at his office. State’s Exhibit B is concerning a lawyer and police witnessed, stenographer captured, statement made on the morning of Monday, April 28, 1913, by Leo M. Frank about Mary Phagan entering his office between 12:05 and 12:10, with a “maybe” 12:07.

Nothing about a bathroom visit is mentioned in State’s Exhibit B or the inquest testimony given by Leo Frank, but it is finally revealed at the trial after Monteen Stover, the Star Witness, gives her testimony. Even more startling is Leo Frank told the inquest that he did not use the bathroom all day, not that he forgot, but that he didn’t use it. He was trying mentally and physically to keep himself away from that side of the building on his floor.

Second

Read and study the trial statement of Monteen Stover, about her arriving in Leo Frank’s inner and outer office at 12:05, looking for him and waiting for him for five minutes based on the big clock on the wall in Leo Frank’s office, until she eventually left at 12:10; followed by the testimony of Leo Frank defense witness Detective Harry Scott, then the Assistant Superintendent of the Pinkerton Detective Agency. See: Leo Frank murder trial testimony for both statements (BOE, 1913).

Third

Then read the Leo M. Frank Murder Trial Testimony, where Leo Frank says two intriguing things to counter the testimony of Monteen Stover as he slips in two interesting defenses. First, Leo Frank does not mention seeing Monteen Stover in his office or at all, and pay close attention to what Leo Frank then explains where he might have “unconsciously” gone on the second floor of the National Pencil Company between 12:05 to 12:10 as the reason he was not seen by Monteen Stover in his office. Second, Leo Frank says the reason 5’2″ tall Monteen Stover couldn’t see him [Leo Frank] in his inner office was that the door on his four-foot tall safe was opened and thus blocked off the view to in the inner office. When Leo Frank stated the four-foot tall safe door was open all day, why would 5’2″ tall Monteen Stover be the only person to not see Leo Frank or go into his inner office? Especially in light of the fact that she was there for her pay envelope.

Both the “unconscious” bathroom visit and safe door explanations were newfangled revelations on August 18, 1913, for the purpose of creating two possible alibis countering 5’2″ tall Monteen Stover’s testimony concerning Leo Frank’s whereabouts between 12:05 and 12:10.

Both of Leo Frank’s counter defenses, “the safe door” and the “unconsciously” going to the bathroom in the metal room were shocking revelations because one put him at the scene of the crime and the other was a complete fabrication. Monteen Stover was motivated and wanted her pay, and the defense or prosecution never disputed this. Thus Stover checked both of Leo Frank’s inner and outer offices, watching the time on the clock in Leo Frank’s empty inner office from 12:05 p.m. to 12:10 p.m., on April 26, 1913.

Monteen Stover even said, she looked down the hallway and saw the door to the metal room shut. Frank was presumably on the other side of that shut door finishing off Mary Phagan.

Fourth

If you need even more help in solving the Leo Frank confession question, see what prosecution team members Hugh Dorsey and Frank Hooper have to say about Leo Frank’s “unconscious” bathroom admission (The August 1913, Argument of Hugh M. Dorsey, Published 1914; The August 1913, Frank Arthur Hooper, Closing Arguments, American State Trials Volume X, Published 1918).

In other words, start by first seeing if you can connect the dots between these three people: Harry Scott, Monteen Stover, and Leo Frank, via their own official trial testimony and statements. Be sure to see State’s Exhibit B when doing your analysis.

If you want more definitive explanations of the Leo Frank murder confession question, add two more people at the trial to help articulate it, Hugh Dorsey and Frank Arthur Hooper, that is, if you need five people (Dorsey, Hooper, Harry Scott, Monteen Stover, and Leo Frank) to help you make a stronger connection than the three witnesses alone.

If you want to save time, you can read the best analysis ever written on the Leo Frank case. Tom Watson’s reviews of the case provide the best analysis; they are published in Watson’s Magazine August and September of 1915. You should also read Tom Watson’s The Jeffersonian newspaper 1914, 1915, 1916, and 1917; they also provide excellent analysis along with his Watson’s Magazine.

