Another in our series of new transcriptions of contemporary articles on the Leo Frank case.

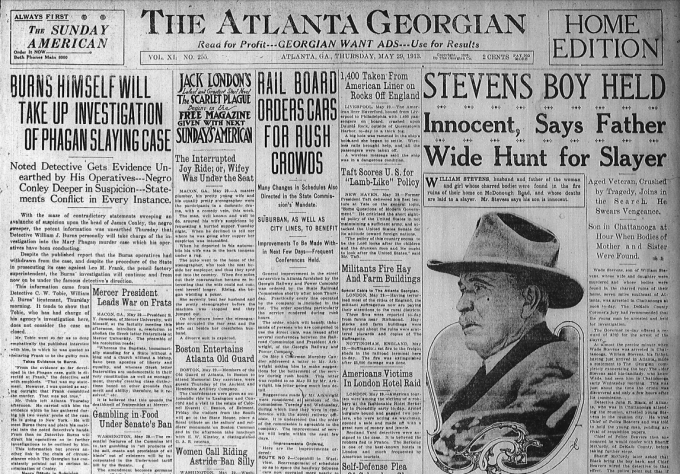

Atlanta Georgian

Thursday, May 29th, 1913

All Evidence Gathered by His Operatives Sent to the Noted Detective.

James Conley, the negro sweeper at the National Pencil Factory who has turned suspicion on himself with a maze of contradictory statements, was put through a gruelling third degree examination at police headquarters this afternoon. Pinkerton Detective Harry Scott said as the grilling began before Chief Beavers and Chief Lanford that he expected to glean important information. Scott had interviewed factory employees and was convinced that there were many things to be cleared up before the negro’s second affidavit, on which the police rely so much, could be accepted.

With the maze of contradictory statements sweeping an avalanche of suspicion upon the head of James Conley, the negro sweeper, the potent information was unearthed Thursday that Detective William J. Burns personally will take charge of the investigation into the Mary Phagan murder case which his operatives have been conducting.

Despite the published report that Burns operatives had withdrawn from the case, and despite the procedure of the State in prosecuting its case against Leo M. Frank, the pencil factory superintendent, the Burns investigation will continue and from now on be under the famous detective’s direction.

This information came from Detective C. W. Tobie, William J. Burns’ lieutenant, Thursday morning. It tends to show that Tobie, who has had charge of his agency’s investigation here, does not consider the case as closed.

Mr. Tobie went so far as to deny emphatically the published interview with him, in which he was quoted as declaring Frank to be the guilty man.

Takes Evidence to Burns.

“From the evidence so far developed in the Phagan case, guilt is directed at Frank,” the detective said with emphasis. “That was my statement. However, I was quoted as saying outright that Frank committed the murder. That was not true.”

Mr. Tobie left Atlanta Thursday afternoon. He carried with him the evidence which he has gathered during his two weeks’ probe of the case. He is going to New York. He will meet Burns there and place his material into the noted detective’s hands. From then on Detective Burns will direct his operatives as to further investigations to be outlined by him.

This information but proves another link in the chain of circumstances which The Georgian has consistently pointed out in serious incrimination of Conley.

Negro Deeper in Suspicion.

With each cross-examination of the negro by the police in their attempts to secure more evidence against Frank, Conley has only insnared himself in guilt. His admitted falsehoods in former affidavits tending to throw the blame to Frank in connection with the “murder” notes have been accentuated as incriminating by the unqualified declarations of employees at the pencil factory that Conley is the guilty man.

Three responsible officials of the plant have outlined plausible theories as to how the negro could have committed the crime. These men, Herbert G. Schiff, who is assistant superintendent; E. F. Holloway, timekeeper, and N. V. Darley, general foreman, are acquainted with Conley. Upon their knowledge of him and the opportunity offered for accomplishing the murder they base their statements that he is guilty. They have proven beyond a doubt that Conley was in the factory for several hours on the day of the murder, and connecting with this the negro’s contradictory statements as to his whereabouts they have compiled a most laudable explanation of how he killed the Phagan girl.

The detective still held firmly to their theory that the negro was the most important witness against Leo M. Frank, in the face of the contradictory stories and lies in which he had been trapped.

They were strongly disposed to give full credence to Conley’s second affidavit, although the negro’s sudden anxiety to talk after three weeks of silence and the maze of falsehood in which he was at once involved served suddenly to shift responsibility for Mary Phagan’s death from Leo Frank to the sullen black man, in the judgment of many who have been following the evidence closely.

