Another in our series of new transcriptions of contemporary articles on the Leo Frank case.

Another in our series of new transcriptions of contemporary articles on the Leo Frank case.

Atlanta Constitution

Saturday, June 7th, 1913

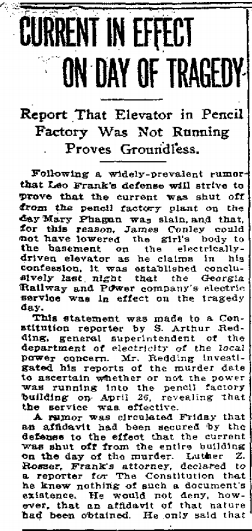

Report That Elevator in Pencil Factory Was Not Running Proves Groundless.

Following a widely-prevalent rumor that Leo Frank’s defense will strive to prove that the current was shut off from the pencil factory plant on the day Mary Phagan was slain, and that, for this reason, James Conley could not have lowered the girl’s body to the basement on the electrically-driven elevator as he claims in his confession, it was established conclusively last night that the Georgia Railway and Power company’s electric service was in effect on the tragedy day.

This statement was made to a Constitution reporter by S. Arthur Redding, general superintendent of the department of electricity of the local power concern. Mr. Redding investigated his reports of the murder date to ascertain whether or not the power was running into the pencil factory building on April 26, revealing that the service was effective.

A rumor was circulated Friday that an affidavit had been secured by the defense to the effect that the current was shut off from the entire building on the day of the murder. Luther Z. Rosser, Frank’s attorney, declared to a reporter for The Constitution that he knew nothing of such a document’s existence. He would not deny, however, that an affidavit of that nature had been obtained. He only said that word of its existence was “news to him.”

Shut Off From Inside.

Superintendent Redding said it was probable that the current was shut off from the inside of the plant, as is usual in all factories employing electric power. In this case, however, he declared that to turn on the power required only the plugging of an individual switch, which would have been a fixture of the plant’s not the power company’s.

Negro Sticks to Story.

Conley, when informed of the rumored affidavit, strongly maintained, the detectives who questioned him say, that he did operate the elevator to carry down the girl’s body, and that Frank drove it on the return trip. Furthermore, he is said to have declared the power company was not accustomed to shutting down the current on holidays.

Another startling rumor gained headway Friday in which A. S. Colyar, the sensational figure in the dictagraph charges, was said to have announced his possession of a sworn confession from the negro Conley, and that he had told Sheriff Mangum of it. The rumor had it that Conley had admitted to Colyar that he murdered the girl.

Chief Lanford branded the story as a total falsehood. He had heard it on Thursday night, he said, and immediately had ordered Conley brought to his office for examination. The negro, says the chief, told him emphatically that he had never intimated anything relative to having slain the girl, and that he made no sworn statements other than those in hands of the detectives.

Furthermore, the chief declares, Conley avowed he had never seen or heard of Colyar except through what he had read of him in the newspapers. Also, in a telephone conversation with Colyar, Lanford declares Colyar denied having made the reported statement, and said that he had never even seen the negro sweeper, much less talked with him.

Has Negro Cook Disappeared?

The report prevailed at police headquarters Friday that Minola McKnight, the servant girl in the Frank household, had mysteriously disappeared, and that no trace of her could be found. Investigation at the Frank home, 68 East Georgia avenue, revealed, it is said, that she was there no longer. Neither is she reported to be at her home on Pulliam street.

Her attorney, George Gordon, refuses to talk of his client or of her whereabouts. Neither will he speak of his connection with the case. He has admitted, heretofore, however, that he is counsel for the woman who recently made such a startling affidavit which she denied almost twenty-four hours after it had been in the hands of the solicitor general.

* * *