Closing Arguments August 1913

Prosecution team leader Hugh Dorsey and prosecution team member Mr. Frank Arthur Hooper would interpret in their closing arguments, the exact words Leo Frank said during the specific exultation in his testimony, as being a strong admission of guilt, but they were both careful to not focus too much on it or give it too much emphasis, but instead bring every point of evidence together to concatenate the circumstantial chain of evidence around him invincibly. The strategy of the State’s prosecution resembled “death by a thousand wounds,” rather than a single death blow, even though the Leo Frank virtual murder confession amounted to suicide during his trial.

In total, more than a dozen impartial men, half of them juryman and the other half judges, from 1913 to 1915, all called to review the case affirmed the guilty verdict of Leo Frank, by not disturbing it, and they certainly didn’t miss the Leo Frank murder confession either.

“The Lone Jurywoman”

Lucille Selig’s will notarized and registered with the Government of Atlanta in 1954 (The Will of Lucille Selig Frank, 1954) specifies she wanted to be cremated, instead of being buried next to Leo Frank, who is buried in (Stern-Frank plot #2) at the Mount Carmel Cemetery in Queens, NY. Sadly, Stern-Frank plot #1, which was reserved for Lucille Selig Frank, is still empty today. It was a smidgen odd given how faithful she was to Leo Frank during the appeals, but tends to add another powerful undeniable vote of guilt against Leo Frank by the only “Jurywoman,” Lucy Selig Frank. The cremation tends to vindicate or sustain Leo Frank murder confession #2 known as State’s Exhibit J (Minola McKnight, June 3, 1913).

Fifth

Tom Watson’s Fire and Brimstone Articulation

If you don’t want to read 3,000 pages of the Leo Frank appeals records available on this web site and want a better understanding or intelligent historical perspective of the Leo Frank murder confession, you can also read Watson’s Magazine‘s five issues that cover the Leo Frank trial within the January, March, August, September, and October of 1915. The “unconscious” bathroom visit is also covered in some of the issues of The Jeffersonian newspaper as well 1914 to 1917. To cut to the chase though, skip Watson’s Magazine Jan and March 1915. The issues that cover the Leo Frank murder confession the best are the August and September issues of Watson’s Magazine in 1915 – start there.

The Most Shocking Blunder in the Leo M. Frank Trial

How It All Began in More Specific Details: SOME PEOPLE COMPLETELY MISSED IT!

On August 18, 1913, Leo Frank mounted the witness stand at his murder trial, and while giving testimony to the court and jury, throughout his half-chronological, half-rambling, and mind-numbing four-hour speech, he revealed the solution to the Mary Phagan murder mystery. It was revealed like this: After putting the courtroom to sleep during his Bueller-Bueller-Bueller Bueller-Bueller-Bueller (Ferris Bueller’s Day Off) speech, like a fox man, he snuck in some specific statements about his “unconscious” whereabouts in the shuttered and nearly empty pencil factory during the time frame of the Mary Phagan murder. But he was careful not to be too tight and narrow, so he softened it by widening the time spectrum on it. However, he also made another mistake to explain why Monteen Stover did not see him with a supposed safe door blocking his view. The two explanations were shocking.

It was the first time in all of his numerous statements that he revealed his “unconscious” whereabouts after noon on 4-26-1913. Although the average Joe Cracker and Sally Whitebread might have missed the slipped-in testimony, it absolutely wasn’t overlooked by the lucid prosecution team members, who made a point to articulate it in their closing arguments as a single thread woven amongst numerous other threads into a hangman’s noose. The prosecution’s closing arguments were remarkable, being presented on a silver platter to the conscientious judge and highly attentive jury.

High Society

The Leo Frank murder confession was not missed by the social and political elite, the highest legal minds of Georgia who were incensed by the illegal shenanigans and black-handed tactics of the bribery scandals created by the Frank defense team, unraveling from 1913 to 1915.

The upper strata of Georgia would respond to Leo Frank defense team’s successful bribery efforts, extensive witness tampering, and chicanery by finally orchestrating one of the most nervy and ballsy commando raids. It has been described as one of the most audacious prison breaks in U.S. history and thus de facto overturning John M. Slaton’s toady and cronyesque commutation.