Chief Lanford and Detective Harry Scott, of the Pinkertons, announced Thursday morning, however, that they regarded the second affidavit of Conley as the final and conclusive piece of evidence needed in preparing a case against Frank.

Rejected First Affidavit.

Others who have weighed the evidence carefully declare there are many more significant indications that Conley was the slayer than there are reasons to believe that Frank is guilty.

The detectives rejected the first affidavit of Conley, in which he said Frank dictated Friday the notes that were found by the body of the slain girl Sunday morning on the ground that it was absurd and unbelievable to hold the theory that the murder was premeditated.

Yet they accept the second affidavit, which indicates identically the same thing, in that Frank met Conley at Nelson and Forsyth Streets before 11 o’clock Saturday morning, April 26, before the crime was committed, and told the negro to wait for him, later taking Conley to the factory with him, where Conley says that he wrote the notes at Frank’s direction.

The negro in his second affidavit suggests no other motive that could have impelled Frank to ask him to come to the factory shortly before noon on Saturday. Conley says that Frank told him to wait secreted on the first floor until he heard a whistle. When he heard the whistle he says he went upstairs and Frank dictated the notes.

Why Many Suspect Conley.

All of this is inescapably suggestive of premeditation on the part of Frank, if Conley’s story is to be believed, but the theory of premeditation has been scoffed at by everyone, including Chief Lanford and Harry Scott.

In fact, it never seriously was considered by anyone, say those who are inclined to believe the evidence against Conley greatly outweighs that against Frank. The assertion is freely made that it would be far easier to convict Conley, if the police were so disposed, than it will be to convict Frank. Here are a few reasons advanced:

When the factory superintendent was permitted to go before the Coroner’s jury by his attorney, he answered all the questions in a straight-forward, unwavering manner, never once being trapped in a lie or misstatement.

In marked contrast is the conduct of Conley ever since his arrest at the time of the inquest three weeks ago. When discovered at the factory, he was washing a shirt which he sought to hide from the person who had found him out.

He was taken into custody and gave his address as 92 Tattnall Street. Investigation disclosed that Conley was lying and that he had not lived on Tattnall Street for months, his actual residence being 172 Rhodes Street.

He was asked to write, and he told the officers he could not write a word. He refused to be inveigled into making an attempt at handwriting of any sort. He would not put a pencil to paper that the detectives might get a specimen of his penmanship. For a long time they believed he was so ignorant he could not write his own name. Then they found some leases he had signed for watches and knew that he had been lying again.

Just as the Grand Jury was about to sit and it appeared likely that Frank would be indicted, the negro broke his silence for the first time. He told the detectives that it was he who had written the notes, but that he had written them at Frank’s dictation on Friday, April 25. Frank had approached him in an aisle at the factory and had asked him to come into the office, he said. He remembered that it was four minutes before 1 o’clock.

That he had been at the factory Saturday he denied emphatically. Between 10 o’clock in the forenoon and 2 o’clock in the afternoon he had been on Peters Street, according to his story.

The detectives ridiculed his story and continued examining. Gradually he broke down under their questioning, and it was established that he had been lying again and that he actually had been in the factory Saturday, presumably at the very time the girl was murdered. This was the first time his presence in the factory on Saturday had been known.

He had kept it a most profound secret up to the time it was gouged out of him by the detectives. He weakened further and admitted that he had been hiding down on the first floor as persons went in and out.

He described practically every person that entered or left the factory between 12 and 1 o’clock. But he declared that he did not see Mary Phagan when she came in the building. Out of all who entered or left, the murdered girl and Lemmie Quinn appear to be the only ones he missed seeing, according to his story.

He explained this by saying that he must have fallen asleep for a little while. He saw Miss Corinthia Hall and Mrs. Freeman leave a few minutes before 1 o’clock, but did not see Mary Phagan enter about five minutes after the hour. Neither did he see Lemmie Quinn, who is said to have been at the factory about 12:15.

If the negro’s final affidavit is taken as nearer the probable truth than his first, those who are acquainted with Frank are of the opinion that there are still most important questions to be answered convincingly. They are these, assuming Frank is guilty:

“Why should a man of Frank’s intelligence—a man who is highly educated and who has won a position of responsibility—virtually make a confidant of another man, especially an ignorant negro, easily broken down by the third degree of the police station?”

“Why should a man of sense, if he wished to keep his crime undiscovered, proclaim it to the negro, in his office by the question: ‘Why should I hang?’”

“Why should he approach this negro more than an hour before this crime was committed?”

* * *

Atlanta Georgian, May 29th 1913, “Burns Joins in Hunt for Phagan Slayer,” Leo Frank case newspaper article series (Original PDF)