The elites of Georgia delivered hanging justice for Leo Frank in favor of the jury, who consciously chose the determination of guilt without recommendation of mercy. The jury collectively and specifically voted for a hanging as the just payment of the guilty verdict, in other words. In the eyes of the prosecution, the jury was ultimately vindicated by the aristocratic minds of high society Marietta and Georgia.

Take off the Blinders, Frankites

True modern Leo Frank scholars didn’t miss the confession either and are now asking Frankites, “How about it?”

Now Test Your Intuitive and Detective Mind

Take a deep breath and read the trial testimony of Leo Frank and see if you can figure it out yourself, before referring to Dorsey, Hooper, and Watson. However, if you can’t figure it out on your own without Dorsey, Hooper, and Watson, keep reading here for the deeper analysis and details, and then check the original sources of the Leo Frank case on your own to confirm their veracity.

Frank Arthur Hooper Made His Final Closing Argument before Dorsey in Late August 1913

In the concluding days, Mr. Frank Hooper of the Leo Frank prosecution team in his final closing argument would suggest to the jury that Frank’s statement about an “unconscious” bathroom visit was the first time Frank mentioned it (Frank denied using the bathroom previously at the coroner’s inquest). Hooper asserted, Frank’s statement put him on the other side of the building, directly in the metal room where the bathroom was, the alleged area of the crime scene (Hooper, August 1913).

Frank Arthur Hooper was indeed correct, because Leo Frank told Harry Scott, witnessed by another police officer name Black, that he [Leo Frank] was in his office every minute from noon to half past noon, and in State’s Exhibit B. Leo Frank never mentions a bathroom visit all day, which seems odd. At the coroner’s inquest, Coroner Paul Donehoo was incredulous as he should have been that Leo Frank claimed he had not used the bathroom at all that day. It was unbelievable and raised red flags.

An Excerpt from Mr. Hooper’s Final Argument

There was Mary. Then, there was another little girl, Monteen Stover. Frank never knew Monteen was there, and Frank said he stayed in his office from 12 until after 1, and never left. Monteen waited around for five minutes. Then she left. The result? There comes for the first time from the lips of Frank, the defendant, the admission that he might have gone to some other part of the building during this time, he didn’t remember clearly. (August, 1913)

The other part of the building Mr. Hooper was referring to was the metal room, which was just down the hall from Leo Frank’s office and the place that all the evidence suggests Mary Phagan was really murdered. Review the original references listed below and make your own conclusion about whether Frank was guilty or not.

Analysis of Hooper

Indeed, for the first time in three months, it was only after Monteen Stover said Leo Frank’s office was empty from 12:05 to 12:10 when she went to collect her pay on April 26, 1913, that Leo Frank came up with his “unconscious” bathroom visit to the metal room.

What was so shocking about the metal room bathroom revelation was that Leo Frank had more than three months to prepare a statement for the court and jury, and for the first time at the trial, he mentioned an “unconscious” bathroom visit to the place the prosecution had spent four months building a case trying to prove the metal room was the REAL scene of the crime (not the basement where Mary had been dragged and dumped).

The virtual murder confession left people who had hoped for a good fight scratching their heads, wondering why Leo Frank would “tip his hand” and drop a such a bombshell spoiler, by say something so ineluctably and irreversibly incriminating at the trial.

It was an a let down. After all, everyone was hoping for a good fight. Not even Frankite spin could re-engineer this ugly debacle Leo Frank unveiled with remarkable stupidity, so the Frankites simply ignore it, knowing 99 times out of 100 the average person will never take the time to read and study the official record known as the 1913 Leo Frank Trial Brief of Evidence.

Tom Watson’s “Frank Entrapped Himself Beyond Escape”

Tom Watson would describe Frank’s “unconscious” metal room bathroom revelation, colorfully saying Frank had implicated and entrapped himself BEYOND ESCAPE (Watson, Sept 1915). Watson, like most legal observers, considered it an inescapable confession that Leo Frank murdered Mary Phagan in the metal room, because Frank by his own words put himself in the metal room toilet during the approximate time span of the murder. More specifically, Frank stated Mary Phagan was in his office between 12:05 and 12:10, maybe 12:07 on Saturday, April 26, 1913 (State’s Exhibit B, 1913). Most observers could easily consider the “Maybe 12:07” in State’s Exhibit B as the moment Leo Frank was sure Mary Phagan was dead or that she took her last breath, because the words rung vividly indicating an engram of exultation and truth. If Frank said in State’s exhibit B that Mary arrived between 12:05 and 12:10 and that he was “unconsciously” in the metal room bathroom in response to Monteen Stover’s testimony, it created the most tight and narrow admission of guilt possible without outright coming out and admitting it in a full confession.

Leo Frank Murder Confession August 18, 1913? Yes, No, or Maybe? None of the Above?

What about the other side of the Leo Frank confession question? Let’s give Leo Frank the “benefit of the doubt.”

Though to be fair, the original confession question itself sounds loaded, like it presumes Leo M. Frank made a near confession about murdering little Mary Phagan. The confession or near confession is one interpretation by three published principles and attorneys, Dorsey (Argument of Hugh M. Dorsey, 1914), Hooper (American State Trials Volume X, 1918), Watson (The Jeffersonian, 1914, 1915; Watson’s Magazine, 1915). Others might interpret it as just a harmless visit to the bathroom in the metal room at about the same time the murder occurred. In fact, Leo Frank might have been in the bathroom in the metal room while Phagan was being killed on the first floor by Jim Conley.

The only problem with the Jim Conley murder theory is that there is little to no evidence to support it, and Leo Frank made a blunder saying Lemmie Quinn came to his office at 12:20, making such an attack on the first floor impossible unless Lemmie walked in on it. At the trial Leo Frank changed his story and said Mary Phagan arrived in his office ten to fifteen minutes after his stenographer left at 12:02, putting Mary Phagan’s arrival at his office from 12:12 to 12:17 (his fourth different version of her arrival), and her staying in his office for two minutes meant she should have nearly bumped into Lemmie Quinn.

The Lemmie Quinn revelation made the murder on the first floor hard to believe without Quinn walking in on it. Most historians, though, think the Lemmie Quinn revelation was likely a lie and a blunder. What made the first floor “Jim Conley theory” even less plausible is the fact Leo Frank was less than thirty-five feet away, so he would have certainly heard a scream in the silent building.

Making Matters Worse

The Leo Frank defense only made a confusing halfhearted attempt to blame Jim Conley at the trial that came off as insincere, insecure, half-baked, hokey, and desperate. True or false? What does the official record say concerning the failed blame Jim Conley attempts by the defense team, which was partly abandoned and changed through the trial for a different version of events, making it seem phony and disingenuous? The defense version of the murder will be discussed in greater detail in another section of the Leo Frank web site.

The Defense Version of the Murder

The Leo Frank defense team would claim Mary Phagan was murdered when she went downstairs to the highest traffic point in the factory, the front entrance. In their version, Mary Phagan was accosted by the sweeper Jim Conley for her paltry $1.20 so he could buy booze — a pretty good plausible attempt — but there is one problem with it. Why would Jim Conley be waiting around in the factory all morning long when he was paid $6 the evening before? Shouldn’t he have been at the bar drinking 15 cent pitchers or 5 cent pints of beer?

Zero Evidence on the First Floor

Since the police found no blood or evidence of such a struggle near the entrance or first floor lobby, because it was the highest traffic spot in the factory and Jim had been sitting there all morning according to Alonzo Mann, and other people had seen him sitting there during the late morning like Mrs. White, it was more likely that Leo Frank asked Conley to be his look out, rather than Conley had come to work to rob factory employees. It was more likely the truth that Jim Conley was called to come to work by Leo Frank, who would have the factory all to himself in the afternoon and would need a look out for his usual Saturday whoring. Something else happened instead on that infamous April 26, 1913.

The defense also suggested Jim Conley dumped Phagan’s body down the scuttle hole, and if that were the case, her 120 lb. body would have hit the ladder all the way down during the 14 ft. drop and would have broken, bruised, cracked, or bled on the ladder – the autopsy showed no indications of a 14 ft. fall against a ladder. The other problem with the scuttle hole theory was that there were drag marks noted coming from the front of the elevator shaft leading to the pile Mary had been dumped onto, and there s no record of evidence showing Phagan had any broken or cracked bones bruises from that kind of fall either (elevator shaft fall). Phagan would have at least bruised. The defense then abandoned the scuttle hole dump theory and claimed Conley threw her down the elevator shaft. There were no bruises to indicate she had been thrown down the elevator shaft, and if she had, why didn’t she land on Steve Oney’s “Shit in the Shaft”?

Defense Version

National Pencil Company Factory Diagram 1, 1913

National Pencil Company Factory Diagram 2, 1913

Stages of the Defense Version of the Mary Phagan Murder

The Leo Frank Case Open or Closed?

When did Mary Phagan Arrive and When Was She Killed?

According to Leo Frank, the answer is sometime between 12:02 and 12:17. At different times, he said Mary Phagan arrived: 12:02, 12:03, 12:05 to 12:10, maybe 12:07, or 12:12 to 12:17, or 12:02 to 12:03. Which answer of Leo Frank’s do you believe? He gave more than four during different times in total concerning when Mary Phagan stepped into his office. Immediately after the murder, the time Leo Frank gave was very close to noon, minute or two after noon, but as time went by, the arrival time moved away from noon toward a quarter after noon and more.

Time Shift Summary of Leo Frank

On Sunday, April 27, 1913, Frank told police officers that Mary had arrived in his office at about 12:02 to 12:03. Monday, April 28, 1913, it turned into 12:05 to 12:10, maybe 12:07. At the coroner’s inquest jury, it became 12:10 to 12:15, and at the murder trial, when Frank made a four-hour statement to the jury, it would be 12:12 to 12:17. For some reason, the time shift seems to be away from the time it most likely really happened to a much later time.

Who Received the Different Versions?

Leo Frank had given numerous and different accounts of when Mary Phagan had arrived at his second floor office to: Detective Black; Chief of Detectives Newport A. Lanford; Defense witness Detective Harry Scott of the Pinkerton Detective Agency; the seven men of the coroner’s inquest jury; and lastly the murder trial jury of thirteen men (judge + twelve jurymen).

Let’s Review: What Do the Following Details Reveal?

Sunday

1. On Sunday, April 27, 1913, Frank told police officers, Mary Phagan arrived minutes after Miss Hall left his office at noon on April 26, 1913. Minutes after translates into 12:02 or 12:03, given that Miss Hall left at noon.

Monday

2. On Monday, April 28, 1913, Frank made a “statement” to Police Chief of Detectives Newport A. Lanford in front of numerous other police officers and a stenographer. Leo Frank said that Mary Phagan arrived at the second-floor office of the factory between “12:05 to 12:10, maybe 12:07” (as documented in State’s Exhibit B). Thus the arrival time increase by 3, 5, 8 minutes from 12:02 to 12:03 to 12:05 to 12:10, maybe 12:07. The “maybe” 12:07, some feel, indicates some kind of mental revelation as the exact time Phagan’s strangled body stopped struggling and breathing.

Inquest

3. At the coroner’s inquest jury of seven jurists (Coroner Donehoo plus six jurymen), Frank said Mary Phagan had arrived between about 12:10 and 12:15. Now the time moved past his two other statements by 8 to 13 minutes, presumably to be much closer to when “Lemmie Quinn arrived” in his office at 12:20 to 12:25 to make it seem like he didn’t have enough time to strangle Phagan.

Murder Trial (July 28 to August 26 1913), August 18, 1913 – Confession Question

4. On August 18, 1913, Leo Frank said Mary Phagan arrived between 12:12 to 12:17. More specifically, during his murder trial Frank said that Mary Phagan came into his office 10 to 15 minutes after Miss Hall left (Miss Hall testified she left immediately to a minute after noon) his office just after noon, putting Mary in his office in this changing version from as early as 12:10 through 12:12 to as late as 12:15 through 12:17 (assuming Miss Hall left at 12:00, 12:01, or 12:02).

Leo Frank Gave At Least Four Different Versions of Mary Phagan’s Arrival Time. Observers Want to Ask Leo Frank: So Which One Is It, Leo? And why Are All Four So Numerically Precise and So Disparate? Observers are asking why Leo keeps moving the time forward into the future? Knowing the answer is to likely distance himself from when the crime occurred. The Frankites over the last one hundred years give poor analyses of these vastly different times Leo Frank gave for obvious reasons.

The Big Fat Office Clock in Front of Leo Frank

The problem is that Leo Frank had a big clock right there in his office, which was an important part of his five years of employment at the pencil manufacturing plant, so people are only half-wondering why the time of arrival keeps changing when the clock was ticking so steadily and smoothly. Clock accuracy was only off by a minute or few, either way, one hundred years ago, adding another intriguing dimension to the time factor. Regardless, Frank knew the exact time Phagan arrived in his office, but he changed it four times.

The Bottom Line Concerning the Time: Frank repeatedly changed when Mary Phagan arrived and his whereabouts thereafter.

In What Way Did the Time Leo Frank Gave about Phagan Arriving Change?

Each time Frank gave a slightly different version of when Mary Phagan had arrived that inched forward by minutes. Sometimes he provided exact clock times, but other times he used more vague terms, putting the arrival time in terms in reference of when other people left (like when Hattie Hall and Alonzo Mann left) or arrived (Lemmie Quinn). Why did the time change completely every time Leo Frank was asked when Mary Phagan arrived? People are wondering why an accountant who logs the exact time, numbers, and money so precisely can’t seem to give an exact answer when a big clock was right in front of him at the time. Watson said Leo Frank repeatedly lied about his whereabouts and that of Mary Phagan because Frank’s statements were contradicted by others and himself (Watson, 1915).

The Ever Widening Time Spectrum

The ranges of time Leo Frank said Mary Phagan had arrived in his office and left according to the different statements he made varied from as early as 12:02, 12:03, 12:05, 12:07, 12:10, 12:12, 12:15 to 12:17. The problematic nature of this 15+ minute time range is that Leo Frank is unaccountable during this period in terms of there being a single witness to testify as to having seen Frank’s exact whereabouts.

The Hypothetical

If Mary Phagan had come after Monteen Stover at 12:11 or 12:12 (wouldn’t they bump into each other?) instead of the other way around, which really happened (Mary Phagan came before Monteen Stover), Leo Frank would put himself in the metal room bathroom alone without Mary Phagan. Thus Monteen Stover would wait in Leo Frank’s office while Frank was making #2 in the metal room toilet, because if he was making #1 instead, he would have been back within the five-minute time span that Monteen Stover waited for him in his office from 12:05 to 12:10. Applying the common sense test: In general, no man pees for five minutes or more. It would mean Frank was making #2, and he came from the toilet into his office when Mary arrived. This is what Leo Frank was postulating as his defense. He changed his testimony to account for Monteen Stover’s testimony.

Newfangled: Leo Frank Forgot Lemmie Quinn for One Week

Frank also seemed to have forgotten Lemmie Quinn for nearly a whole week after the murder, and because Frank waited so long to bring him up, it was considered suspicious and highly questionable as to whether it really happened. Both Leo Frank and Lemmie Quinn say that Quinn arrived between 12:20 to 12:25 at Frank’s office. He mentioned this at the coroner’s inquest and again at Leo Frank’s murder trial, but not before both of these events.

The coroner wanted to know why Leo Frank had waited so long to bring this new evidence forward, even after he remembered it before the coroner’s inquest. Why did he wait to bring it up at the coroner’s inquest and not tell the police sooner (Oney, 2003)?

Two employees would testify that they saw Lemmie Quinn leave the building area at around 11:30 to 11:45, putting Quinn’s testimony about coming to Frank’s office at 12:20 in question as possible perjury and a poorly concocted arrangement to make it seem like Frank did not have enough time to kill Mary Phagan.

Lemmie Quinn’s Affidavit Contradicted His Testimony

The affidavit in the Leo Frank brief of evidence by Lemmie Quinn makes it even more impossible that he might have come back to the office to visit Frank and ask about speaking with Schiff at the factory – on a holiday.

Schiff Never Missed Work for Five Years

Schiff, who was not supposed to even be at the factory that day, broke the whole Lemmie Quinn visit apart. Since Schiff prided himself on never missing a day of work in five years, why, on August 26, 1913, did he suddenly break this perfect record? He was never supposed to come to work on that holiday.

The whole Lemmie Quinn and Leo Frank 12:20 to 12:25 breaks down under the common sense test.

Frank Couldn’t Even Manufacture It with Lemmie Quinn at 12:20